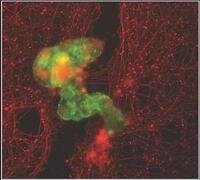

A new study by Dr Constantine Evans of Maynooth University and researchers at the University of Chicago and California Institute of Technology, published in Nature, shows how the molecules that build structures can do both the thinking and the doing.

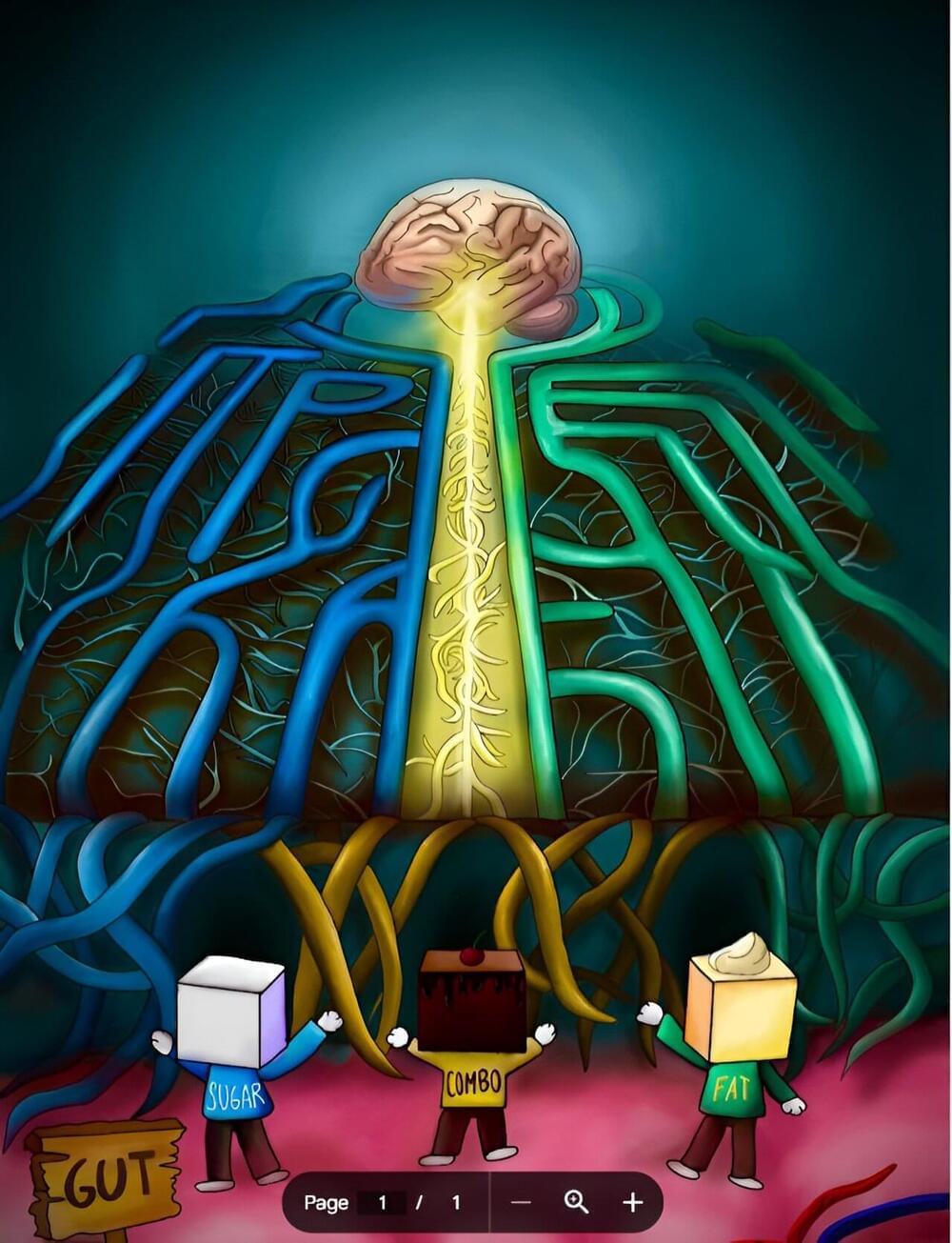

We tend to separate the brain and muscle – the brain does the thinking; the muscle does the doing. The brain takes in complex information about the world, makes decisions, while muscle merely executes.

This brain-muscle separation has also shaped how we think about the working within a single cell; some molecules within cells are seen as ‘thinkers’ that take in information about the chemical environment and decide what the cell needs to do for survival; separately, other molecules are seen as the ‘muscle’, building structures needed for survival.