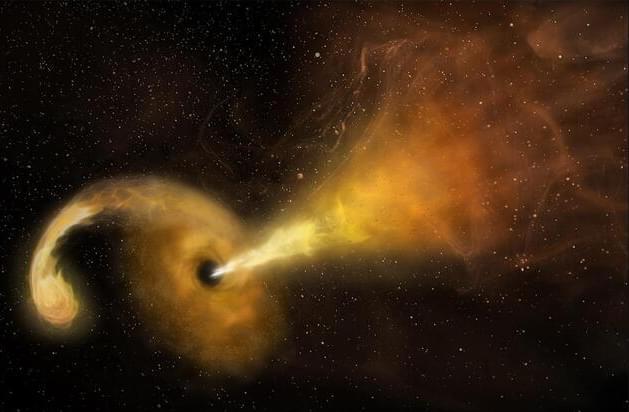

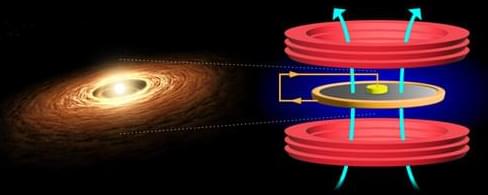

Researchers may have solved Professor Stephen Hawking’s famous black hole paradox—a mystery that has puzzled scientists for almost half a century.

According to two new studies, something called “quantum hair” is the answer to the problem.

In the first paper, published in the journal Physical Review Letters, researchers demonstrated that black holes are more complex than originally thought and have gravitational fields that hold information about how they were formed.