It’s what we expected, but now it’s confirmed.

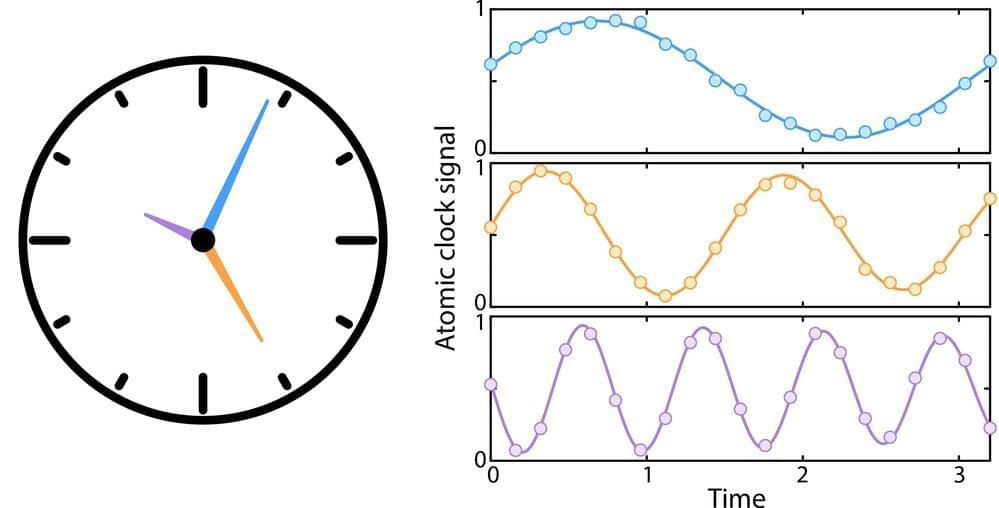

Atomic clocks are a class of clocks that leverage resonance frequencies of atoms to keep time with high precision. While these clocks have become increasingly advanced and accurate over the years, existing versions might not best utilize the resources they rely on to keep time.

Researchers at the California Institute of Technology recently explored the possibility of using quantum computing techniques to further improve the performance of atomic clocks. Their paper, published in Nature Physics, introduces a new scheme that enables the simultaneous use of multiple atomic clocks to keep time with even greater precision.

“Atomic clocks are decades old, but their performance improves every year,” Adam Shaw, co-author of the paper, told Phys.org.

Devices that exhibit electrical resonance, have a nominally infinite number of quantum levels.

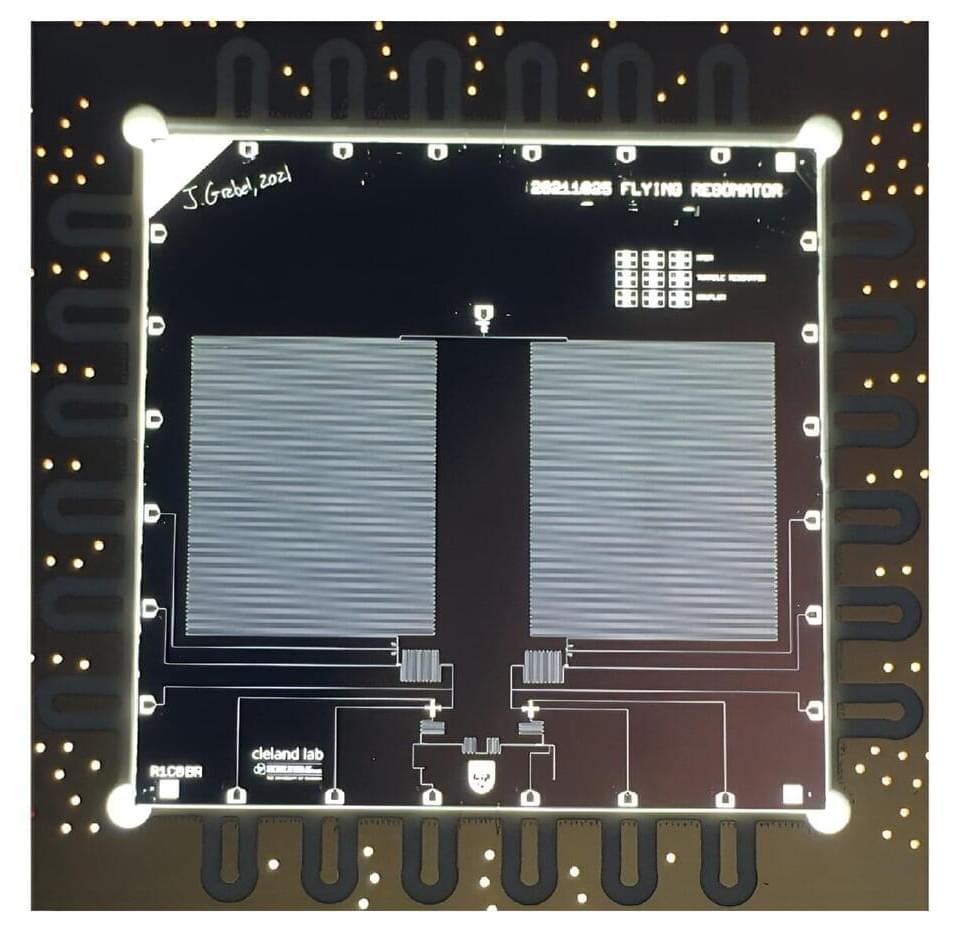

Over the past few decades, quantum physicists and engineers have been trying to develop new, reliable quantum communication systems. These systems could ultimately serve as a testbed to evaluate and advance communication protocols.

Researchers at the University of Chicago recently introduced a new quantum communication testbed with remote superconducting nodes and demonstrated bidirectional multiphoton communication on this testbed. Their paper, published in Physical Review Letters, could open a new route towards realizing the efficient communication of complex quantum states in superconducting circuits.

“We are developing superconducting qubits for modular quantum computing and as a quantum communication testbed,” Andrew Cleland, co-author of the paper, told Phys.org. “Both rely on being able to communicate quantum states coherently between qubit ‘nodes’ that are connected to one another with a sparse communication network, typically a single physical transmission line.”

Apple is known for its “One More Thing” moments, unveiling a new product to revolutionize the industry. The Apple Vision Pro, the company’s first augmented reality headset, was supposed to be one of those products. But according to a recent report, it might take Apple a few more years and a few more versions to achieve its vision.

A revolutionary product that will become affordable eventually

The Apple Vision Pro, launched in late 2023, is a sleek and futuristic device that lets users interact with digital content overlayed in the real world. It runs on visionOS, a new operating system designed for immersive experiences. It also comes with a hefty price tag of $3,500, making it a niche product for early adopters and enthusiasts.

That’ll be a nice tipping point. Now we need to depend less on Taiwan for chip making or move it to the USA and maybe China will lose interest a bit.

The US could soon become a world leader in rare earth minerals after over two billion metric tons were found in Wyoming.

The discovery could mean America taking over China, whose supplies stand at 44 million metric tons.

According to American Rare Earths Inc, the discovery ‘exceeded [their] wildest dreams’ having only drilled around a quarter of the project.

Recent research conducted at Hebrew University has uncovered a previously unknown connection between light and magnetism. This finding paves the way for the development of ultra-fast memory technologies controlled by light, as well as pioneering sensors capable of detecting the magnetic components of light. This advancement is anticipated to transform data storage practices and the fabrication of devices across multiple sectors.

Professor Amir Capua, head of the Spintronics Lab within the Institute of Applied Physics and Electrical Engineering at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, announced a pivotal breakthrough in the realm of light-magnetism interactions. The team’s unexpected discovery reveals a mechanism wherein an optical laser beam controls the magnetic state in solids, promising tangible applications in various industries.

GHZ states are crucial for pushing the boundaries of quantum physics and enhancing quantum computing and communication technologies. However, they become increasingly unstable as more qubits are entangled, with past experiments demonstrating the challenges of preserving their unique properties amidst minor disturbances. By employing a discrete time crystal, the team was able to construct a “safe house” to protect the GHZ state, achieving a less fragile configuration of 36 qubits, compared to the previously unstable larger state that included up to 60 qubits.

The application of microwave pulses to the qubits not only induced their quantum properties to oscillate and form a time crystal but also minimized disturbances that would typically disrupt the GHZ state. This could mark the first practical use of a discrete time crystal, according to Biao Huang, Kavli Institute for Theoretical Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Scientists have previously established that light can be slowed down in certain scenarios, and a new study demonstrates a method for achieving it that promises to be one of the most useful approaches yet.

The researchers behind the breakthrough, from Guangxi University and the Chinese Academy of Sciences in China, say that their method could benefit computing and optical communication.

Light zipping through the emptiness of space moves at one speed and one speed only — 299,792 kilometers (about 186,000 miles) per second. Yet if you throw a mess of electromagnetic fields into its path, such as those surrounding ordinary matter, that extraordinary velocity starts to slow.

It’s “Little Shop of Horrors” meets “Terminator.”

A team of scientists successfully took control over a Venus Flytrap, a type of cultivated carnivorous plant, by implanting a tiny microchip in it.

This “artificial neutron” was able to force the plants to open and close — conventionally a way for them to devour its prey — mimicking the brain’s methods of processing and transferring information.