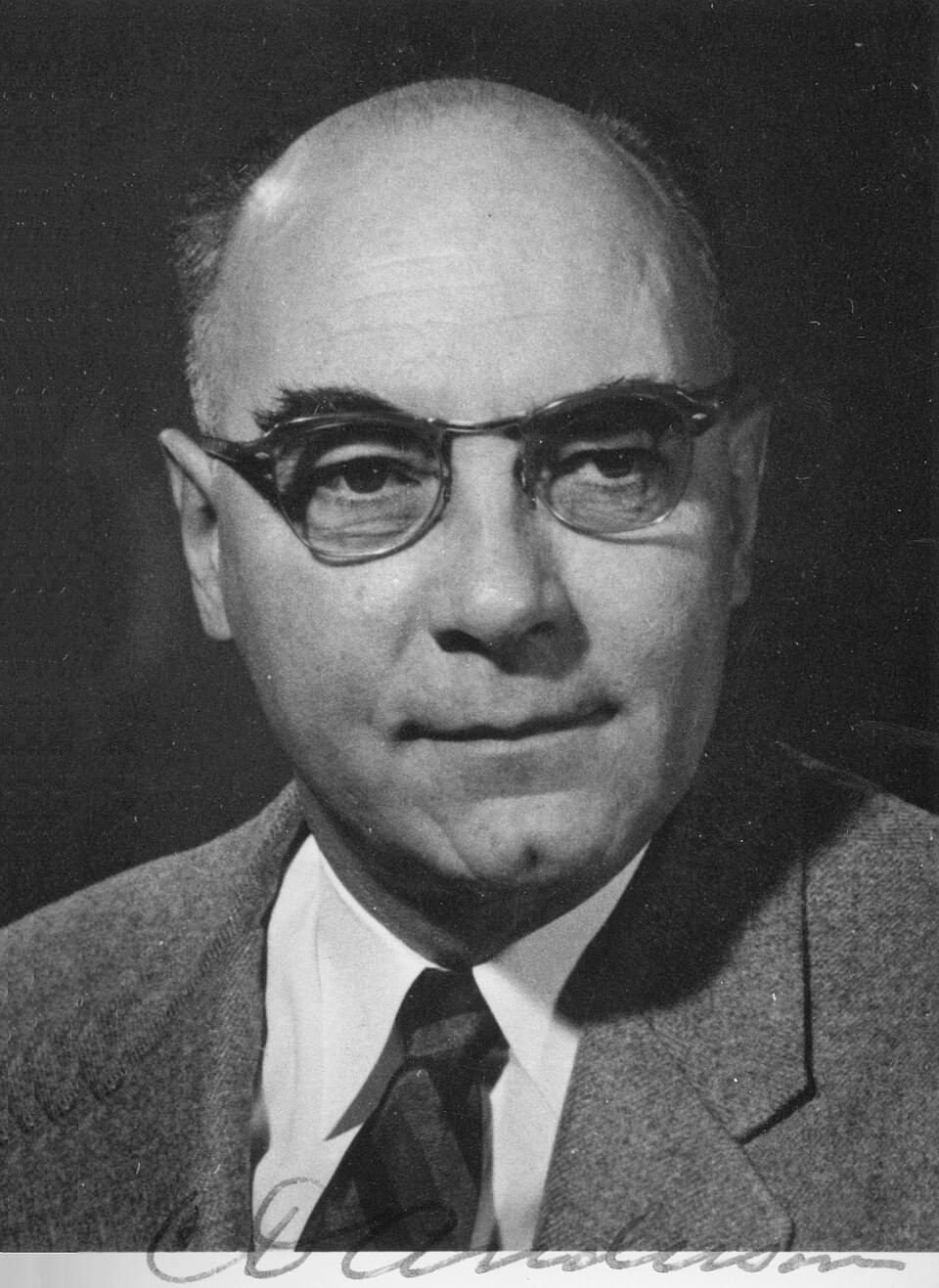

Carl David Anderson was born in New York City, the son of Swedish immigrants. He studied physics and engineering at Caltech (B.S., 1927; Ph. D., 1930). Under the supervision of Robert Millikan, He began investigations into cosmic rays during the course of which he encountered unexpected particle tracks in his (modern versions now commonly referred to as an Anderson) cloud chamber photographs that he correctly interpreted as having been created by a particle with the same mass as the electron, but with opposite electrical charge. This discovery, announced in 1932 and later confirmed by others, validated Paul Dirac’s theoretical prediction of the existence of the positron. Anderson first detected the particles in cosmic rays. He then produced more conclusive proof by shooting gamma rays produced by the natural radioactive nuclide ThC’’ (208 Tl) [ 2 ] into other materials, resulting in the creation of positron-electron pairs. For this work, Anderson shared the 1936 Nobel Prize in Physics with Victor Hess. [ 3 ] Fifty years later, Anderson acknowledged that his discovery was inspired by the work of his Caltech classmate Chung-Yao Chao, whose research formed the foundation from which much of Anderson’s work developed but was not credited at the time. [ 4 ]

Also in 1936, Anderson and his first graduate student, Seth Neddermeyer, discovered a muon (or ‘mu-meson’, as it was known for many years), a subatomic particle 207 times more massive than the electron, but with the same negative electric charge and spin 1/2 as the electron, again in cosmic rays. Anderson and Neddermeyer at first believed that they had seen a pion, a particle which Hideki Yukawa had postulated in his theory of the strong interaction. When it became clear that what Anderson had seen was not the pion, the physicist I. I. Rabi, puzzled as to how the unexpected discovery could fit into any logical scheme of particle physics, quizzically asked “Who ordered that?” (sometimes the story goes that he was dining with colleagues at a Chinese restaurant at the time). The muon was the first of a long list of subatomic particles whose discovery initially baffled theoreticians who could not make the confusing “zoo” fit into some tidy conceptual scheme.