Recent theoretical and observational results have revealed new secrets about these shadowy objects, with deep implications for more than just black holes themselves.

Recent theoretical and observational results have revealed new secrets about these shadowy objects, with deep implications for more than just black holes themselves.

In late May, a collaborative study, led by Kailash Suhu, was published claiming that they had managed to identify the first ever isolated black hole, identified by shorthand as OB11046. While by itself, this discovery presents no new information with regards to their nature, it highlights the staggering progress we’ve made in recent years in detecting these bodies.

Previously, black hole detection was very much limited by the fact that they do not emit, nor reflect any detectable electromagnetic radiation. As such, astronomers were only able to infer their presence via two mechanisms.

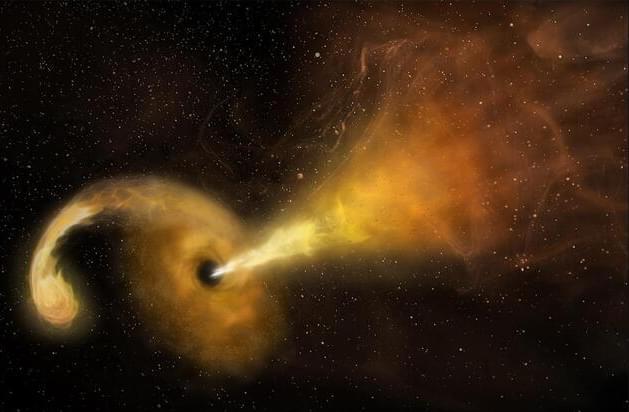

The first is by tracking the orbits of nearby celestial bodies and observe whether their motion can be modelled by the forces experienced by their neighbours. Any unusual motion can usually be explained by a nearby black hole contributions. The second requires the black hole to form an accretion disk. As matter is caught in the intense gravitational field, it orbits the black hole and is accelerated to intense velocities, causing the material to emit certain wavelengths of high energy electromagnetic radiation, such as x-rays.

The first GWs were detected in 2015 by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO), when two black holes about 1.3 billion light-years away slammed into each other. LIGO consists of two interferometers — one in Louisiana, one in Washington state — which are L-shaped vacuum tunnels about 2.5 miles long on each side. A laser is shot from the crux of the L to mirrors at the end of each side, and if one of those laser beams arrives slightly late, the tardy beam is recorded by the detector. The detectors are sensitive enough to pick up nearby noises on Earth as well, such as passing trucks and falling trees. These events can mask or mimic gravitational-wave signals, so having two detectors far apart helps scientists distinguish real GW vibrations from false alarms.

The actual detector that spotted the first gravitational wave is now in the Nobel Prize Museum in Stockholm, Sweden, as the 2017 Nobel Prize in physics was awarded for this discovery. But LIGO didn’t stop there: A few months later, in collaboration with the newly completed Virgo interferometer in Italy, LIGO detected another gravitational wave event — this time produced by colliding neutron stars. The discovery also corresponded with a short gamma-ray burst and subsequent discovery of the merger site with optical telescopes. Within days of that momentous discovery, however, LIGO went offline for scheduled upgrades.

The machine functions in curved spaces defying the laws of Earth.

The robot recreates the same environment found around black holes. It does so by moving in a curved space. It could one day allow us to further study black holes.

There is one constant on Earth and that is that when humans, animals, and machines move, they always push against something, whether it’s the ground, air, or water. This fact consists of the law of conservation momentum and was up to now undisputed.

Curved spaces provide new principles However, new research from the Georgia Institute of Technology has come along to showcase the opposite — when bodies exist in curved spaces, they can move without pushing against something. The new study was led by Zeb Rocklin, assistant professor in the School of Physics at Georgia Tech, and it saw the engineering of “a robot confined to a spherical surface with unprecedented levels of isolation from its environment, so that these curvature-induced effects would predominate,” according to a statement by the institution published on Monday.

Full Story:

The new machine defies the laws of physics to function in curved spaces.

Circa 2019 This could lead to reactors that last nearly forever and spaceships that do not run out of fuel.

Deep under an Italian mountainside, a giant detector filled with tons of liquid xenon has been looking for dark matter—particles of a mysterious substance whose effects we can see in the universe, but which no one has ever directly observed. Along the way, however, the detector caught another scientific unicorn: the decay of atoms of xenon-124—the rarest process ever observed in the universe.

The results from the XENON1T experiment, co-authored by University of Chicago scientists and published April 25 in the journal Nature, document the longest half-life in the universe—and may be able to help scientists hunt for another mysterious process that is one of particle physics’ great mysteries.

Not all atoms are stable. Depending on their makeup, some will stabilize themselves by releasing subatomic particles and turning into an atom of a different element—a process called radioactive decay.

Researchers may have solved Professor Stephen Hawking’s famous black hole paradox—a mystery that has puzzled scientists for almost half a century.

According to two new studies, something called “quantum hair” is the answer to the problem.

In the first paper, published in the journal Physical Review Letters, researchers demonstrated that black holes are more complex than originally thought and have gravitational fields that hold information about how they were formed.

Circa 2022

We report on two extensions of the traditional analysis of low-dimensional structures in terms of low-dimensional quantum mechanics. On one hand, we discuss the impact of thermodynamics in one or two dimensions on the behavior of fermions in low-dimensional systems. On the other hand, we use both quantum wells and interfaces with different effective electron or hole mass to study the question when charge carriers in interfaces or layers exhibit two-dimensional or three-dimensional behavior.

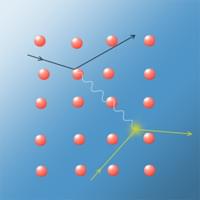

The Migdal effect inside detectors provides a new possibility of probing the sub-GeV dark matter (DM) particles. While there has been well-established methods treating the Migdal effect in isolated atoms, a coherent and complete description of the valence electrons in a semiconductor is still absent. The bremstrahlunglike approach is a promising attempt, but it turns invalid for DM masses below a few tens of MeV. In this paper, we lay out a framework where phonon is chosen as an effective degree of freedom to describe the Migdal effect in semiconductors. In this picture, a valence electron is excited to the conduction state via exchange of a virtual phonon, accompanied by a multiphonon process triggered by an incident DM particle. Under the incoherent approximation, it turns out that this approach can effectively push the sensitivities of the semiconductor targets further down to the MeV DM mass region.

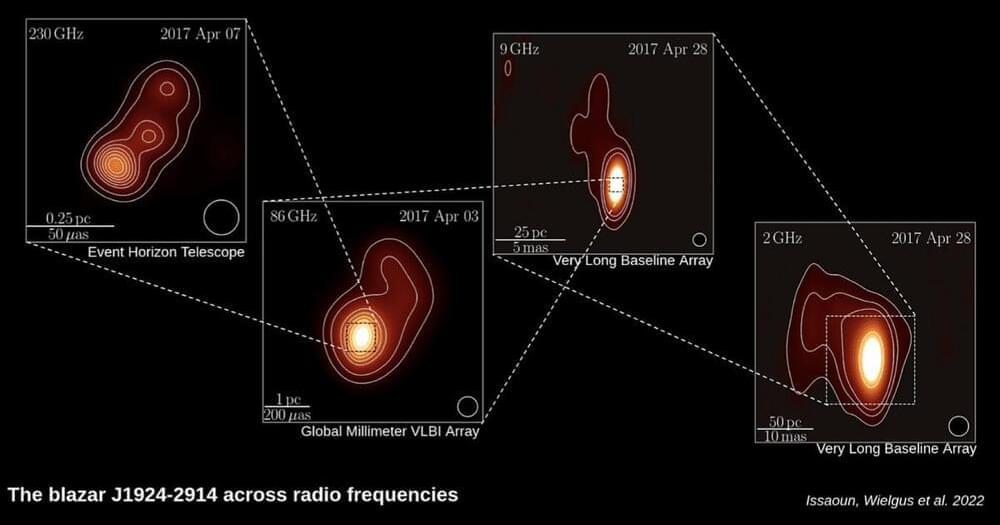

Having a virtual telescope the size of Earth continues to pay off.

The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) has released new observations that are once again at the cutting edge of science. The team that gave us the first image of our very own supermassive black hole has now revealed the most detailed radio image of a blazer, J1924-2914.

A blazar, not to be confused with a bright dinner jacket, is an active supermassive black hole whose jet is being shot towards us. The EHT has delivered observations with unprecedented angular resolution: it can resolve structures within 3 light-years of the black hole. Not bad given the host galaxy is located over 4 billion light-years from us.

Published in The Astrophysical Journal, the achievement is based on data conducted during the original observation campaign in April 2017 that gave us the first-ever image of a black hole. The team studied structures just a few light-years in size to hundreds of light-years wide thanks to the combination of multiple observatories around the world acting as one Earth-sized telescope.

Capturing details of faraway members of our universe is an understandably complicated affair, but translating these details into the stunning space images that we see from space agencies around the world is equally difficult. It is here that supercomputers step in, helping process the massive amounts of data that are captured by terrestrial and space telescopes. On August 11, that is exactly what Australia’s upcoming supercomputer, called Setonix, helped achieve.