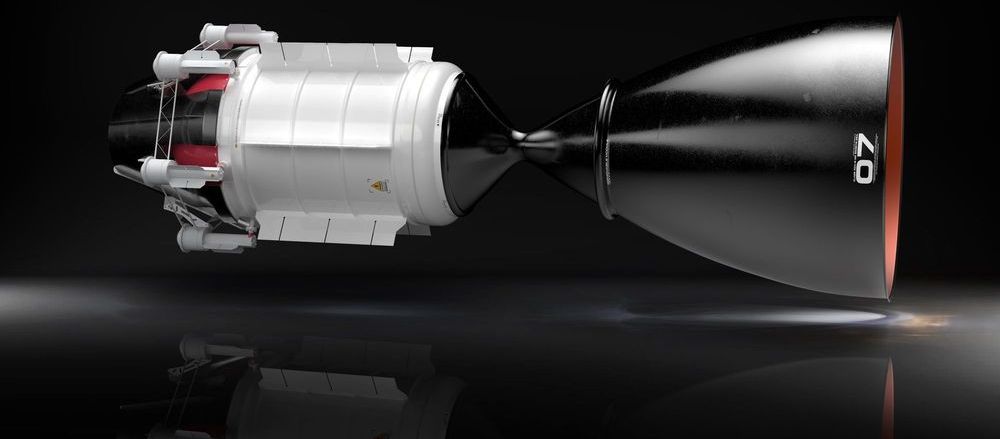

Seattle-based Ultra Safe Nuclear Technologies (USNC-Tech) has developed a concept for a new Nuclear Thermal Propulsion (NTP) engine and delivered it to NASA. Claimed to be safer and more reliable than previous NTP designs and with far greater efficiency than a chemical rocket, the concept could help realize the goal of using nuclear propulsion to revolutionize deep space travel, reducing Earth-Mars travel time to just three months.

Because chemical rockets are already near their theoretical limits and electric space propulsion systems have such low thrust, rocket engineers continue to seek ways to build more efficient, more powerful engines using some variant of nuclear energy. If properly designed, such nuclear rockets could have several times the efficiency of the chemical variety. The problem is to produce a nuclear reactor that is light enough and safe enough for use outside the Earth’s atmosphere – especially if the spacecraft is carrying a crew.

According to Dr. Michael Eades, principal engineer at USNC-Tech, the new concept engine is more reliable than previous NTP designs and can produce twice the specific impulse of a chemical rocket. Specific impulse is a measure of a rocket’s efficiency.