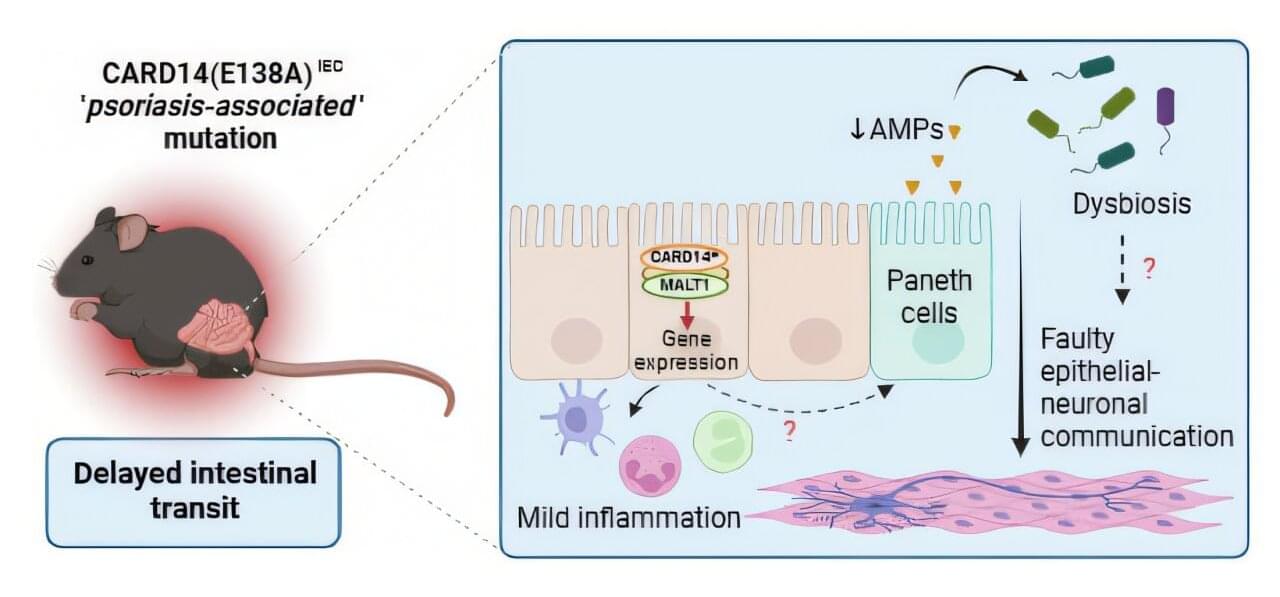

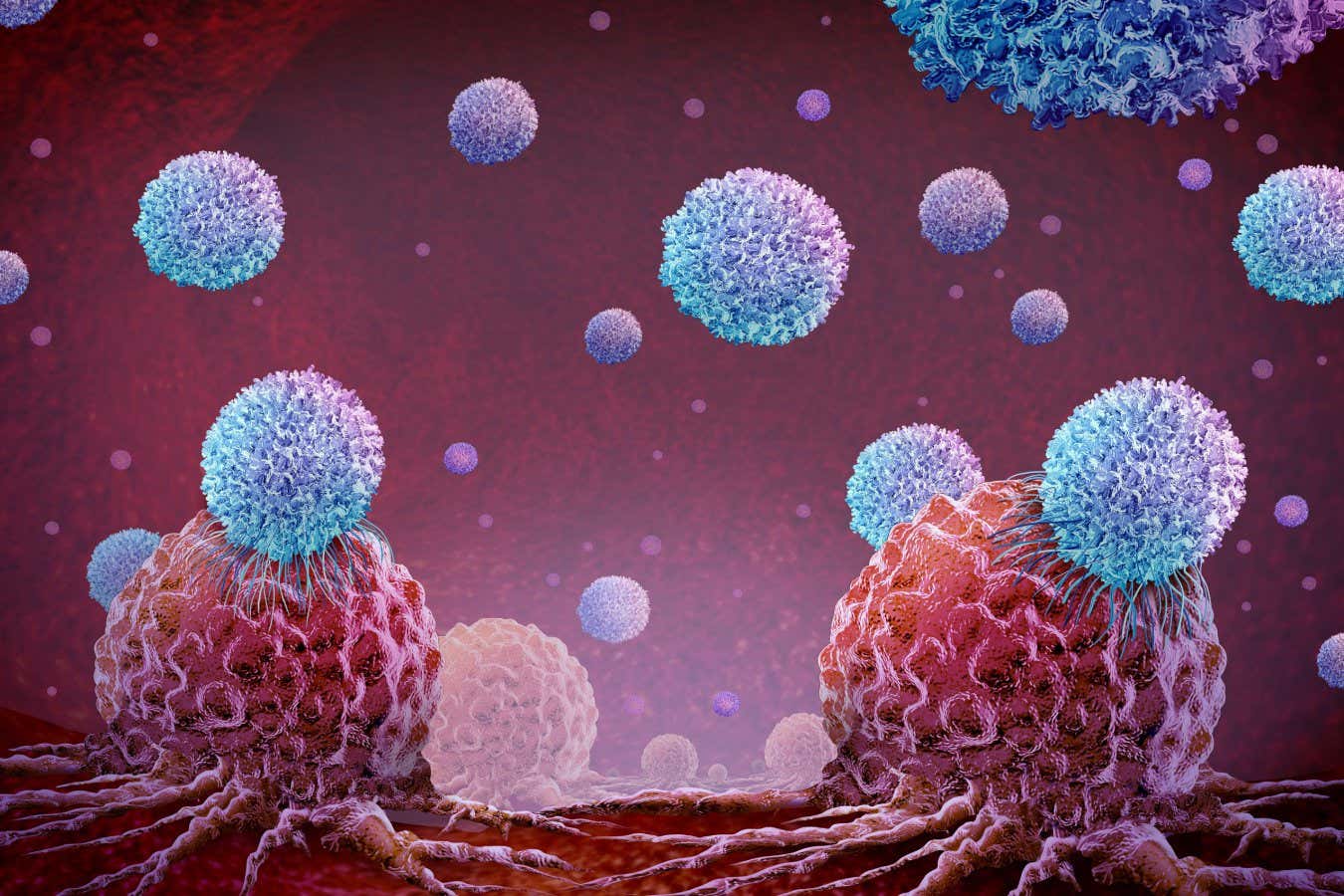

The immune system works to identify and target invading pathogens. Specifically, our bodies work to get rid of any harmful infections by employing a two-part immune response. The first wave of immunity is the innate immune system. This initial reaction is broad and non-specific with innate cells circulating throughout the body to detect foreign pathogens. These cells that are involved include neutrophils, macrophages, eosinophils, basophils, and dendritic cells. Once cells detect an issue, they alert the rest of the body to completely filter out the infection. Importantly, the second wave of immunity, or the adaptive immune system, elicits a strong, specific response that target pathogens the innate immune system cannot neutralize.

Adaptive immunity builds to generate robust protection against aggressive diseases. The cells that make up this response include B and T cells. B cells are mainly responsible for generating antibodies to neutralize and signal infections throughout the body. T cells are the drivers that get rid of disease. T cell activity destroys infected cells and other pathogens lingering throughout the body or site of infection. The adaptive immune response is also critical for immune memory. Once someone experiences a disease and recovers, adaptive immune cells will remember that pathogen next time it enters the body — this is how vaccines work. A patient is injected with a non-harmful virus to expose the immune system. Immediately, the body will respond and destroy the virus. However, a few T cells will also be generated to targeted similar viruses in the future. As a result, when a patient is exposed to the infection again, they will be protected and not experience symptoms.

T cells are critical for any disease or infection, including cancer. Many immunotherapies currently being develop involve activating and directing T cells to the site of the tumor. However, immunotherapies have limited efficacy due to various mechanisms around the tumor that suppress immunity. Scientists are working to understand T cell biology to develop better immunotherapies and more accurately predict treatment outcomes in patients.