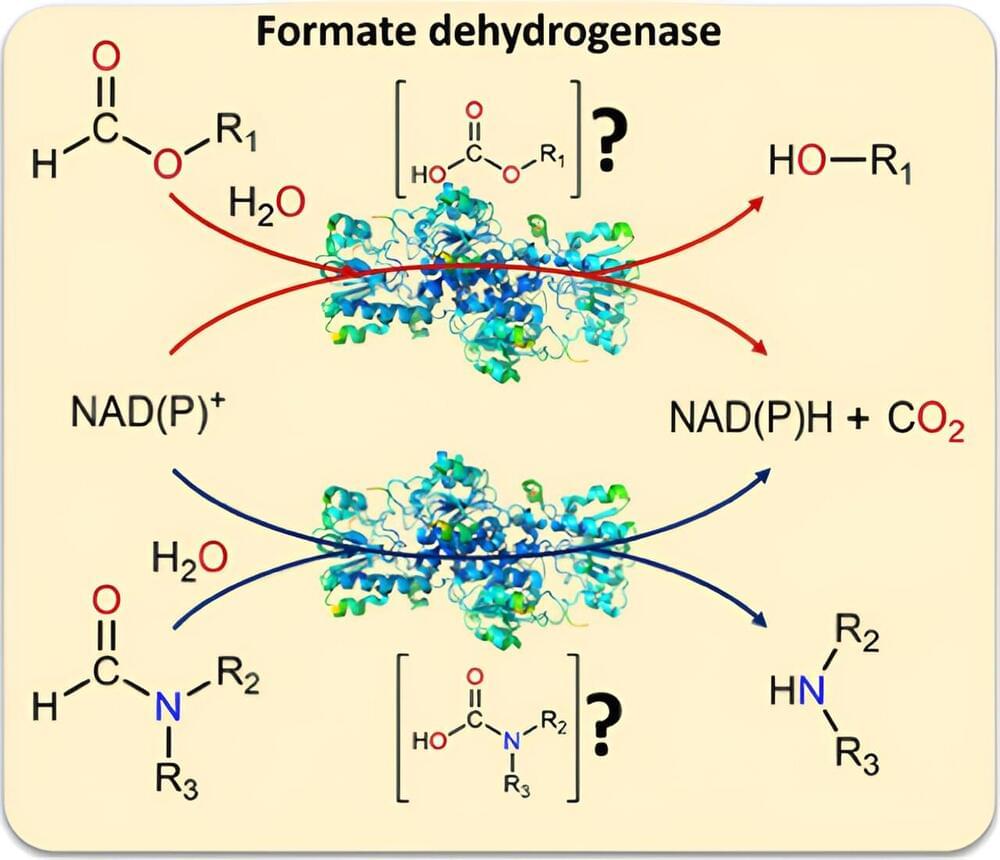

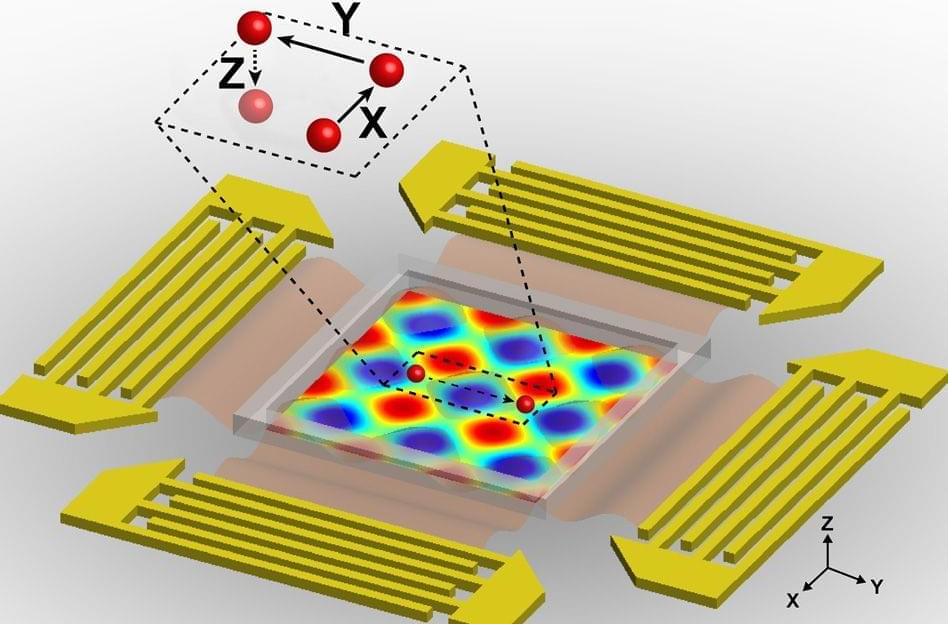

I believe that the nanotransfection using internal biocomputing will change psychiatric problems because it will physically repair problems with biocomputing rather chemical based computers. Also this could heal the software components aswell of the mind aswell.

Millions of Americans experience symptoms of a mental health condition each year, and the number of people seeking care is trending upward. While a mental health diagnosis may impact an individual’s daily life, it can also have a ripple effect across families, communities and even economies.

Here’s a closer look at the current state of mental health, including how many people experience mental health conditions and which populations are most at risk.