Global optimization-based approaches such as basin hopping28,29,30,31, evolutionary algorithms32 and random structure search33 offer principled approaches to comprehensively navigating the ambiguity of active phase. However, these methods usually rely on skillful parameter adjustments and predefined conditions, and face challenges in exploring the entire configuration space and dealing with amorphous structures. The graph theory-based algorithms34,35,36,37, which can enumerate configurations for a specific adsorbate coverage on the surface with graph isomorphism algorithms, even on an asymmetric one. Nevertheless, these methods can only study the adsorbate coverage effect on the surface because the graph representation is insensitive to three-dimensional information, making it unable to consider subsurface and bulk structure sampling. Other geometric-based methods38,39 also have been developed for determining surface adsorption sites but still face difficulties when dealing with non-uniform materials or embedding sites in subsurface.

Topology, independent of metrics or coordinates, presents a novel approach that could potentially offer a comprehensive traversal of structural complexity. Persistent homology, an emerging technique in the field of topological data analysis, bridges the topology and real geometry by capturing geometric structures over various spatial scales through filtration and persistence40. Through embedding geometric information into topological invariants, which are the properties of topological spaces that remain unchanged under specific continuous deformations, it allows the monitoring of the “birth,” “death,” and “persistence” of isolated components, loops, and cavities across all geometric scales using topological measurements. Topological persistence is usually represented by persistent barcodes, where different horizontal line segments or bars denote homology generators41. Persistent homology has been successfully employed to the feature representation for machine learning42,43, molecular science44,45, materials science46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55, and computational biology56,57. The successful application motivates us to explore its potential as a sampling algorithm due to its capability of characterizing material structures multidimensionally.

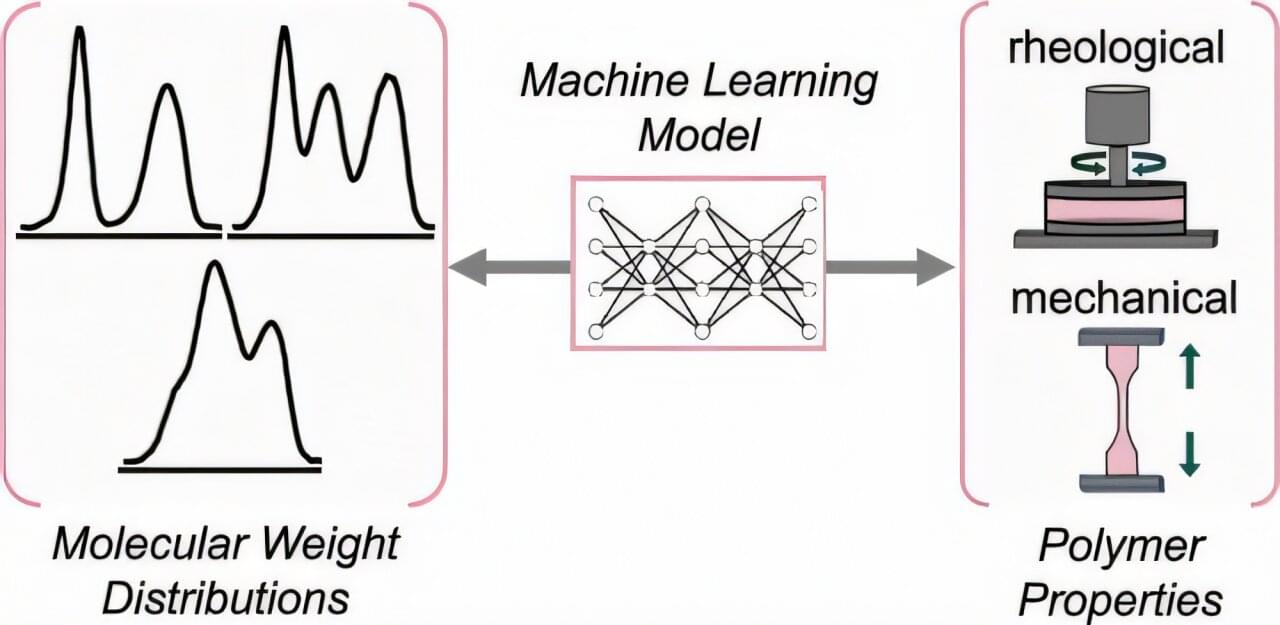

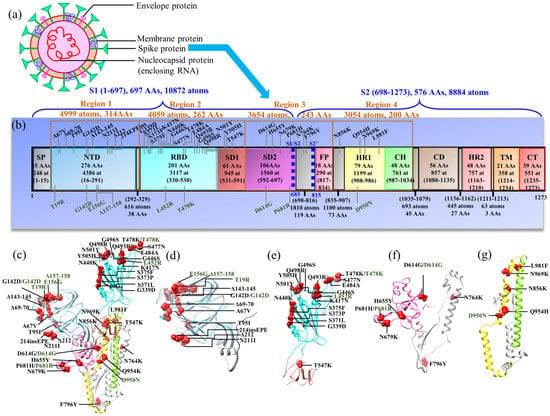

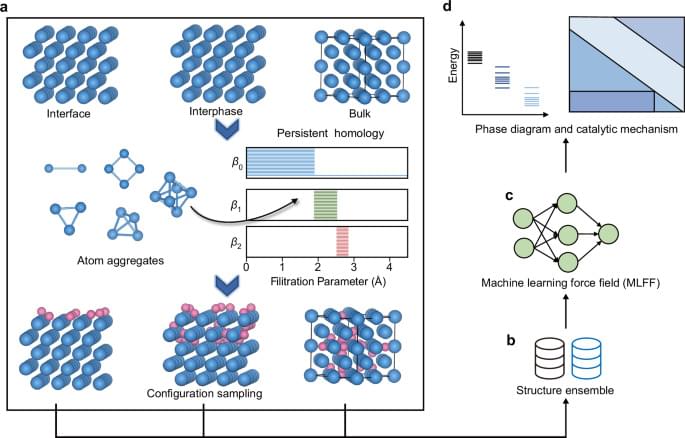

In this work, we introduce a topology-based automatic active phase exploration framework, enabling the thorough configuration sampling and efficient computation via MLFF. The core of this framework is a sampling algorithm (PH-SA) in which the persistent homology analysis is leveraged to detect the possible adsorption/embedding sites in space via a bottom-up approach. The PH-SA enables the exploration of interactions between surface, subsurface and even bulk phases with active species, without being limited by morphology and thus can be applied to periodical and amorphous structures. MLFF are then trained through transfer learning to enable rapid structural optimization of sampled configurations. Based on the energetic information, Pourbaix diagram is constructed to describe the response of active phase to external environmental conditions. We validated the effectiveness of the framework with two examples: the formation of Pd hydrides with slab models and the oxidation of Pt clusters in electrochemical conditions. The structure evolution process of these two systems was elucidated by screening 50,000 and 100,000 possible configurations, respectively. The predicted phase diagrams with varying external potentials and their intricate roles in shaping the mechanisms of CO2 electroreduction and oxygen reduction reaction were discussed, demonstrating close alignment with experimental observations. Our algorithm can be easily applied to other heterogeneous catalytic structures of interest and pave the way for the realization of automatic active phase analysis under realistic conditions.