Extract from “Evolution, Basal Cognition and Regenerative Medicine”, kindly contributed by Michael Levin in SEMF’s 2023 Interdisciplinary Summer School (http…

Category: evolution – Page 22

Mammal’s lifespans linked to brain size and immune system function, says new study

So size does matter?

Mammal’s lifespans linked to brain size and immune system function, says new study.

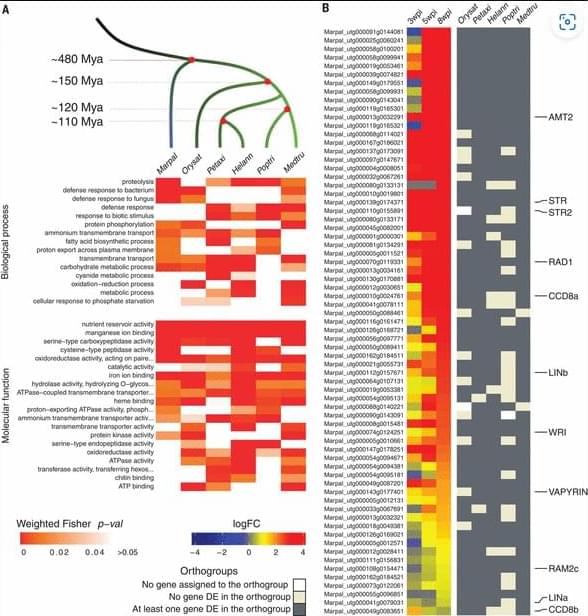

The researchers looked at the maximum lifespan potential of 46 species of mammals and mapped the genes shared across these species. The maximum lifespan potential (MLSP) is the longest ever recorded lifespan of a species, rather than the average lifespan, which is affected by factors such as predation and availability of food and other resources.

The researchers, publishing in the journal Scientific Reports, found that longer-lived species had a greater number of genes belonging to the gene families connected to the immune system, suggesting this as a major mechanism driving the evolution of longer lifespans across mammals.

For example, dolphins and whales, with relatively large brains have maximum lifespans of 39 and up to 100 years respectively, those with smaller brains like mice, may only live one or two years.

However, there were some species, such as mole rats, that bucked this trend, living up to 20 years despite their smaller brains. Bats also lived longer than would be expected given their small brains, but when their genomes were analysed, both these species had more genes associated with the immune system.

The results suggest that the immune system is central to sustaining longer life, probably by removing aging and damaged cells, controlling infections and preventing tumour formation.

Rare silver decay offers scientists a new window into the antineutrino’s elusive mass

Neutrinos and antineutrinos are elementary particles with small but unknown mass. High-precision atomic mass measurements at the Accelerator Laboratory of the University of Jyväskylä, Finland, have revealed that beta decay of the silver-110 isomer has a strong potential to be used for the determination of electron antineutrino mass. The result is an important step in paving the way for future antineutrino experiments.

The mass of neutrinos and their antineutrinos is one of the big unanswered questions in physics. Neutrinos are elementary particles in the Standard Model of particle physics and are very common in nature. They are produced, for example, by nuclear reactions in the sun. Every second, trillions of solar neutrinos travel through us.

“Their mass determination would be of utmost importance,” says Professor Anu Kankainen from the University of Jyväskylä. “Understanding them can give us a better picture of the evolution of the universe.”

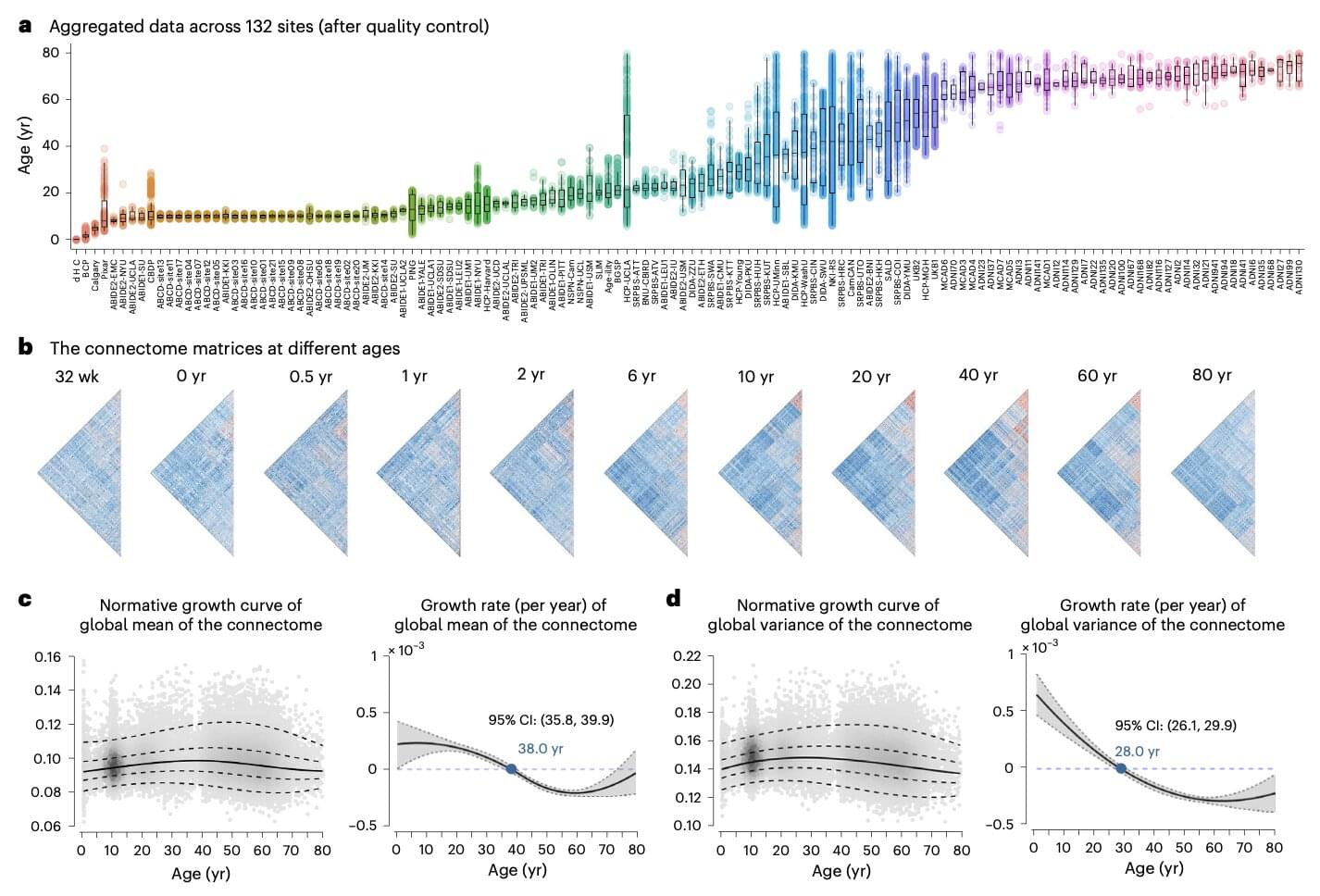

Large-scale study explores lifespan changes in the human brain’s functional connectivity

From birth to the last moments of life, the human brain is known to change and evolve significantly, both in terms of its physical organization (i.e., structural connectivity) and the coordination between different brain regions (i.e., functional connectivity). Mapping and understanding the brain’s evolution over time is of crucial importance, as it could also shed light on differences in the brains of individuals who develop various mental health disorders or experience an aging-related cognitive decline.

Researchers at Beijing Normal University and other institutes in China recently carried out a large-scale study to gather new insights into how the brain’s functional connectivity of humans worldwide changes over the course of their lifespan. Their paper, published in Nature Neuroscience, unveils patterns in the evolution of the brain that could inform future research focusing on a wide range of neuropsychiatric and cognitive disorders.

“Functional connectivity of the human brain changes through life,” wrote Lianglong Sun, Tengda Zhao and their colleagues in their paper. “We assemble task-free functional and structural magnetic resonance imaging data from 33,250 individuals at 32 weeks of postmenstrual age to 80 years from 132 global sites.”

Why ‘Evolving’ Dark Energy Worries Some Physicists

In 2024 a shockwave rippled through the astronomical world, shaking it to the core. The disturbance didn’t come from some astral disaster at the solar system’s doorstep, however. Rather it arrived via the careful analysis of many far-distant galaxies, which revealed new details of the universe’s evolution across eons of cosmic history. Against most experts’ expectations, the result suggested that dark energy —the mysterious force driving the universe’s accelerating expansion—was not an unwavering constant but rather a more fickle beast that was weakening over time.

The shocking claim’s source was the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI), run by an international collaboration at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona. And it was so surprising because cosmologists’ best explanations for the universe’s observed large-scale structure have long assumed that dark energy is a simple, steady thing. But as Joshua Frieman, a physicist at the University of Chicago, says: “We tend to stick with the simplest theory that works—until it doesn’t.” Heady with delight and confusion, theorists began scrambling to explain DESI’s findings and resurfaced old, more complex ideas shelved decades ago.

In March 2025 even more evidence accrued in favor of dark energy’s dynamic nature in DESI’s latest data release—this time from a much larger, multimillion-galaxy sample. Dark energy’s implied fading, it seemed, was refusing to fade away.

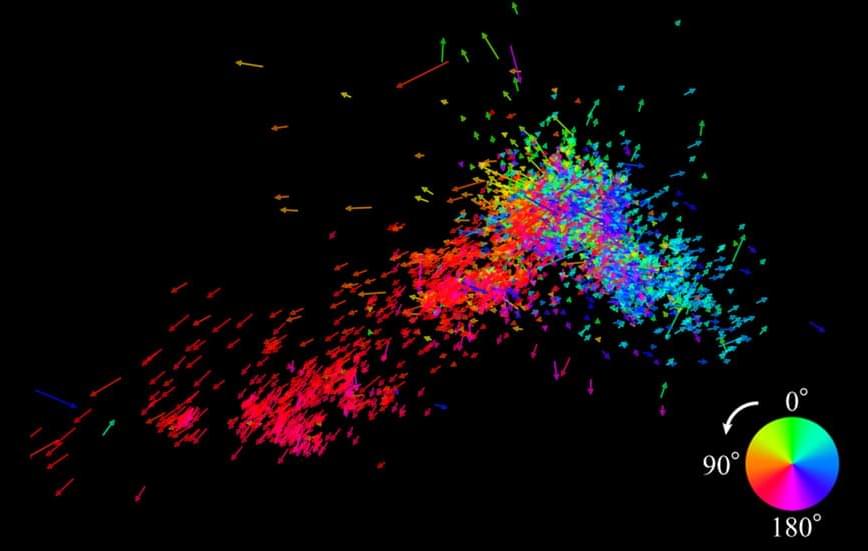

Our closest neighboring galaxy may be being torn apart

Is the nearest galaxy to ours being torn apart? Research suggests so. A team led by Satoya Nakano and Kengo Tachihara at Nagoya University in Japan has revealed new insights into the motion of massive stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC), a small galaxy neighboring the Milky Way. Their findings suggest that the gravitational pull of the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), the SMC’s larger companion, may be tearing the smaller one apart. This discovery reveals a new pattern in the motion of these stars that could transform our understanding of galaxy evolution and interactions. The results were published in The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series.

“When we first got this result, we suspected that there might be an error in our method of analysis,” Tachihara said. “However, upon closer examination, the results are indisputable, and we were surprised.”

The SMC remains one of the closest galaxies to the Milky Way. This proximity allowed the research team to identify and track approximately 7,000 massive stars within the galaxy. These stars, which are over eight times the mass of our Sun, typically survive for only a few million years before exploding as supernovae. Their presence indicates regions rich in hydrogen gas, a crucial component of star formation.