Working with multi-dimensional entities could make calculations more efficient and reduce errors.

A new study published in Frontiers in Computer Science investigated if placing smartphones just out of our reach while we’re at work influenced device use for activities not related to work.

“The study shows that putting the smartphone away may not be sufficient to reduce disruption and procrastination, or increase focus,” said the paper’s author Dr. Maxi Heitmayer, a researcher at the London School of Economics. “The problem is not rooted within the device itself, but in the habits and routines that we have developed with our devices.”

A quantum state of light was successfully teleported through more than 30 kilometers (around 18 miles) of fiber optic cable amid a torrent of internet traffic – a feat of engineering once considered impossible.

The impressive demonstration by researchers in the US in 2024 may not help you beam to work to beat the morning traffic, or download your favourite cat videos faster.

However, the ability to teleport quantum states through existing infrastructure represents a monumental step towards achieving a quantum-connected computing network, enhanced encryption, or powerful new methods of sensing.

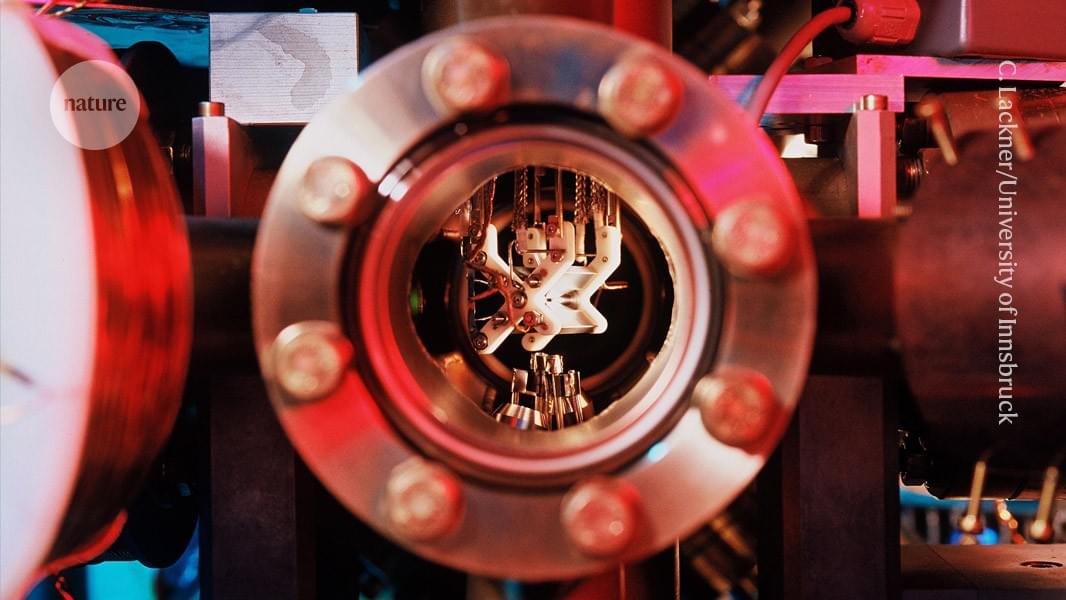

In a new study published by researchers at quantum computing company Quantinuum and collaborators from Caltech, Fermioniq, EPFL, and the Technical University of Munich, scientists have used Quantinuum’s powerful quantum computer, H2, to simulate a notoriously difficult system—quantum magnetism —in a way that pushes beyond what classical computers can reliably achieve.

“Digital quantum computers are much more flexible/universal, but we have paid for that flexibility with many technical challenges,” Dr. Michael Foss-Feig of Quantinuum and the paper’s lead author told the Debrief.

“This paper is an indication that we are finally moving these more flexible/universal machines into the realm of practical (and scientifically illuminating) quantum simulation,” Foss-Feig said.

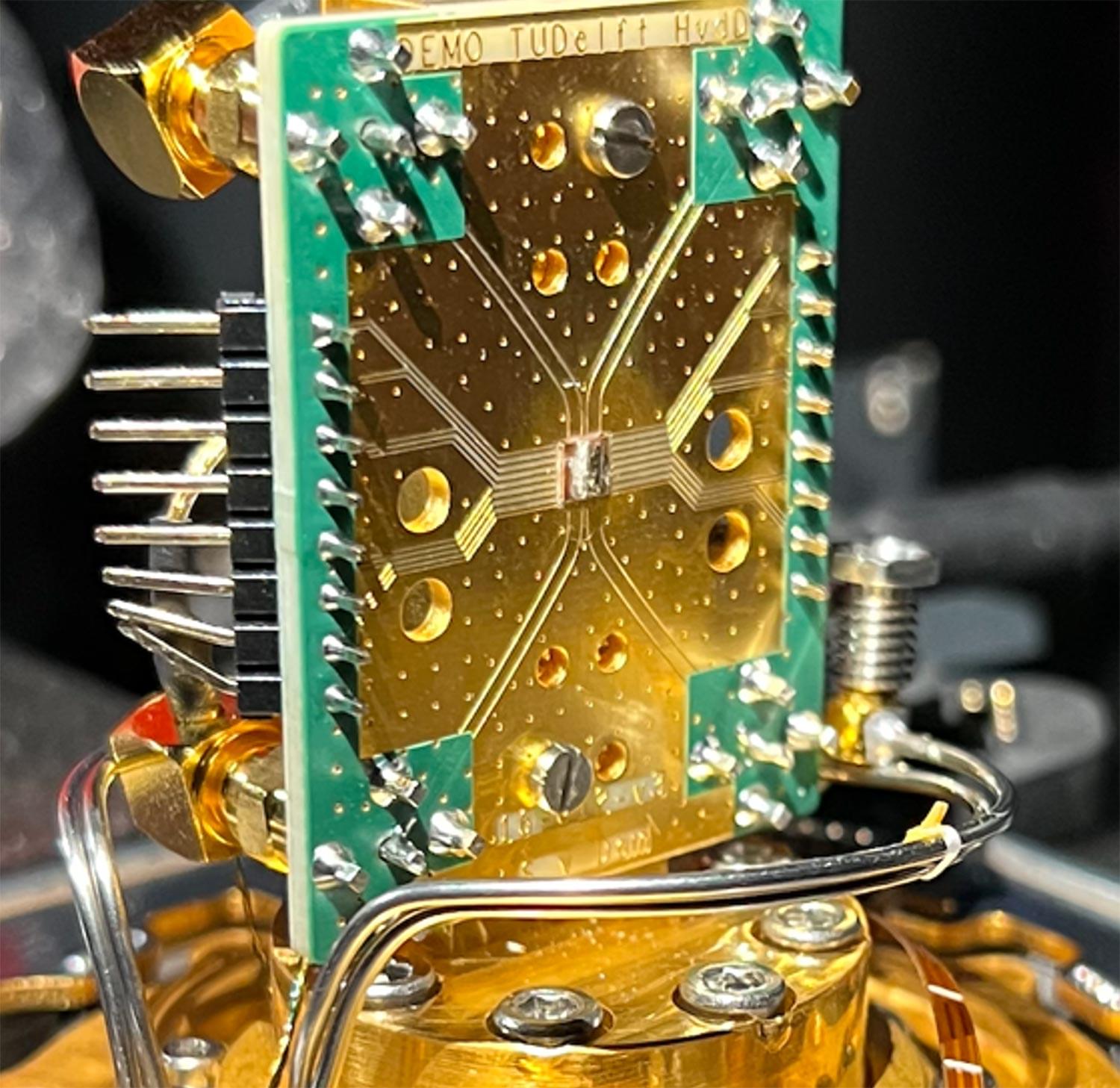

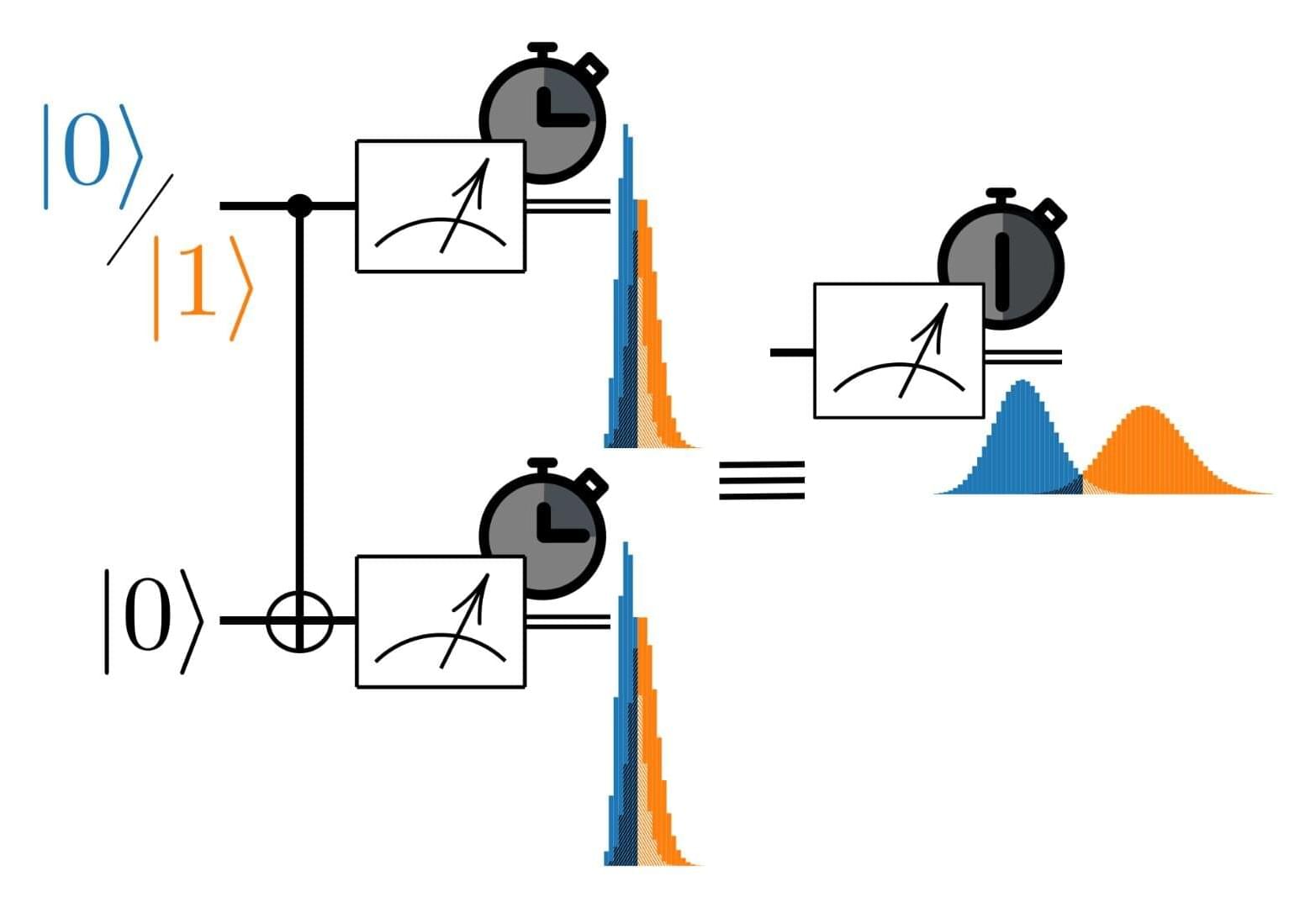

In an attempt to speed up quantum measurements, a new Physical Review Letters study proposes a space-time trade-off scheme that could be highly beneficial for quantum computing applications.

Quantum computing has several challenges, including error rates, qubit stability, and scalability beyond a few qubits. However, one of the lesser-known challenges quantum computing faces is the fidelity and speed of quantum measurements.

The researchers of the study address this challenge by using additional or ancillary qubits to significantly reduce measurement time while maintaining or improving the quality of measurements.

More than 80 years ago, Erwin Schrödinger, a theoretical physicist steeped in the philosophy of Schopenhauer and the Upanishads, delivered a series of public lectures at Trinity College, Dublin, which eventually came to be published in 1944 under the title “What is Life?”

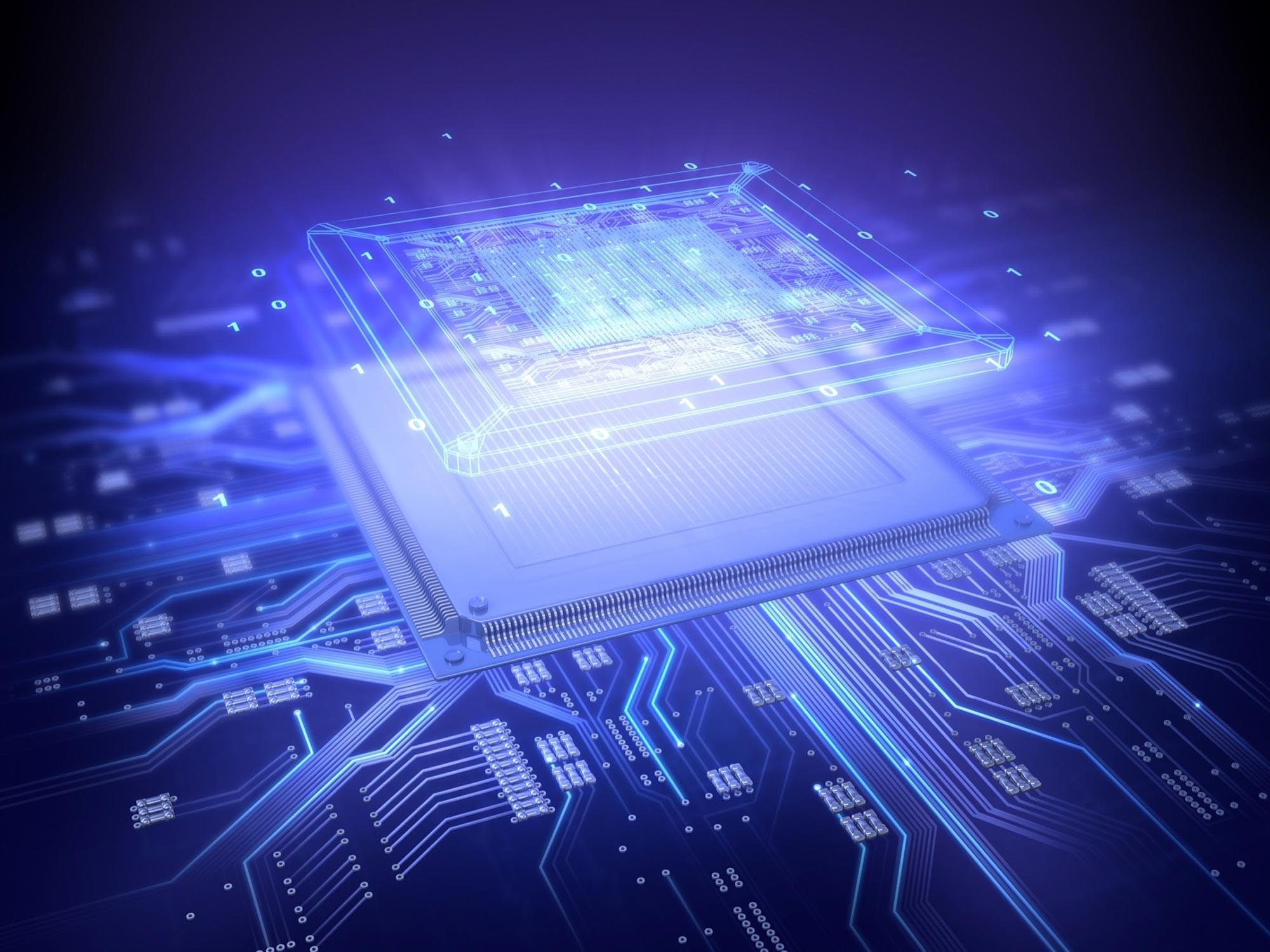

Now, in the 2025 International Year of Quantum Science and Technology, Philip Kurian, a theoretical physicist and founding director of the Quantum Biology Laboratory (QBL) at Howard University in Washington, D.C., has used the laws of quantum mechanics, which Schrödinger postulated, and the QBL’s discovery of cytoskeletal filaments exhibiting quantum optical features, to set a drastically revised upper bound on the computational capacity of carbon-based life in the entire history of Earth.

Published in Science Advances, Kurian’s latest work conjectures a relationship between this information-processing limit and that of all matter in the observable universe.