Recent research in mice investigates a new, immunotherapy-based approach to treating Alzheimer’s disease aiming to clear toxic protein accumulations in the brain.

“It’s not much you can do about it. Other than fight it and if you fight and you quit, then you are not gonna make it,” he said.

The founders of this Malibu-based class say it challenges the mind and body to work together, getting stronger in the process.

John Wakefield, the creator and co-founder of drumboxing in California, told KCBS, “The connection with rhythm, tying it in with motor skills, really training the brain like you train the body putting it in a situation where it has to react.”

A medication used to treat diabetes appeared to halt the progression of Parkinson’s symptoms in a phase 2 trial of people in the early stages of the disease. While more research is needed to see how large the effect is and how long it might last, the news is encouraging in the hunt for new Parkinson’s treatments.

The challenge: More than 8.5 million people worldwide are living with Parkinson’s, a progressive neurodegenerative disease caused by the loss of brain cells that produce dopamine, which helps neurons communicate.

Common Parkinson’s symptoms include tremors, stiffness, and impaired cognition. Meds that replace dopamine can help alleviate those, but they don’t address the underlying cause — the loss of dopamine neurons — and so the disease progresses.

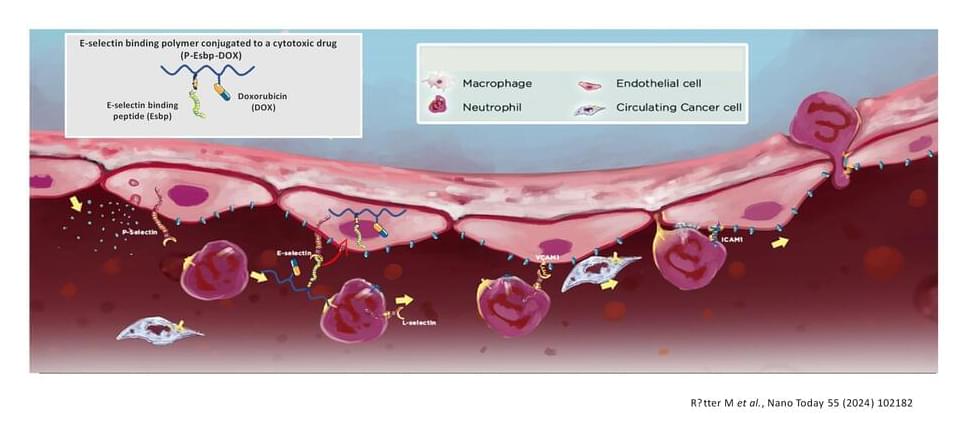

A nanosized polymer, developed by a research team from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, can selectively deliver chemotherapeutic drugs to blood vessels that feed tumors and metastases and has emerged as an effective treatment for advanced cancer. The polymer eliminates colorectal cancer liver metastases and prolongs mice survival after a single dose therapy.

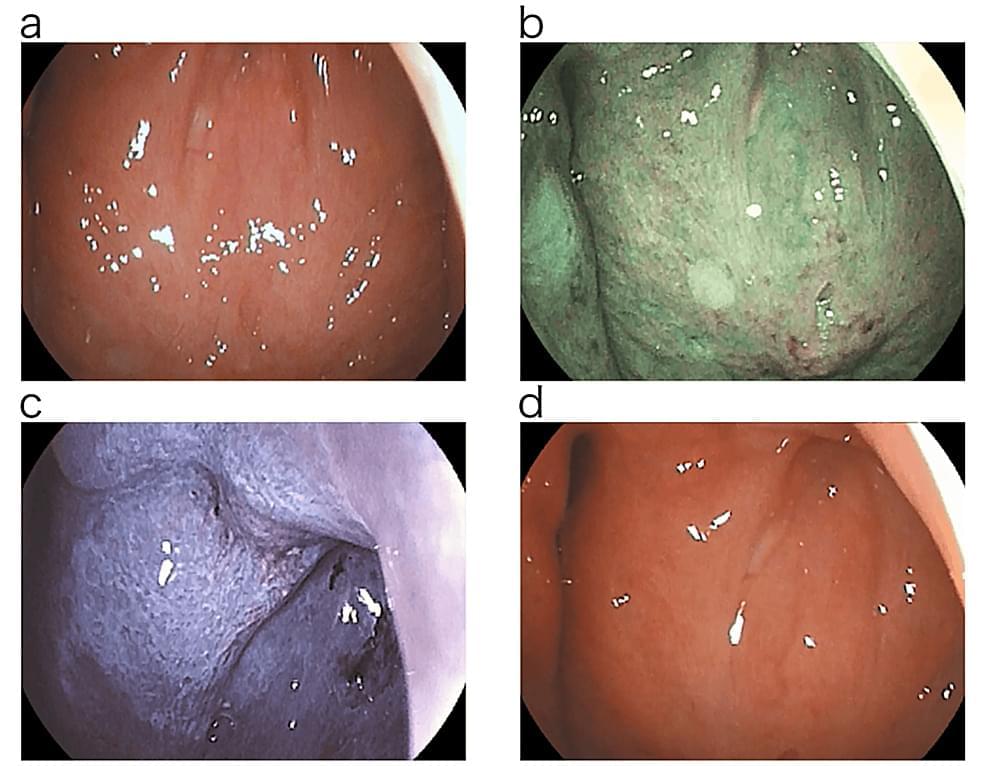

A case of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) with chronic epipharyngitis was treated with epipharyngeal abrasive therapy (EAT). The symptoms of ME/CFS improved along with the improvement of chronic epipharyngitis. The patient was followed up with endocrine and autonomic function tests. Endocrine function tests included salivary cortisol and salivary α-amylase activity. Salivary α-amylase activity was stimulated by EAT improved the diurnal variability of salivary cortisol secretion. Autonomic function tests included heart rate variability analysis by orthostatic stress test. EAT normalized parasympathetic and sympathetic reflexes over time and regulated autonomic balance. Based on the improvement of symptoms and test results, EAT was considered effective for ME/CFS. A literature review was conducted on the mechanism of the therapeutic effect of EAT on ME/CFS.

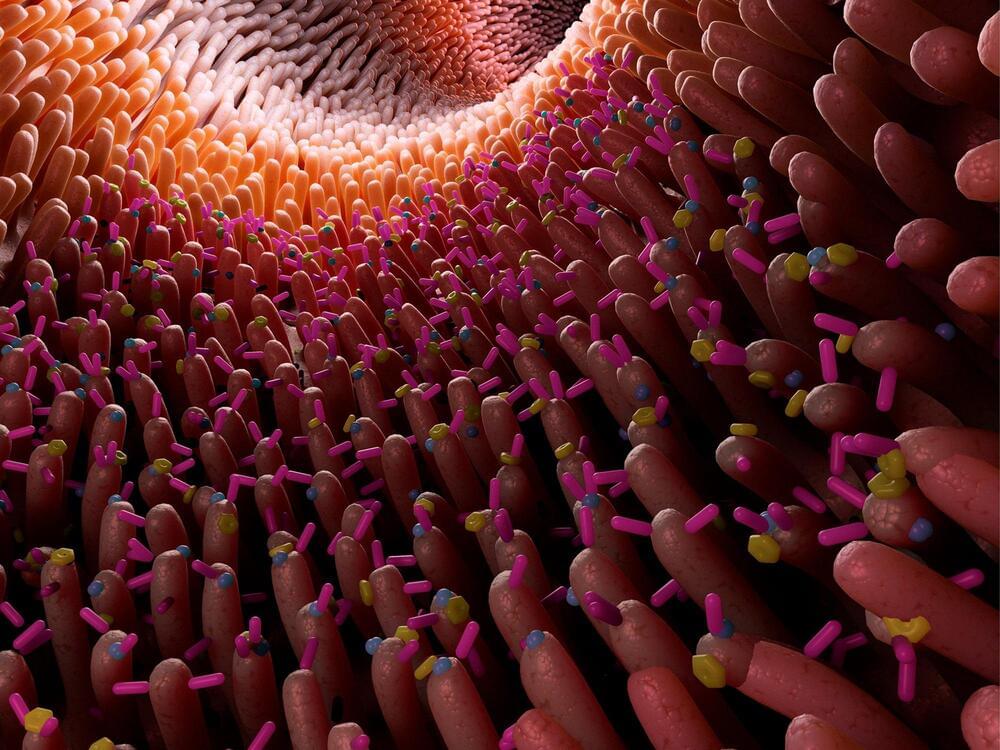

Alterations in the gut microbiome are associated with a range of diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, obesity, and inflammatory bowel disease.

Now, a team of researchers at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard along with Massachusetts General Hospital has found that microbes in the gut may affect cardiovascular disease as well. In a study published in Cell, the team has identified specific species of bacteria that consume cholesterol in the gut and may help lower cholesterol and heart disease risk in people.

Members of Ramnik Xavier’s lab, Broad’s Metabolomics Platform, and collaborators analyzed metabolites and microbial genomes from more than 1,400 participants in the Framingham Heart Study, a decades-long project focused on risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

An international team including researchers from the University of Würzburg has succeeded in creating a special state of superconductivity. This discovery could advance the development of quantum computers.

Superconductors are materials that can conduct electricity without electrical resistance – making them the ideal base material for electronic components in MRI machines, magnetic levitation trains, and even particle accelerators. However, conventional superconductors are easily disturbed by magnetism. An international group of researchers has now succeeded in building a hybrid device consisting of a stable proximitized-superconductor enhanced by magnetism and whose function can be specifically controlled.

They combined the superconductor with a special semiconductor material known as a topological insulator. “Topological insulators are materials that conduct electricity on their surface but not inside. This is due to their unique topological structure, i.e. the special arrangement of the electrons,” explains Professor Charles Gould, a physicist at the Institute for Topological Insulators at the University of Würzburg (JMU). “The exciting thing is that we can equip topological insulators with magnetic atoms so that they can be controlled by a magnet.”

Australian researchers have discovered a previously unknown rogue immune cell that can cause poor antibody responses in chronic viral infections. The finding, published in the journal, Immunity, may lead to earlier intervention and possibly prevention of some types of viral infections such as HIV or hepatitis.

While an estimated 5 million Americans live with a disability that is related to traumatic brain injury (TBI), there are few treatment options for TBIs, which can affect people in a number of occupations like professional sports or some military positions, as well as anyone who suffers head trauma. But scientists have now found that a protein called TDP-43 may promote nerve damage immediately following an injury. When another protein was blocked in a mouse model and in human cell lines, this TDP-43-mediated damaged was prevented and some cell death was halted. These findings, which were reported in Cell Stem Cell, could help scientists develop treatment options for TBIs.

“There’s really nothing out there that can prevent the injury or trauma to the brain that cause nerve cell damage,” said corresponding study author Justin Ichida of the University of Southern California. “In more acute stages, patients can have difficulty concentrating and have extreme sensitivity to light and noise. Long term, there is a strong correlation between traumatic brain injury and neurodegenerative diseases, which can ultimately be fatal.”