It’s been awhile since the cost of gasoline topped $4 in the U.S. The national average hit $4.11 on July 11, 2008 and came close in May 2011 at $3.96. On New Years Day 2015, I drove through the night from Chicago to Boston. Despite the cold weather, the economics of fuel made it the best day for a road trip in years. I bought gas at a Pilot service station just off the Ohio Turnpike at $1.92/gallon. For me, it seemed like a bargain. Yet, 23 states charge less for gasoline than Ohio.

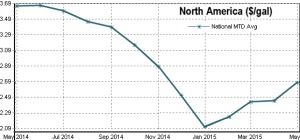

Now, at the end of May 2015, gas is rebounding from that low. Drivers on Memorial Day weekend faced the highest cost for gasoline of the year so far.

It’s tempting for politicians to advocate using tax breaks to smooth price spikes. With energy often surpassing the expense of food and rent and with so many individuals using fuel to make a living, reducing user fees or taxes during periods of very high fuel cost seems like the humane thing to do.

It seems humane, but it has the opposite effect. In fact, it is deeply punitive! That’s because the cost of gas is not an act of nature, nor even of free market economics. It is a product of cartels, special interests, conflict and FUD (fear, uncertainty and doubt). Offering relief during price spikes sustains demand while doing absolutely nothing to increase supply. This, in turn, exacerbates the spike, creates shortages for critical services and transfers enormous sums of money from consumers to producers. In effect, it is a free gift for producer nations.

In fact, consumers and consuming nations are best served by a raising taxes in lockstep with fuel price increases.

In May 2011, as gas prices were spiking to an all time high, a group calling itself National Taxpayers Union or NTU launched a $1.25 million campaign to fight energy taxes, like the fuel tax added to the cost of gasoline at the pump in most countries.* One of the group’s less controversial public service announcements (or more accurately, a lobbying effort) consist of magazine ads and videos that encourage Americans to write their legislators and demand a roll back of gas taxes whenever market prices spike.

I hate consumption taxes, especially the ones that target individual commodities or categories, such as alcohol, cigarettes, luxury purchases, or any system of import tariffs. They are a form of social engineering and they bastardize free markets. But when an energy consumer nation gives consumers breaks during periods of price spikes, the result counters the social intent. In fact, each time that oil prices rise, the best thing our government can do is to force them higher still! This may sound crazy, but when the supply of a commodity is controlled a few foreign cartels, it is no longer a commodity. Artificially lowering the consumer price by subsidizing the price simply stimulates consumption. It does not expand supply, and so the subsidy goes directly into suppliers’ pockets.

Apparently, I am not the only one who thinks that lower gas prices is a bad idea. Folling the 2011 gas spike (the highest cost gas spike in U.S. history), Motley Fool columnist, Travis Hoium filed an Op-Ed entitled, 3 Reasons the US Should Want Higher Oil Prices. (At the same time, I cautioned against tax relief tied to gasoline price hikes). His analysis and opinion is articulate and adequately supported, but none of his reasons point to the fundamental economic reason that for a country that aspires to energy independence, oil should be taxed higher whenever the market cost of externally sourced oil rises. Let me spell it out…

What happens if we lower the cost of a commodity to consumers in an effort to counteract a higher supply price? It doesn’t take an Economist to analyze. Since the supply is not increased, throwing a subsidy to the buyers “fuels” an even faster rise in prices and hands all that money to the supplier.

Let’s say that C = Amount of fuel needed for critical purposes

…getting to work, heating our home, manufacturing

Let’s say that D = Amount of fuel needed for discretionary purposes

…vacation travel, backyard BBQ, mowing the lawn, etc

Of course, with a limited personal budget, high fuel prices influence a consumer’s decision to classify an activity as ‘critical’ or ‘discretionary’. Additionally, the use of fuel is greatly affected by how efficiently you perform a task (taking a train to work instead of driving, vacationing nearby instead of far away, etc).

Foreign cartels wish to maintain high prices and high revenue, so they limit the foreign supply of oil. For them, it makes more sense to charge a lot of money for less product than to charge less money for a lot of product. If we consider again our classification of consumption into two categories, Critical and Discretionary, the supplier limits leave us with only enough fuel to support this much activity:

100%C + 80%(D)

Now if we counteract their production limits and insulate consumers from the higher cost, the formula doesn’t change. We continue to use just as much fuel.

In a free market, limited supply causes prices to rise and this forces consumers to cut back on discretionary use. Some consumers with less money must cut back on critical needs. That’s because some people can afford the keep buying and of course the cost of fuel rises.

In a free market — at least on our side of the ocean, this normally leads to several things — all of them very good:

• Increase exploration and domestic production (Motley Fool covers this one)

• Develop alternative fuels, especially domestic and environmentally friendly

• Increase conservation:

- Reduce travel

- Turn off unnecessary appliances

- Turn down heat, insulating home or office

• Change modalities:

- Carpool or use public transportation

- Reclassify some “Critical” uses as “Discretionary”

- Buy local (reduces wholesale transportation)

- Switch electric providers to avoid foreign sources

If consumers are suddenly subsidized when the cost of fuel rises, something terrible happens. Instead of producing more domestic energy, we are not at all affecting the supply. We are simply handing the foreign seller more cash — directly from the taxpayer to their pockets. And they didn’t even ask for it! They raise the cost by $1 per gallon and we give them $2 extra. Heck, why not? It makes us feel good.

What happens if we increase taxes when suppliers raise prices? First, we benefit by all the good things listed above.

Second, since some foreign suppliers are not truly constrained in their production (that is, they have plenty of oil), they will keep costs low in order to sustain revenue. There are plenty of places this “cost reduction” tax can be inserted: at point-of-sale, at import, or in the distribution chain.

What do we do with the money that is raised by taxes? That’s easy too. Give it back to consumers or use it to fund the development of energy sources that are domestic, inexpensive and environmentally safe.

This is how supply and demand should work. Of course, the government can still subsidize those in need. But do it in a way that doesn’t bastardize market dynamics. As a society, we provide assistance to the consumers who cannot afford energy for critical needs, and not by handing money to the supplier (effectively, a reward for cutting production). In this way, we reduce consumption, increase domestic production and provide direct assistance to those who are less fortunate. The effect of subsidizing some buyers will force some other buyers to reduce discretionary use. For example, if some of the higher cost went to taxes, it could be used to help ease the consumers who can no longer afford the “critical” fraction of their use.

_____________

* Americans are taxed for automotive fuel at the pump: A federal tax of 18.4¢ plus a state tax that varies between 12~35¢. The average state tax is about 23¢/gal, so the typical American pays about 41½¢ tax on each gallon, or approximately 10%.

Philip Raymond is Co-Chair of The Cryptocurrency Standards Association and CEO of Vanquish Labs.

An earlier draft of this article was published in his Blog.