How can Einstein’s theory of gravity be unified with quantum mechanics? It is a challenge that could give us deep insights into phenomena such as black holes and the birth of the universe. Now, a new article in Nature Communications, written by researchers from Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, and MIT, U.S., presents results that cast new light on important challenges in understanding quantum gravity.

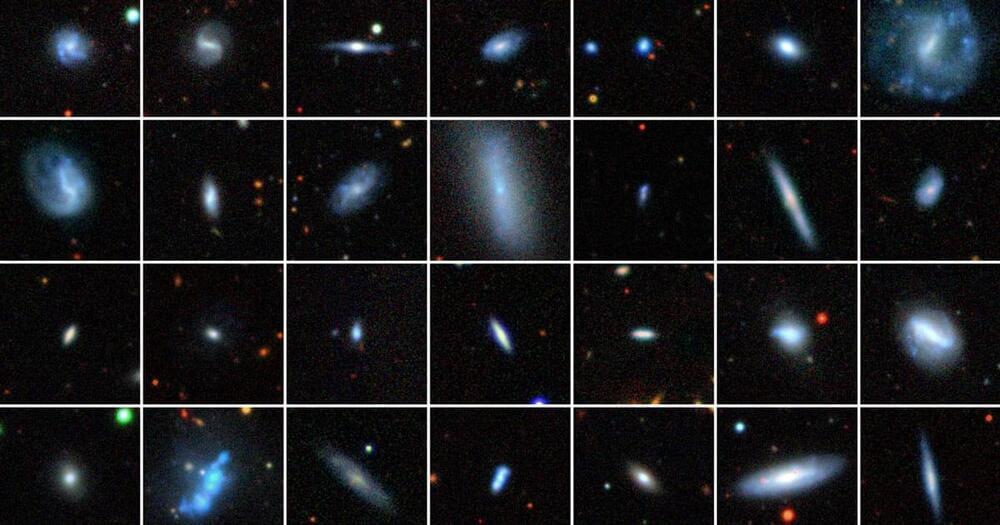

A grand challenge in modern theoretical physics is to find a “unified theory” that can describe all the laws of nature within a single framework—connecting Einstein’s general theory of relativity, which describes the universe on a large scale, and quantum mechanics, which describes our world at the atomic level. Such a theory of “quantum gravity” would include both a macroscopic and microscopic description of nature.

“We strive to understand the laws of nature and the language in which these are written is mathematics. When we seek answers to questions in physics, we are often led to new discoveries in mathematics too. This interaction is particularly prominent in the search for quantum gravity—where it is extremely difficult to perform experiments,” explains Daniel Persson, Professor at the Department of Mathematical Sciences at Chalmers university of technology.