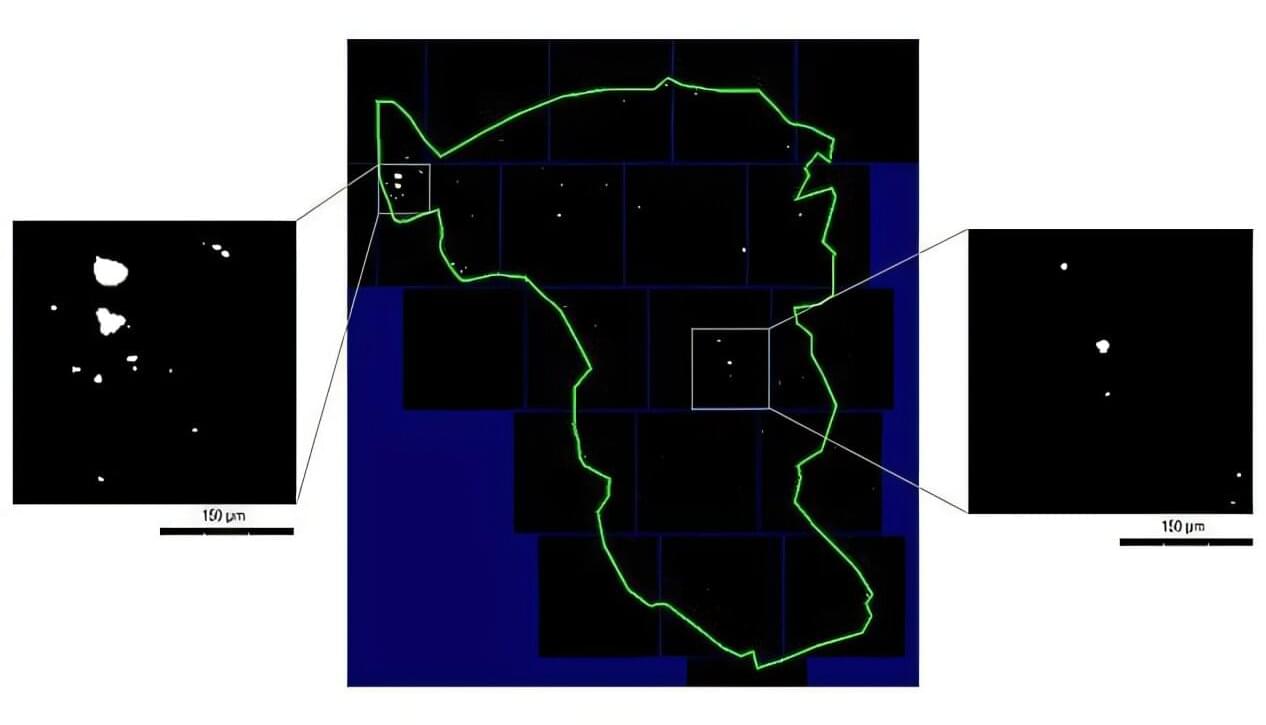

Titanium micro-particles in the oral mucosa around dental implants are common. This is shown in a new study from the University of Gothenburg and Uppsala University, which also identified 14 genes that may be affected by these particles.

Registry data indicate that about 5% of all adults in Sweden have dental implants —and potentially also titanium particles in the tissue surrounding the implants. According to the researchers, there is no reason for concern, but more knowledge is needed.

“Titanium is a well-studied material that has been used for decades. It is biocompatible and safe, but our findings show that we need to better understand what happens to the micro-particles over time. Do they remain in the tissue or spread elsewhere in the body?” says Tord Berglundh, senior professor of periodontology at Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg.