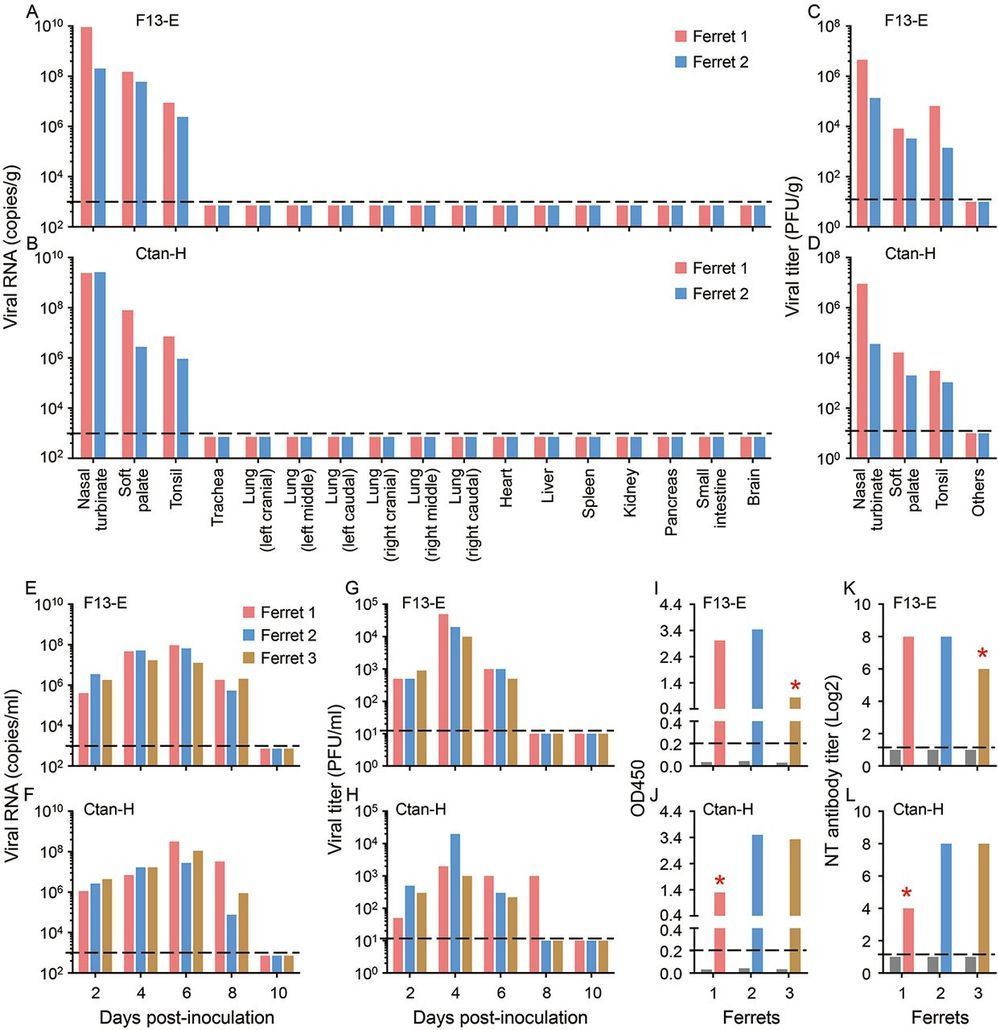

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causes the infectious disease COVID-19, which was first reported in Wuhan, China in December, 2019. Despite the tremendous efforts to control the disease, COVID-19 has now spread to over 100 countries and caused a global pandemic. SARS-CoV-2 is thought to have originated in bats; however, the intermediate animal sources of the virus are completely unknown. Here, we investigated the susceptibility of ferrets and animals in close contact with humans to SARS-CoV-2. We found that SARS-CoV-2 replicates poorly in dogs, pigs, chickens, and ducks, but ferrets and cats are permissive to infection. We found experimentally that cats are susceptible to airborne infection. Our study provides important insights into the animal models for SARS-CoV-2 and animal management for COVID-19 control.

In late December 2019, an unusual pneumonia emerged in humans in Wuhan, China, and rapidly spread internationally, raising global public health concerns. The causative pathogen was identified as a novel coronavirus (1–16) that was named Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) on the basis of a phylogenetic analysis of related coronaviruses by the Coronavirus Study Group of the International Committee on Virus Taxonomy (17); the disease it causes was subsequently designated COVID-19 by the World Health Organization (WHO). Despite tremendous efforts to control the COVID-19 outbreak, the disease is still spreading. As of March 11, 2020, SARS-CoV-2 infections have been reported in more than 100 countries, and 118,326 human cases have been confirmed, with 4,292 fatalities (18). COVID-19 has now been announced as a pandemic by WHO.

Although SARS-CoV-96.2% identity at the nucleotide level with the coronavirus RaTG13, which was detected in horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus spp) in Yunnan province in 2013 (3), it has not previously been detected in humans or other animals. The emerging situation raises many urgent questions. Could the widely disseminated viruses transmit to other animal species, which then become reservoirs of infection? The SARS-CoV-2 infection has a wide clinical spectrum in humans, from mild infection to death, but how does the virus behave in other animals? As efforts are made for vaccine and antiviral drug development, which animal(s) can be used most precisely to model the efficacy of such control measures in humans? To address these questions, we evaluated the susceptibility of different model laboratory animals, as well as companion and domestic animals to SARS-CoV-2.