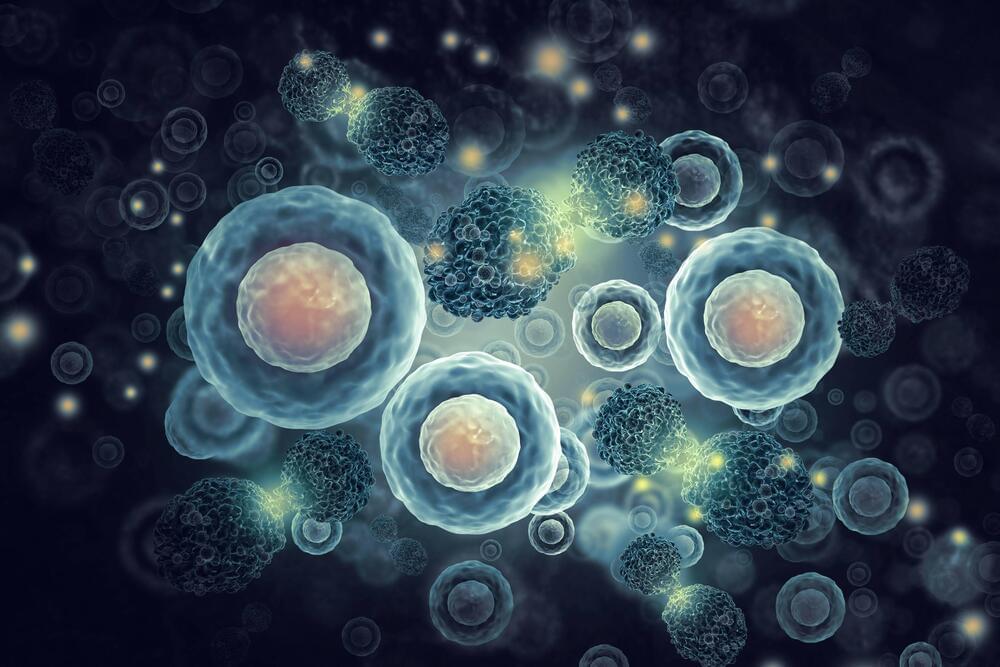

Researchers have discovered that senescent pigment cells in skin moles can stimulate robust hair growth, challenging the belief that these cells impede regeneration. The study showed that molecules osteopontin and CD44 play a key role in this process, potentially opening new avenues for therapies for common hair loss conditions.

The process by which aged, or senescent, pigment-making cells in the skin cause significant growth of hair inside skin moles, called nevi, has been identified by a research team led by the University of California, Irvine. The discovery may offer a road map for an entirely new generation of molecular therapies for androgenetic alopecia, a common form of hair loss in both women and men.

The study, published on June 21 in the journal Nature, describes the essential role that the osteopontin and CD44 molecules play in activating hair growth inside hairy skin nevi. These skin nevi accumulate particularly large numbers of senescent pigment cells and yet display very robust hair growth.