Replacing Aging — Dr. Jean M. Hebert, Ph.D. Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Dr. Jean M. Hebert, Ph.D. (https://einsteinmed.org/faculty/9069/jean-hebert/) is Professor in the Department of Genetics and in the Dominick P. Purpura Department of Neuroscience, at Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

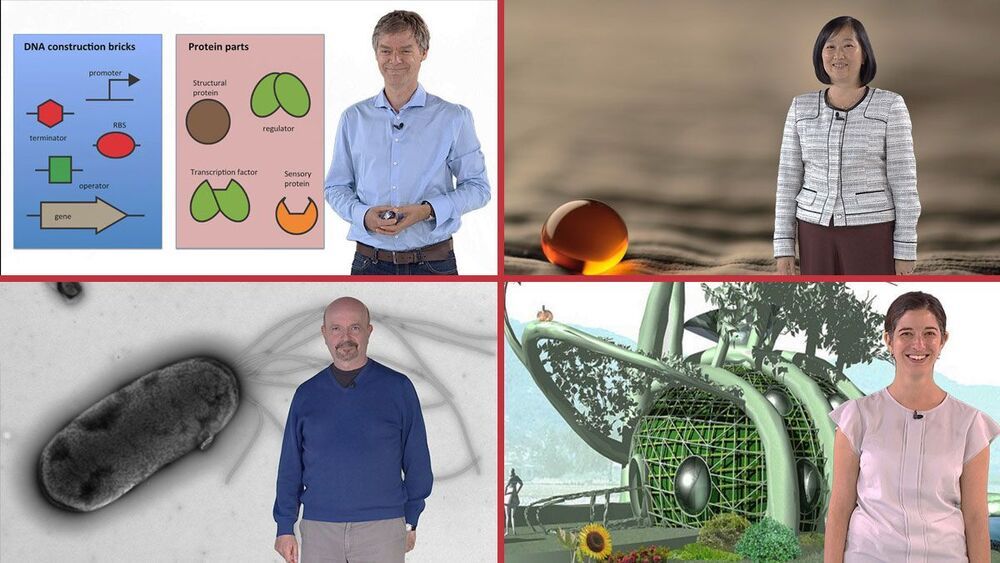

He’s also the author of the book Replacing Aging, which describes how regenerative medicine will beat aging.

With a Ph.D. in Genetics from the University of California, San Francisco, Dr. Hebert’s current lab’s projects fall into two groups.

First, they focus on using the mouse neocortex as a platform for testing the ability of multi-cell type grafts (increasingly resembling normal neocortex) to integrate with host tissue.