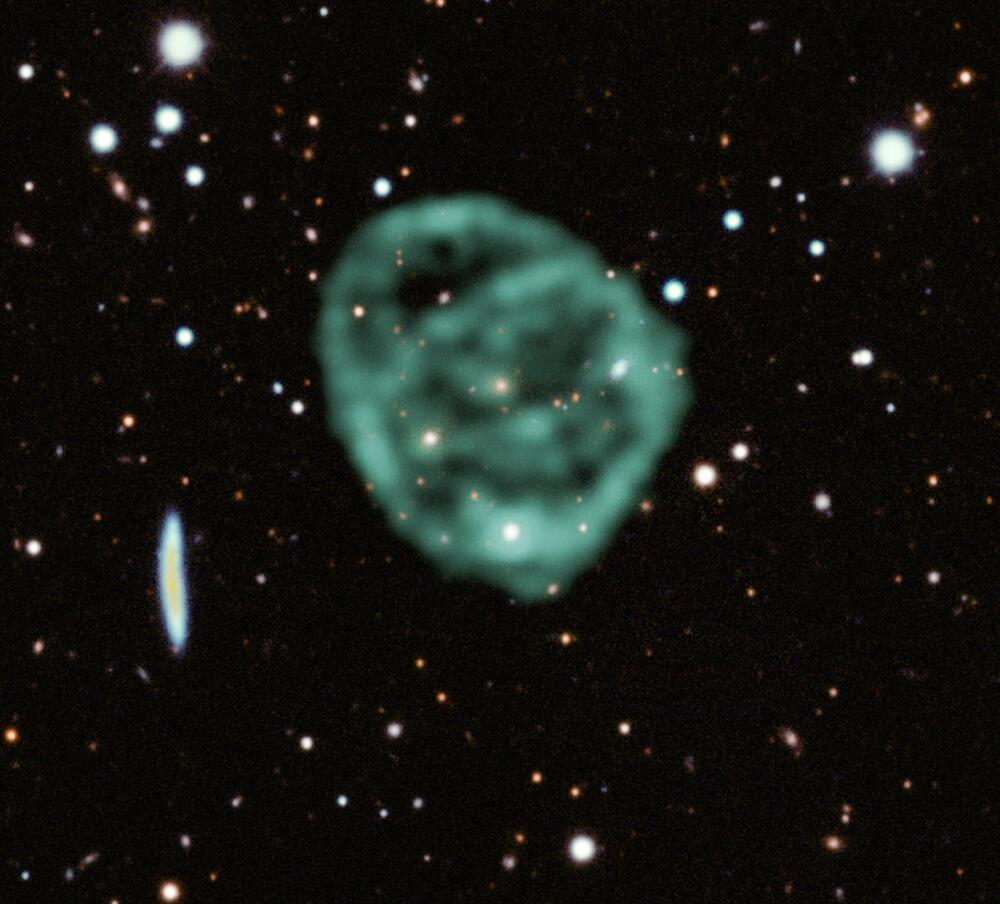

Astronomy’s newest mystery objects—odd radio circles, or ORCs—have been pulled into sharp focus by an international team of astronomers using the world’s most capable radio telescopes.

When first revealed in 2020 by the ASKAP radio telescope, owned and operated by Australia’s national science agency CSIRO, odd radio circles quickly became objects of fascination. Theories on what causes them ranged from galactic shockwaves to the throats of wormholes.

A new detailed image, captured by the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory’s MeerKAT radio telescope and published today in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, is providing researchers with more information to help narrow down those theories.