Category: alien life – Page 93

Humanity Will Need to Survive About 400,000 Years if We Want any Chance of Hearing From an Alien Civilization

Can humanity last another 400,000 years? We might have to if we want to talk to another technological civilization.

If there are so many galaxies, stars, and planets, where are all the aliens, and why haven’t we heard from them? Those are the simple questions at the heart of the Fermi Paradox. In a new paper, a pair of researchers ask the next obvious question: how long will we have to survive to hear from another alien civilization?

Their answer? 400,000 years.

Humans are the Mind of the Cosmos to The Unnerving Origin of Technosignatures

This week’s “Heard in the Milky Way” offers audio and video talks and interviews with leading astronomers and astrophysicists that range from Would Data from an Alien Intelligence be Lethal for Us to Neal Stephenson on Sci-Fi, Space, Aliens, AI and the Future of Humanity to Is Alien Life Weirder than We Think, and much more. This new weekly feature, curated by The Daily Galaxy editorial staff, takes you on a journey with stories that change our knowledge of Planet Earth, our Galaxy, and the vast cosmos beyond.

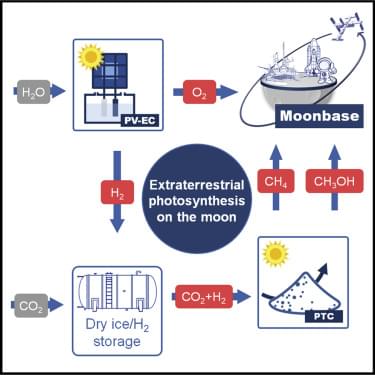

Extraterrestrial photosynthesis

“In light of significant efforts being taken toward manned deep space exploration, it is of high technological importance and scientific interest to develop the lunar life support system for long-term exploration. Lunar in situ resource utilization offers a great opportunity to provide the material basis of life support for lunar habitation and traveling. Based on the analysis of the structure and composition, Chang’E-5 lunar soil sample has the potential for lunar solar energy conversion, i.e., extraterrestrial photosynthetic catalysts. By evaluating the performance of the Chang’E-5 lunar sample as photovoltaic-driven electrocatalyst, photocatalyst, and photothermal catalyst, full water splitting and CO2 conversion are able to be achieved by solar energy, water, and lunar soil, with a range of target product for lunar life, including O2, H2, CH4, and CH3OH. Thus, we propose a potentially available extraterrestrial photosynthesis pathway on the moon, which will help us to achieve a “zero-energy consumption” extraterrestrial life support system.”

Chang’E-5 lunar soil was used as the lunar extraterrestrial photosynthetic catalyst for water splitting and CO2 conversion. Solar energy and water were converted into a wide range of valuable products for lunar life support, including O2, H2, CH4, and CH3OH. A “zero-energy consumption” extraterrestrial life support system was thus proposed.

Godlike Aliens

Visit https://brilliant.org/isaacarthur/ to get started learning STEM for free, and the first 200 people will get 20% off their annual premium subscription.

Science Fiction often shows us alien civilizations so advanced they are godlike, but how realistic are they, and what would such entities be like?

Biocene 2022 Registration: https://oai.org/biocene-2022-event-registration/

International Space Development Conference Registration: https://isdc2022.nss.org.

Visit our Website: http://www.isaacarthur.net.

Support us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/IsaacArthur.

Support us on Subscribestar: https://www.subscribestar.com/isaac-arthur.

Facebook Group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/1583992725237264/

Reddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/IsaacArthur/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Isaac_A_Arthur on Twitter and RT our future content.

SFIA Discord Server: https://discord.gg/53GAShE

Listen or Download the audio of this episode from Soundcloud: Episode’s Audio-only version: https://soundcloud.com/isaac-arthur-148927746/godlike-aliens.

Episode’s Narration-only version: https://soundcloud.com/isaac-arthur-148927746/godlike-aliens-narration-only.

Credits:

Alien Civilizations: Godlike Aliens.

Science & Futurism with Isaac Arthur.

Episode 341, May 5, 2022

Written, Produced & Narrated by Isaac Arthur.

Editors:

Andrew Nelson.

Curt Hartung.

David McFarlane.

Cover Art:

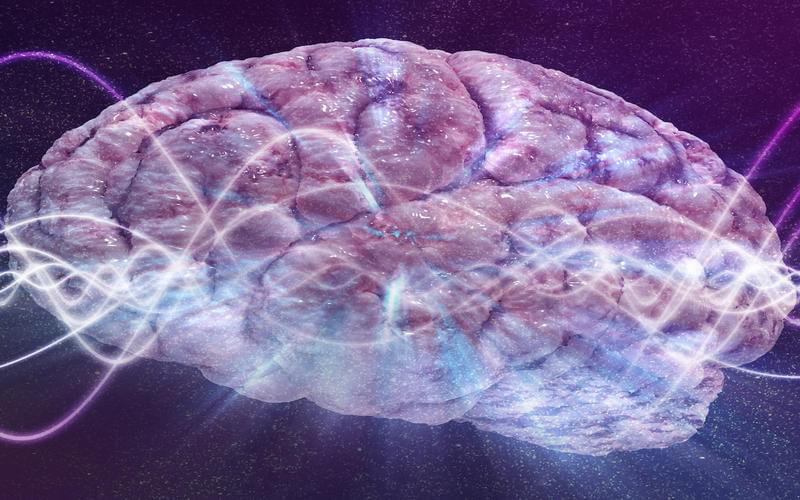

Consciousness is the collapse of the wave function

Consciousness defines our existence. It is, in a sense, all we really have, all we really are, The nature of consciousness has been pondered in many ways, in many cultures, for many years. But we still can’t quite fathom it.

Consciousness Cannot Have Evolved Read more Consciousness is, some say, all-encompassing, comprising reality itself, the material world a mere illusion. Others say consciousness is the illusion, without any real sense of phenomenal experience, or conscious control. According to this view we are, as TH Huxley bleakly said, ‘merely helpless spectators, along for the ride’. Then, there are those who see the brain as a computer. Brain functions have historically been compared to contemporary information technologies, from the ancient Greek idea of memory as a ‘seal ring’ in wax, to telegraph switching circuits, holograms and computers. Neuroscientists, philosophers, and artificial intelligence (AI) proponents liken the brain to a complex computer of simple algorithmic neurons, connected by variable strength synapses. These processes may be suitable for non-conscious ‘auto-pilot’ functions, but can’t account for consciousness.

Finally there are those who take consciousness as fundamental, as connected somehow to the fine scale structure and physics of the universe. This includes, for example Roger Penrose’s view that consciousness is linked to the Objective Reduction process — the ‘collapse of the quantum wavefunction’ – an activity on the edge between quantum and classical realms. Some see such connections to fundamental physics as spiritual, as a connection to others, and to the universe, others see it as proof that consciousness is a fundamental feature of reality, one that developed long before life itself.

Alien Message to be Sent into Space

A radio message will be sent to an alien solar system this year. What should it say?And what are the pros and cons to sending interstellar messages to aliens that may or may not exist.

See my blog on BigThink.com.

Link to go directly to the article.

This blog was posted on Big Think.