Lithium Ion-based batteries are among the most effective and widely used battery technologies. However, the batteries’ electrolytes mainly contain organic carbonated solvents, which are considered highly flammable with a narrow temperature window. To ensure that they don’t catch fire while operating at extreme temperatures, engineers must design safer electrolytes that are not only non-flammable, but also able to operate at a wide temperature range.

Researchers in the University of California San Diego’s Shirley Meng group and at the Army Research Laboratory have recently developed new liquefied gas electrolytes that could be used to produce lithium-metal batteries that can operate safely from-60 to 55 o C. These electrolytes have a unique structure, outlined in a paper published in Nature Energy, which make them capable of extinguishing fire.

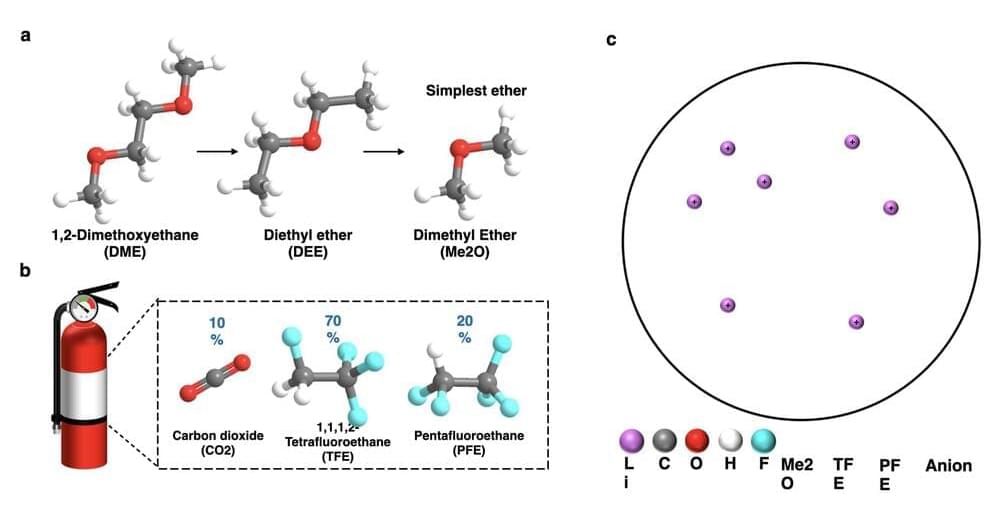

“The liquefied gas electrolyte (LGE) was firstly conceptualized by our research group in a paper published in Science in 2017 and has been developed over five years,” Yijie Yin, one of the researchers who are working in this field from Prof. Meng’s lab, told TechXplore. “It consists of a variety of fluorocarbon gases, that when put under pressure, liquefies to form a chemically stable, low-freezing point, low-cost electrolyte.”