New research identifies some of the genes that could help to explain why lung cancer incidence rises with age but declines after the age of 75.

A new microscopy method has allowed researchers to detect tiny changes in the atomic-level architecture of crystalline materials like advanced steels for ship hulls and custom silicon for electronics. It could advance our ability to understand the fundamental origins of materials properties and behaviour.

In a paper published today in Nature Materials, researchers from the University of Sydney’s School of Aerospace, Mechanical and Mechatronic Engineering introduced a new way to decode the atomic relationships within materials.

The breakthrough could assist in the development of stronger and lighter alloys for the aerospace industry, new generation semiconductors for electronics, and improved magnets for electric motors. It could also enable the creation of sustainable, efficient and cost-effective products.

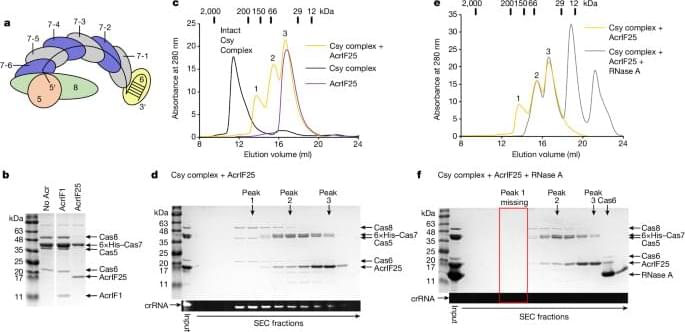

Researchers at Rice University are making strides in understanding how chromosome structures change throughout the cell’s life cycle. Their study on motorized processes that actively influence the organization of chromosomes appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

“This research provides a deeper understanding of how motorized processes shape chromosome structures and influence cellular functions,” said Peter Wolynes, study co-author and the D.R. Bullard-Welch Foundation Professor of Science. Wolynes is also a professor of chemistry, biosciences, physics and astronomy and the co-director of the Center for Theoretical Biological Physics (CTBP).

The research introduces two types of motorized chain models: swimming motors and grappling motors. These motors play distinct roles in manipulating chromosome structure.

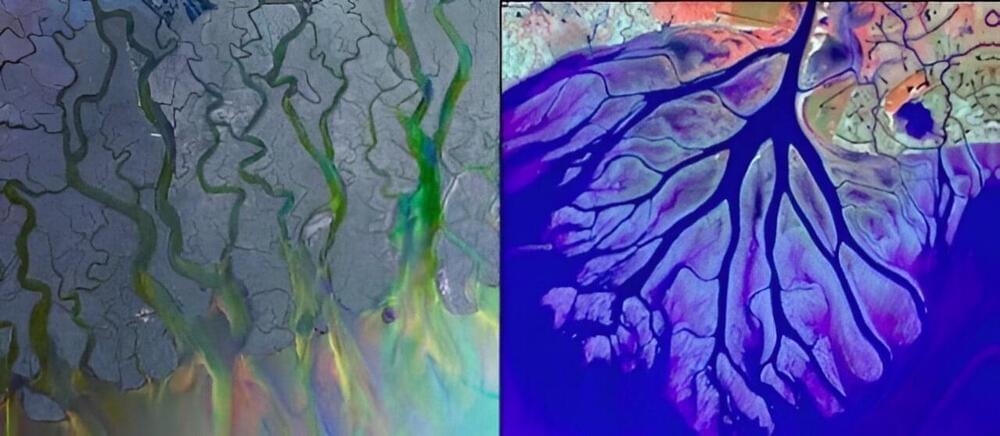

Understanding how transport networks, such as river systems, form and evolve is crucial to optimizing their stability and resilience. It turns out that networks are not all alike. Tree-like structures are adequate for transport, while networks containing loops are more damage-resistant. What conditions favor the formation of loops?

Researchers from the Faculty of Physics at the University of Warsaw and the University of Arkansas sought to answer this question. The findings, published in Physical Review Letters, show that networks tend to form stable loop structures when flow fluctuations are appropriately tuned. This finding will allow us to understand the structure of dynamic transport networks better.

Transport networks, like blood vessels or river systems, are essential for many natural and human-made systems. Understanding how these networks form and grow is crucial for optimizing their stability and resilience.

New findings reveal that individuals with an average sense of smell may unknowingly be living with natural gas leaks. According to a peer-reviewed study in the scientific journal Environmental Research Letters, minor leaks can deteriorate indoor air quality by emitting various hazardous pollutants, such as benzene—a carcinogen detected in 97% of natural gas samples throughout North America.

“While these smaller leaks are not large enough to cause gas explosions, hard-to-smell leaks are common,” said lead author and PSE Healthy Energy Scientist Sebastian Rowland. “The fact that they are so small makes them hard to identify and fix, which can lead to a persistent indoor source of benzene and methane.”

Researchers found that inhibiting the degradation of vitamin B6 in cells using 7,8-Dihydroxyflavone enhances brain functions and could offer a new treatment method for mental and neurodegenerative disorders.

Vitamin B6 plays a crucial role in brain metabolism. Consequently, low levels of vitamin B6 are linked to memory and learning impairments, depressive moods, and clinical depression in various mental disorders. In the elderly, insufficient vitamin B6 is associated with memory decline and dementia.

Although some of these observations were made decades ago, the exact role of vitamin B6 in mental illness is still largely unclear. What is clear, however, is that an increased intake of vitamin B6 alone, for example in the form of dietary supplements, is insufficient to prevent or treat disorders of brain function.

Researchers have advanced their understanding of how drugs interact with connexin molecules. Connexins create channels that enable direct communication between adjacent cells. Dysfunctions in these channels play a role in neurological and cardiac disorders. This enhanced knowledge of drug binding and action on connexins could aid in developing treatments for these diseases.

Today we use many electronic means to communicate, but sometimes dropping a note in a neighbor’s letter box or leaving a cake on a doorstep is most effective. Cells too have ways to send direct messages to their neighbors.

Adjacent cells can communicate directly through relatively large channels called gap junctions, which allow cells to freely exchange small molecules and ions with each other or with the outside environment. In this way, they can coordinate activities in the tissues or organs that they compose and maintain homeostasis.

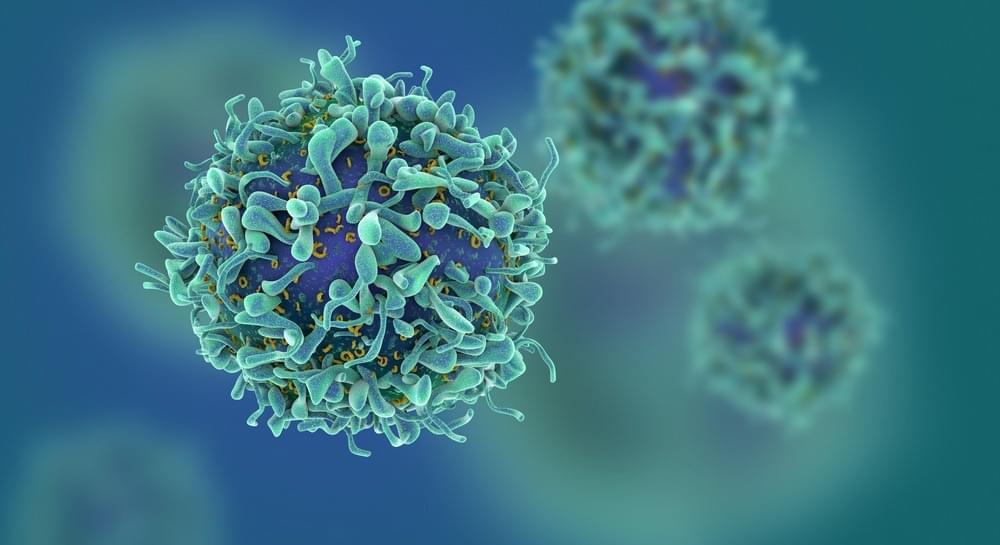

In a recent study published in Immunology, researchers investigated populations of regulatory T cells (Treg), a type of white blood cell, in various tissues.

Researchers at the University of Cambridge have identified that regulatory T cells exist as a large, mobile population that continuously travels through the body to locate and repair damaged tissue.