Category: alien life – Page 57

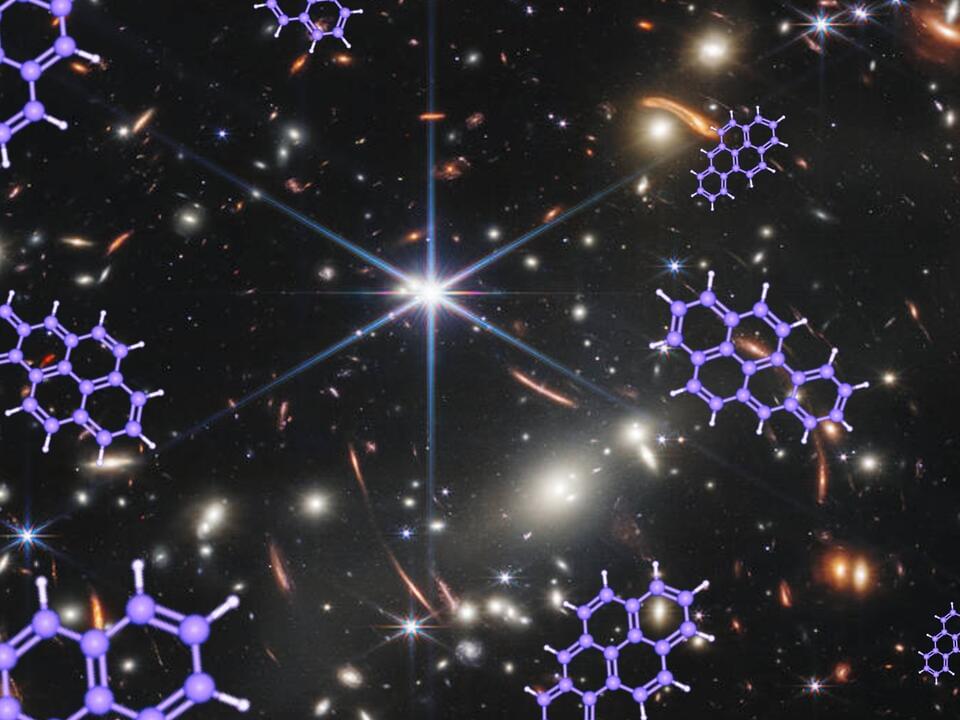

James Webb Space Telescope makes 1st detection of diamond-like carbon dust in the universe’s earliest stars

The James Webb Space Telescope has detected the earliest-known carbon dust in a galaxy ever.

Using the powerful space telescope, a team of astronomers spotted signs of the element that forms the backbone of all life in ten different galaxies that existed as early as 1 billion years after the Big Bang.

The detection of carbon dust so soon after the Big Bang could shake up theories surrounding the chemical evolution of the universe. This is because the processes that create and disperse heavier elements like this should take longer to build up in galaxies than the age of these young galaxies at the time the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) sees them.

Ammonia-Based Lifeforms

Get a free bag of fresh coffee with any Trade subscription at https://www.drinktrade.com/isaacarthur.

Our search for extraterrestrial life assumes alien life based on water and carbon, but could there be biochemistries based on other substances?

NSS Townhall Registration & Q&A Submission: https://space.nss.org/nss-town-hall-july-20-with-nss-senior-leadership/

Visit our Website: http://www.isaacarthur.net.

Checkout this episode ad-free on Nebula: https://nebula.tv/videos/isaacarthur-ammonia-based-lifeforms.

Support us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/IsaacArthur.

Support us on Subscribestar: https://www.subscribestar.com/isaac-arthur.

Facebook Group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/1583992725237264/

Reddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/IsaacArthur/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Isaac_A_Arthur on Twitter and RT our future content.

SFIA Discord Server: https://discord.gg/53GAShE

Listen or Download the audio of this episode from Soundcloud: Episode’s Audio-only version: https://soundcloud.com/isaac-arthur-148927746/ammonia-based-lifeforms.

Episode’s Narration-only version: https://soundcloud.com/isaac-arthur-148927746/ammonia-based-…ation-only.

Credits:

Ammonia-Based Lifeforms.

Episode 404, July 20, 2023

Written, Produced & Narrated by:

Isaac Arthur.

Editors:

Is there life on Venus? Report confirms more phosphine

(NewsNation) — Astronomers have once again found a potential signal of life in the clouds of Venus.

The controversial observation of molecules of phosphine was first reported in 2020. Phosphine, comprised of hydrogen and phosphorus, is a gas on Earth that is only associated with life.

Three years later, “extensive additional detections” of the molecules were presented at the National Astronomy Meeting 2023 at Cardiff University in Wales, UK, according to a Forbes report.

‘Hundred times’ more probability of finding water on exoplanets, says new study

Rutgers University scientists believe there might be many more Earth-like exoplanets with liquid water.

Are we alone in this vast universe? Are there planets out there that harbor liquid water and ideal conditions for life to thrive?

These are some of the major questions that space scientists hope to find answers to. However, in order to answer these big questions, it is necessary to get into the nitty-gritty of what may allow water to sustain itself on other distant planets.

NASA’s Juno Spacecraft Just Captured A Spooky Green Lightning Flash On Jupiter

NASA’s Juno spacecraft recently captured this spooky green flash of lightning in a massive storm swirling near Jupiter’s north pole.

The tremendous burst of lightning glows bright against the dark gray vortex of the storm, even from Juno’s vantage point 19,900 miles above the tops of Jupiter’s clouds. Lightning often flashes between the clouds of stormy Jupiter’s higher latitudes, especially in the north. NASA’s Juno spacecraft is helping shed light on the gas giant’s wild alien weather.

Citizen scientist Kevin M. Gill processed the image from Juno’s raw data.

Ariane 5 aces final launch, paving the way for debut of Ariane 6

And Europe currently has no operational rocket at its disposal.

Europe’s workhorse Ariane 5 rocket aced its final launch, as its maker Arianespace now looks ahead to the debut of its long-delayed Ariane 6. The Ariane 5 rocket took off from the European Spaceport at Kourou, French Guiana, at 6 p.m. ET, July 5. Arianespace and The European Space Agency (ESA) had originally intended for the final launch of Ariane 5 to take place after the debut of Ariane 6.

A long string of delays to Ariane 6, however, means that Europe currently has no operational rocket, and it likely won’t have one until next year.

ESA

The Ariane 5 rocket took off from the European Spaceport at Kourou, French Guiana, at 6 p.m. ET, July 5. Arianespace and The European Space Agency (ESA) had originally intended for the final launch of Ariane 5 to take place after the debut of Ariane 6.

The Golden Age of Space Exploration

In the next two decades, human beings will return to the moon, set foot on Mars, and launch telescopes capable of detecting extraterrestrial life. NASA’s outgoing head scientist Thomas Zurbuchen oversaw much of the planning for these projects, and space agencies around the world are pursuing similar goals collaboratively. Brian Greene is joined by Zurbuchen, Japan’s Masaki Fujimoto, Europe’s Kirsten MacDonnell and Australia’s Aude Vignelles, as they reveal their plans for what promises to be a New Golden Age of Space Exploration.

This program is part of the Big Ideas series, supported by the John Templeton Foundation.

The live program was presented at the 2023 World Science Festival Brisbane, hosted by the Queensland Museum.

Participants:

Masaki Fujimoto.

Kirsten MacDonell.

Aude Vignelles.

Thomas Zurbuchen.

Moderator:

Brian Greene.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS on this program through a short survey: