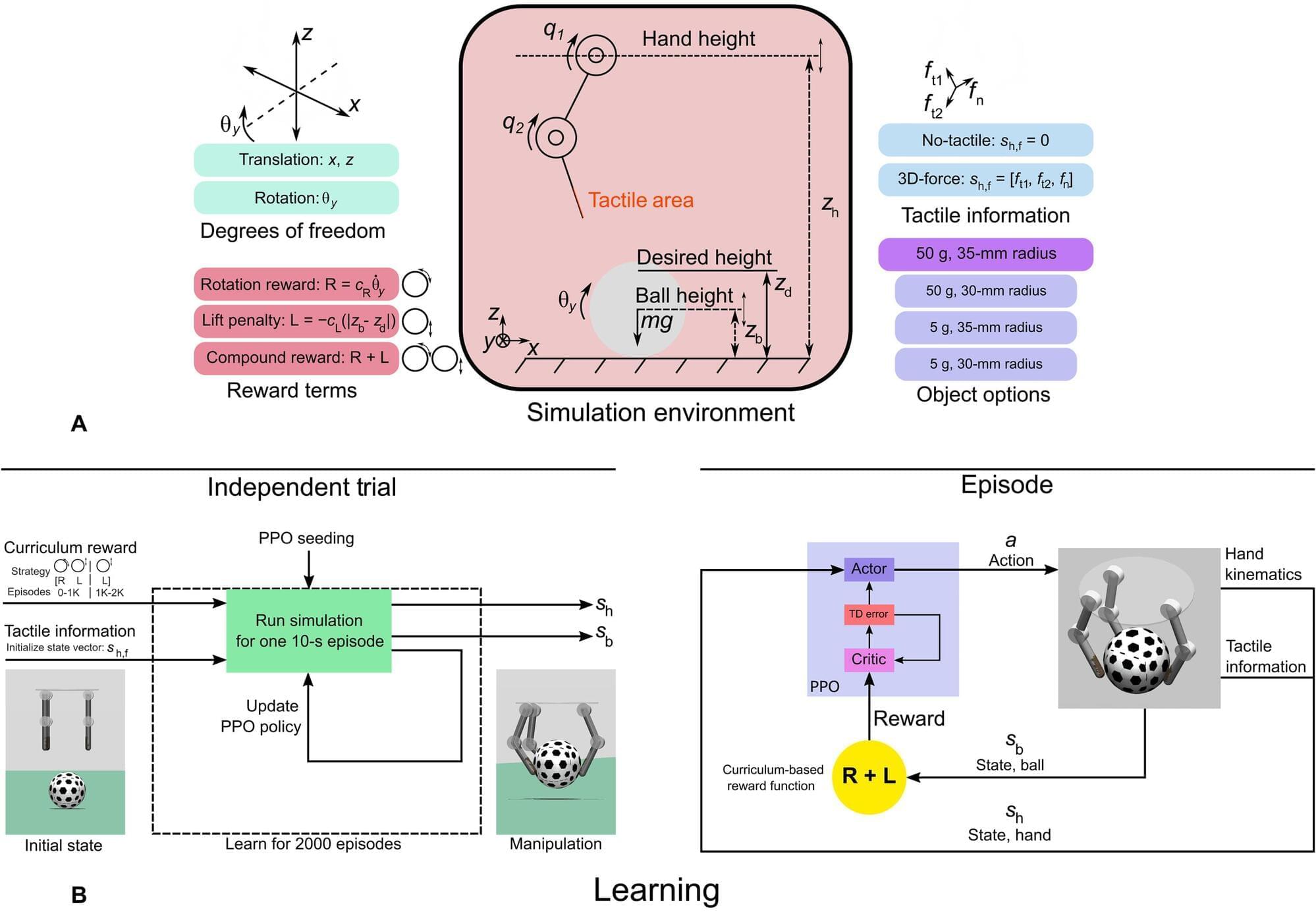

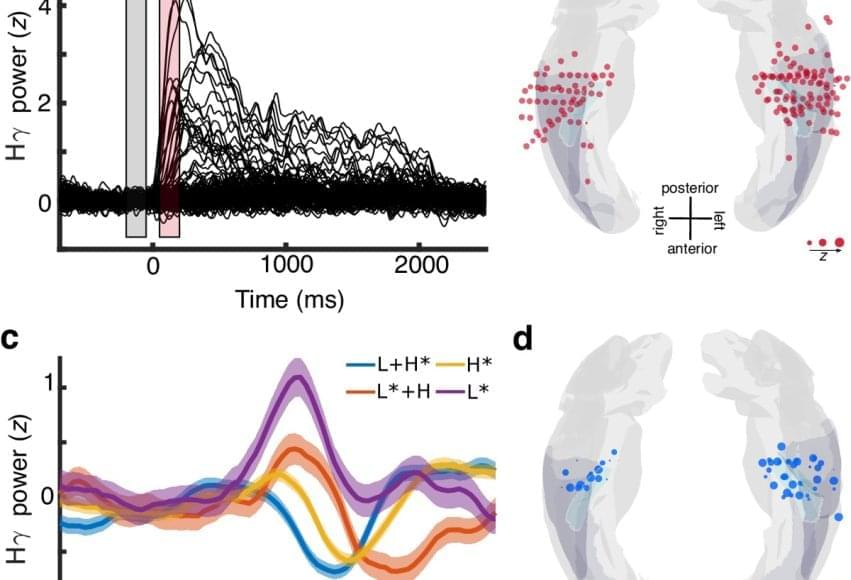

How does a robotic arm or a prosthetic hand learn a complex task like grasping and rotating a ball? The challenge for the human, prosthetic or robotic hand has always been to correctly learn to control the fingers to exert forces on an object.

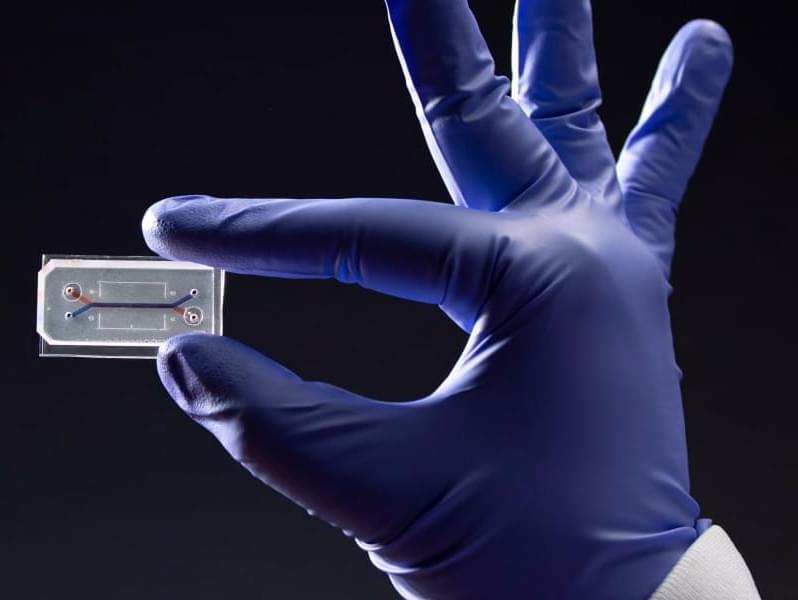

The sensitive skin and nerve endings that cover our hands have been attributed with helping us learn and adapt to our manipulation, so roboticists have insisted on incorporating sensors into robotic hands. But–given that you can still learn to handle objects with gloves on– there must be something else at play.

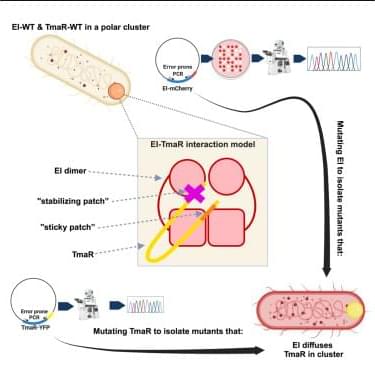

This mystery is what inspired researchers in the ValeroLab in the Viterbi School of Engineering to explore if tactile sensation is really always necessary for learning to control the fingers.