Our brains have a remarkable knack for picking out individual voices in a noisy environment, like a crowded coffee shop or a busy city street. This is something that even the most advanced hearing aids struggle to do. But now Columbia engineers are announcing an experimental technology that mimics the brain’s natural aptitude for detecting and amplifying any one voice from many. Powered by artificial intelligence, this brain-controlled hearing aid acts as an automatic filter, monitoring wearers’ brain waves and boosting the voice they want to focus on.

Though still in early stages of development, the technology is a significant step toward better hearing aids that would enable wearers to converse with the people around them seamlessly and efficiently. This achievement is described today in Science Advances.

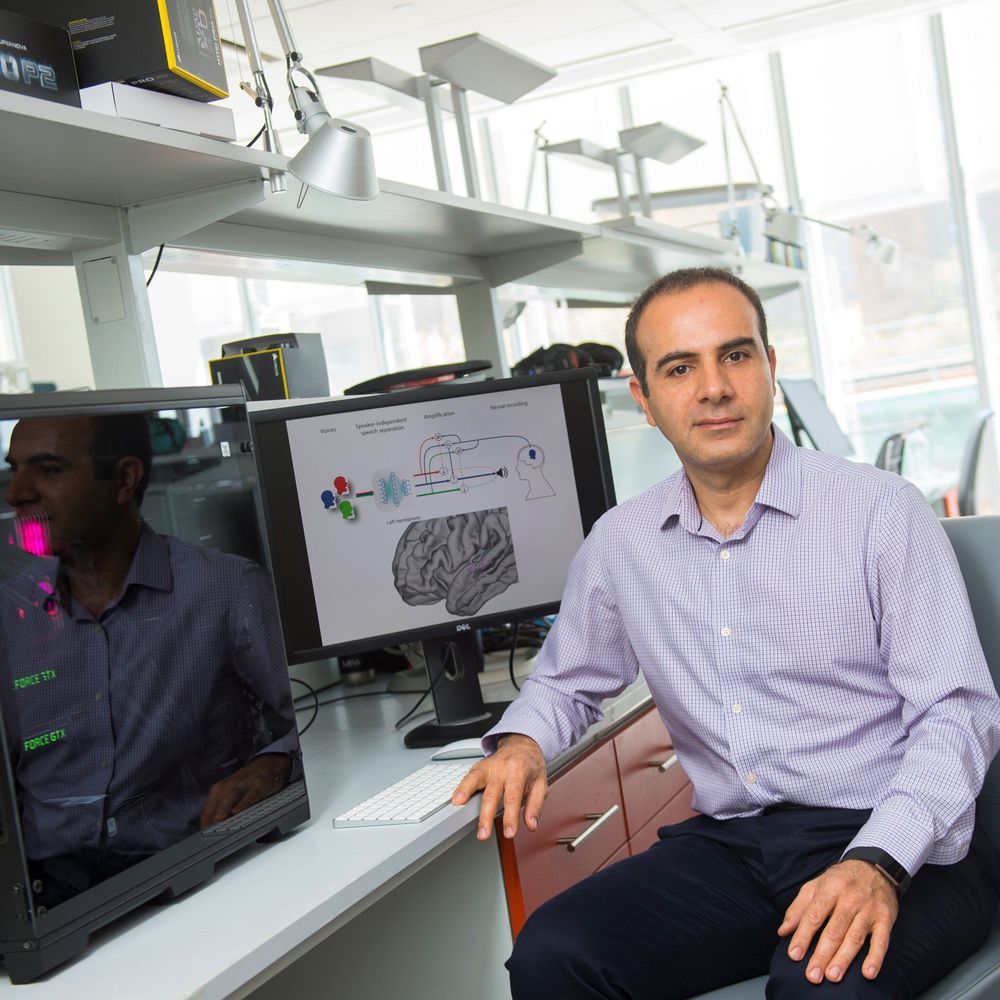

“The brain area that processes sound is extraordinarily sensitive and powerful; it can amplify one voice over others, seemingly effortlessly, while today’s hearings aids still pale in comparison,” said Nima Mesgarani, Ph.D., a principal investigator at Columbia’s Mortimer B. Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute and the paper’s senior author. “By creating a device that harnesses the power of the brain itself, we hope our work will lead to technological improvements that enable the hundreds of millions of hearing-impaired people worldwide to communicate just as easily as their friends and family do.”