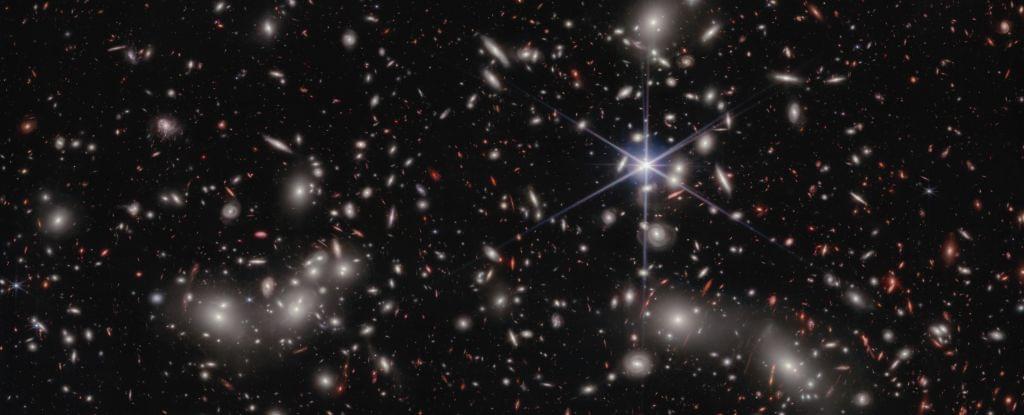

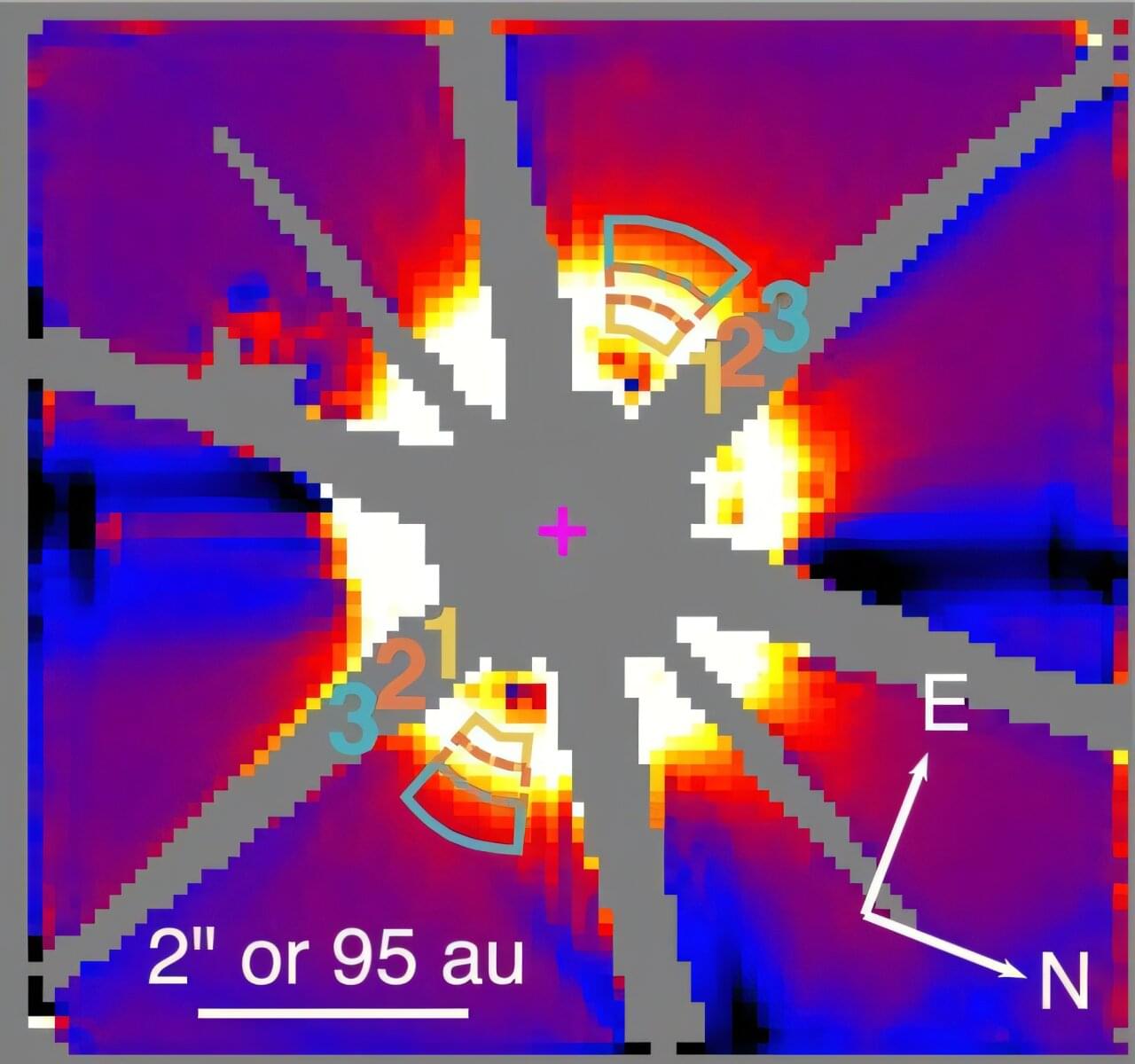

Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers from Johns Hopkins University (JHU) and elsewhere have detected water ice in a debris disk around HD 181327—a young star located within 160 light years away from the Earth. The finding was reported in a paper published May 14 in the journal Nature.

Debris disks are collections of small bodies around stars, including asteroids, Kuiper belt objects, comets, and also micron-sized debris dust. Observations of debris disks could help us better understand the evolution of planetary systems, the composition of dust, comets, and planetesimals outside our solar system.

Given that water plays a key role in the formation of planets and minor bodies, astronomers look for its presence also in debris disks. However, although water ice has been commonly detected in Kuiper belt objects and comets in the solar system, no definitive evidence for water ice in extrasolar debris disks has been found to date.