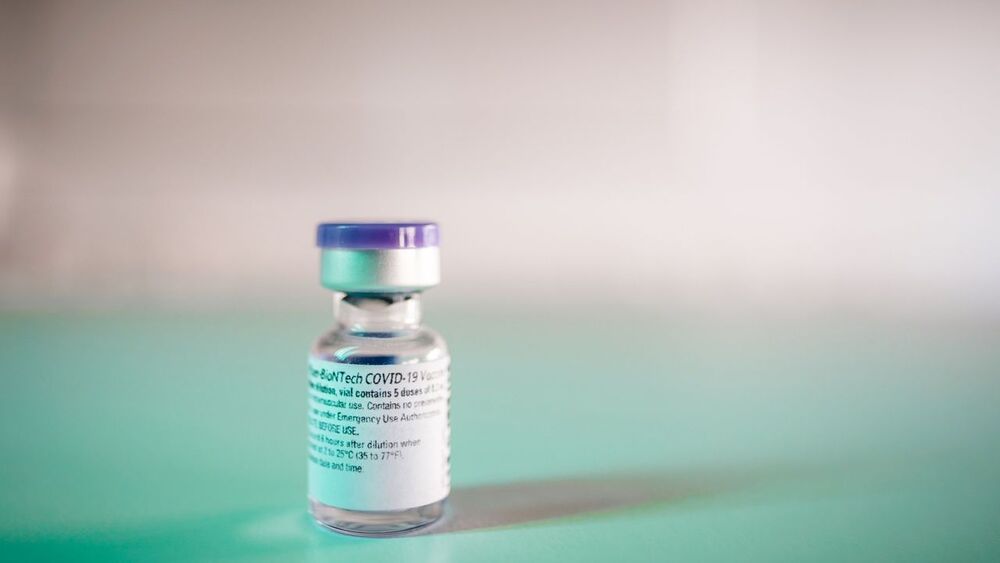

MHRA will only become fully independent on 1 January 2021, following Brexit, but U.K. regulations allow it to grant authorizations on an emergency basis. The United Kingdom has bought 40 million doses of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine—enough for 20 million people—and health secretary Matt Hancock today announced the first 800,000 doses will be available next week. The rollout will prioritize health workers as well as the elderly and other vulnerable populations, but the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation has yet to offer its final guidance on the exact priorities.

Russia on 11 August allowed its COVID-19 vaccine, developed by the Gamaleya Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology, to be used on certain groups of people, and China has granted emergency use authorizations (EUAs) for several vaccines and has already vaccinated hundreds of thousands of people with them. A few other countries, including the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, have issued an EUA for one of the Chinese vaccines, produced by Sinopharm.

The Pfizer vaccine, whose key ingredient is messenger RNA that encodes the spike protein of the pandemic coronavirus, was found to have 95% efficacy, a clinical trial measurement of effectiveness, in a phase III trial in 43,000 people. But it presents logistical challenges for a widescale and rapid rollout, as it requires storage at −70°C. The lesser demands of other vaccines—including a candidate developed by the University of Oxford and AstraZeneca—mean they will likely still play an important role in providing vaccinations for the whole U.K. population—and for global coverage, according to Michael Head, a global health researcher at the University of Southampton, “but, for now, this is wonderful news to wake up to.”