Transistors are fundamental to microchips and modern electronics. Invented by Bardeen and Brattain in 1947, their development is one of the 20th century’s key scientific milestones. Transistors work by controlling electric current using an electric field, which requires semiconductors. Unlike metals, semiconductors have fewer free electrons and an energy band gap that makes it harder to excite electrons.

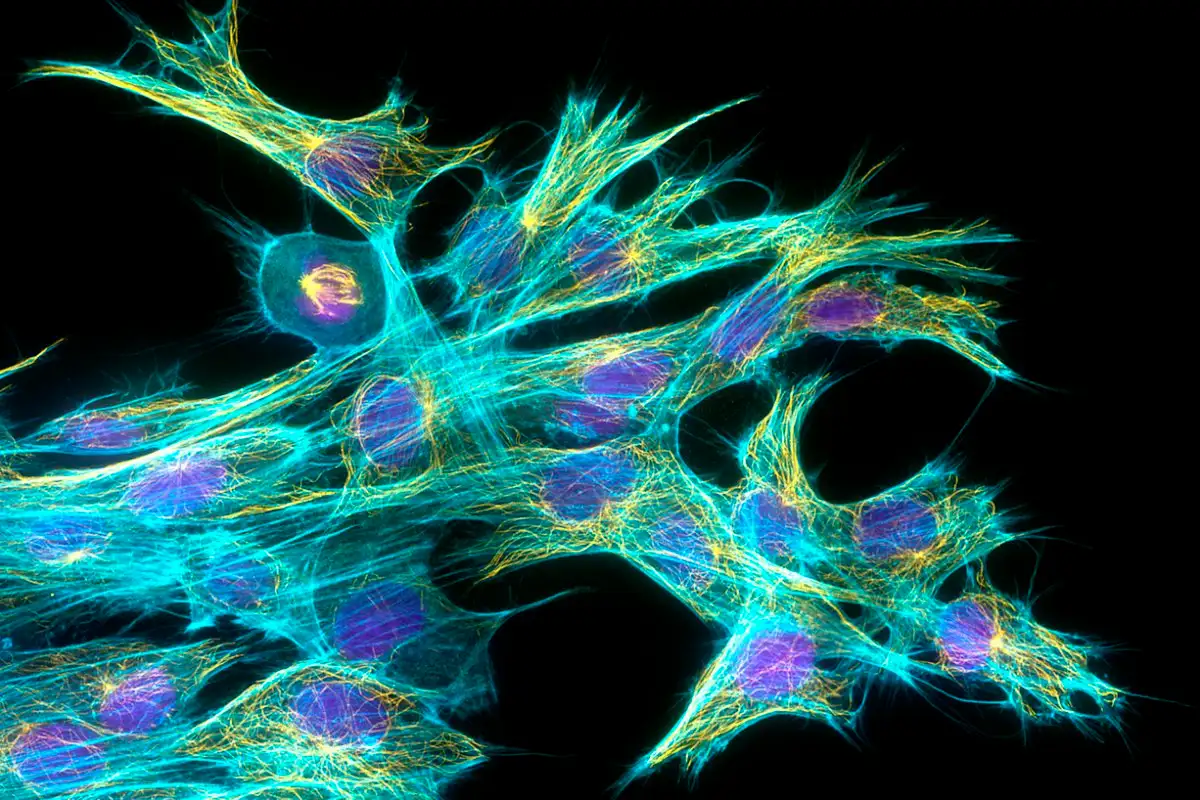

Doping introduces charge carriers, enabling current flow under an electric field. This allows for nonlinear current-voltage behavior, making signal amplification or switching possible, as in p–n junctions. Metals, by contrast, have too many free electrons that quickly redistribute to cancel external fields, preventing controlled current flow—hence, they can’t be used as traditional transistors.

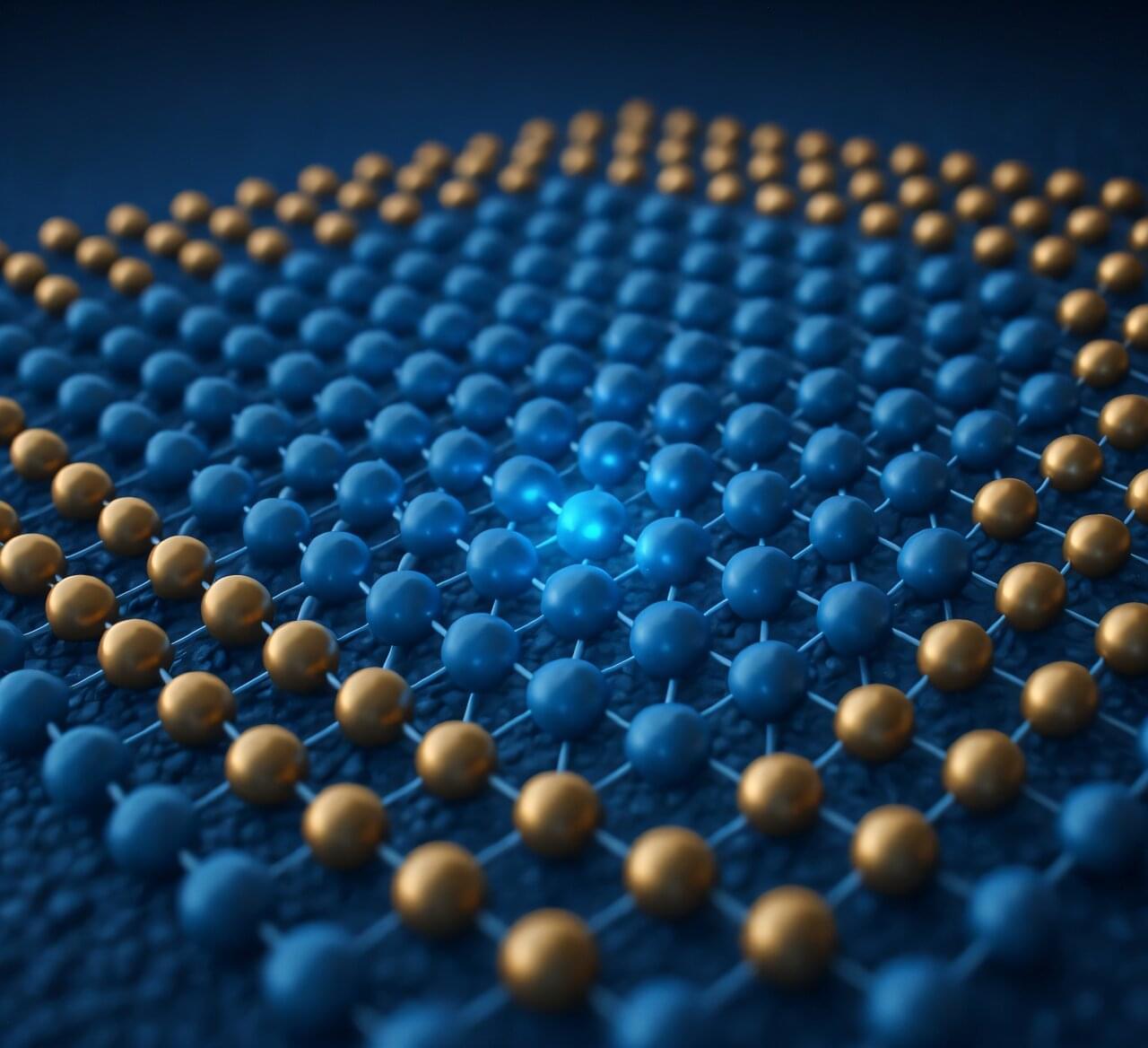

However, recent advances show promise in ultrathin superconducting metals as potential transistor materials. When cooled below a critical temperature, these materials carry current with zero resistance. This behavior arises from the formation of Cooper pairs—electrons bound by lattice vibrations—that condense into a coherent quantum state, immune to scattering and energy loss.