😗

Martian soil is generally poor for growing plants, but researchers have used CRISPR to create gene-edited rice that might be able to germinate and grow despite the hostile habitat.

By Leah Crane

😗

Martian soil is generally poor for growing plants, but researchers have used CRISPR to create gene-edited rice that might be able to germinate and grow despite the hostile habitat.

By Leah Crane

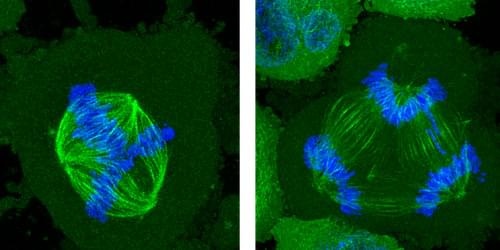

Segregation of chromosomes in dividing cells can be disrupted if the cells are constrained by their surroundings.

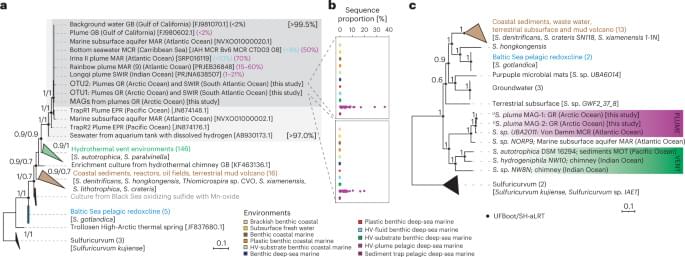

One of the aberrant features of cancer cells is a failure to distribute chromosomes properly when the cells divide. Researchers have now found that a specific problem with the chromosome-distribution machinery can become more common in cancer cells confined within shallow microscopic channels—but also that, surprisingly, increasing the physical constraints can suppress these errors [1]. Such confinement mimics the effects of crowding by surrounding cells in a tumor, and the researchers believe the results might help to explain what goes awry in cancers and perhaps offer clues to how it might be put right.

In a healthy, dividing cell, after the genome is replicated, the chromosomes are segregated into two groups. Both groups are bound to the mitotic spindle, a bundle of aligned filaments (called microtubules) that are pinched together at the ends into structures called poles. The chromosomes are then drawn along the microtubules toward the poles. A key cause of improper chromosome segregation in cancer cells is the formation of spindles with more than two poles. Multipolar spindle formation inside living organisms may differ from the phenomenon when observed in cells grown in a dish [2], so it is possible that the confining effect of the surrounding cells in a tissue has some influence on this process.

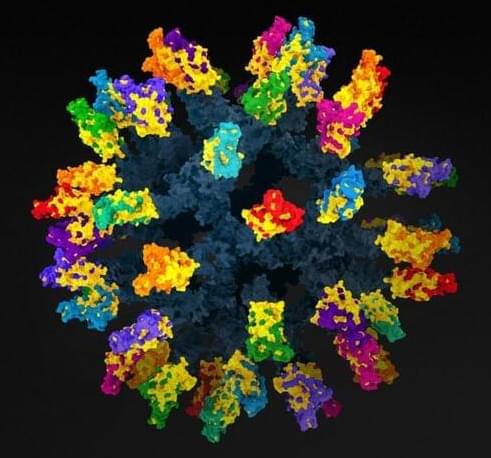

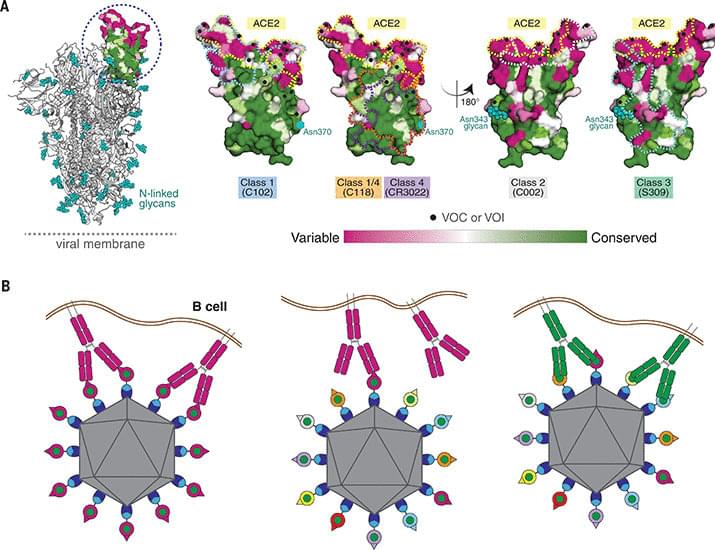

Year 2022 😗😁 Basically more thought on this virus seems more like a foglet biotechnology so it would stand to reason that a nanotechnology with biotechnology could solve the universal vaccine.

Ending the covid pandemic might well require a vaccine that protects against any new strains. Researchers may have found a strategy that will work.

(NewsNation) — Studies have shown that Alzheimer’s may become the defining disease of the baby boomer generation.

According to The Alzheimer’s Association, the number of people age 65 and over living with Alzheimer’s now is nearly 7 million. That number is expected to rise to over 13 million by 2050.

Physician and best-selling author Dr. Ian Smith says it’s not known exactly what causes Alzheimer’s.

What if death was not the end? What if, instead of saying our final goodbyes to loved ones, we could freeze their bodies and bring them back to life once medical technology has advanced enough to cure their fatal illnesses? This is the mission of Tomorrow Biostasis, a Berlin-based startup that specializes in cryopreservation.

Cryopreservation, also known as biostasis or cryonics, is the process of preserving a human body (or brain) in a state of suspended animation, with the hope that it can be revived in the future when medical technology has advanced enough to treat the original cause of death. This may seem like science fiction, but it is a legitimate scientific procedure, and Tomorrow Biostasis is one of the few companies in the world that offers this service.

Dr Emil Kendziorra, co-founder and CEO of Tomorrow Biostasis explained that the goal of cryopreservation is to extend life by preserving the body until a cure can be found for the original illness. He emphasized that cryopreservation is not a form of immortality, but rather a way to give people a second chance at life.

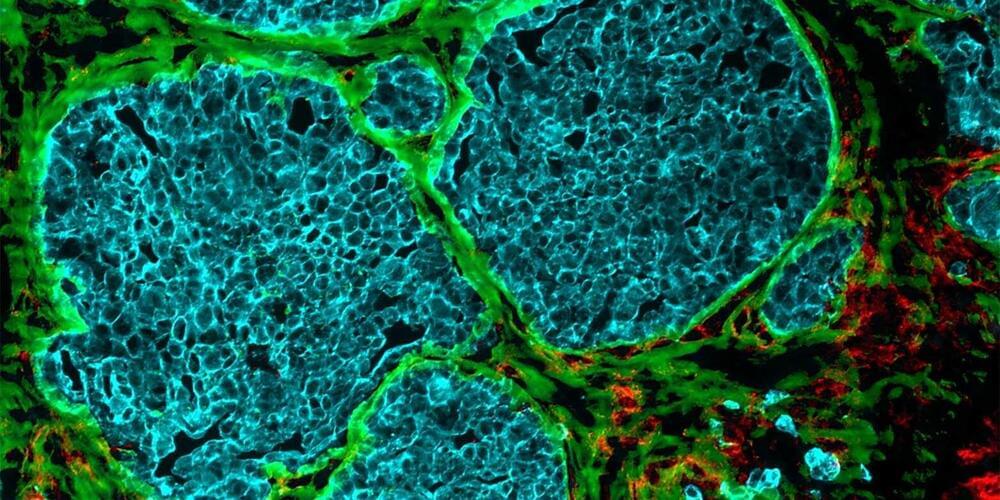

Increasingly dense cell clusters in growing tumors convert blood vessels into fiber-filled channels. This makes immune cells less effective, as findings by researchers from ETH Zurich and the University of Strasbourg suggest. Their research is published in Matrix Biology.

It was almost ten years ago that researchers first observed that tumors occurring in different cancers—including colorectal cancer, breast cancer and melanoma—exhibit channels leading from the surface to the inside of the cell cluster. But how these channels form, and what functions they perform, long remained a mystery.

Through a series of elaborate and detailed experiments, the research groups led by Viola Vogel, Professor of Applied Mechanobiology at ETH Zurich, and Gertraud Orend from the University of Strasbourg have found possible answers to these questions. There is a great deal of evidence to suggest that these channels, which the researchers have dubbed tumor tracks, were once blood vessels.

Brainoids — tiny clumps of human brain cells — are being turned into living artificial intelligence machines, capable of carrying out tasks like solving complex equations. The team finds out how these brain organoids compare to normal computer-based AIs, and they explore the ethics of it all.

Sickle cell disease is now curable, thanks to a pioneering trial with CRISPR gene editing. The team shares the story of a woman whose life has been transformed by the treatment.

We can now hear the sound of the afterglow of the big bang, the radiation in the universe known as the cosmic microwave background. The team shares the eerie piece that has been transposed for human ears, named by researchers The Echo of Eternity.