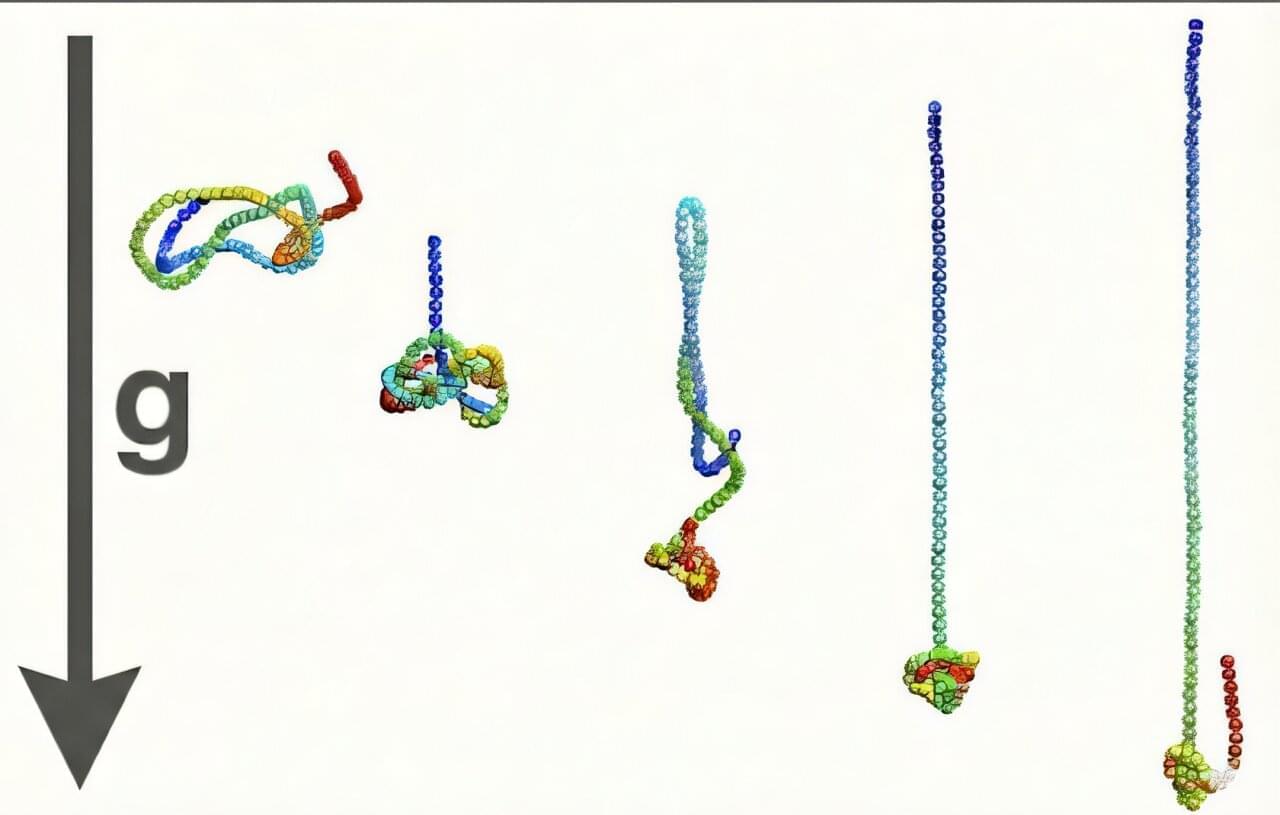

Knots are everywhere—from tangled headphones to DNA strands packed inside viruses—but how an isolated filament can knot itself without collisions or external agitation has remained a longstanding puzzle in soft-matter physics.

Now, a team of researchers at Rice University, Georgetown University and the University of Trento in Italy has uncovered a surprising physical mechanism that explains how a single filament, even one too short or too stiff to easily wrap around itself, can form a knot while sinking through a fluid under strong gravitational forces.

The discovery, published in Physical Review Letters, provides new insight into the physics of polymer dynamics, with implications ranging from understanding how DNA behaves under confinement to designing next-generation soft materials and nanostructures.