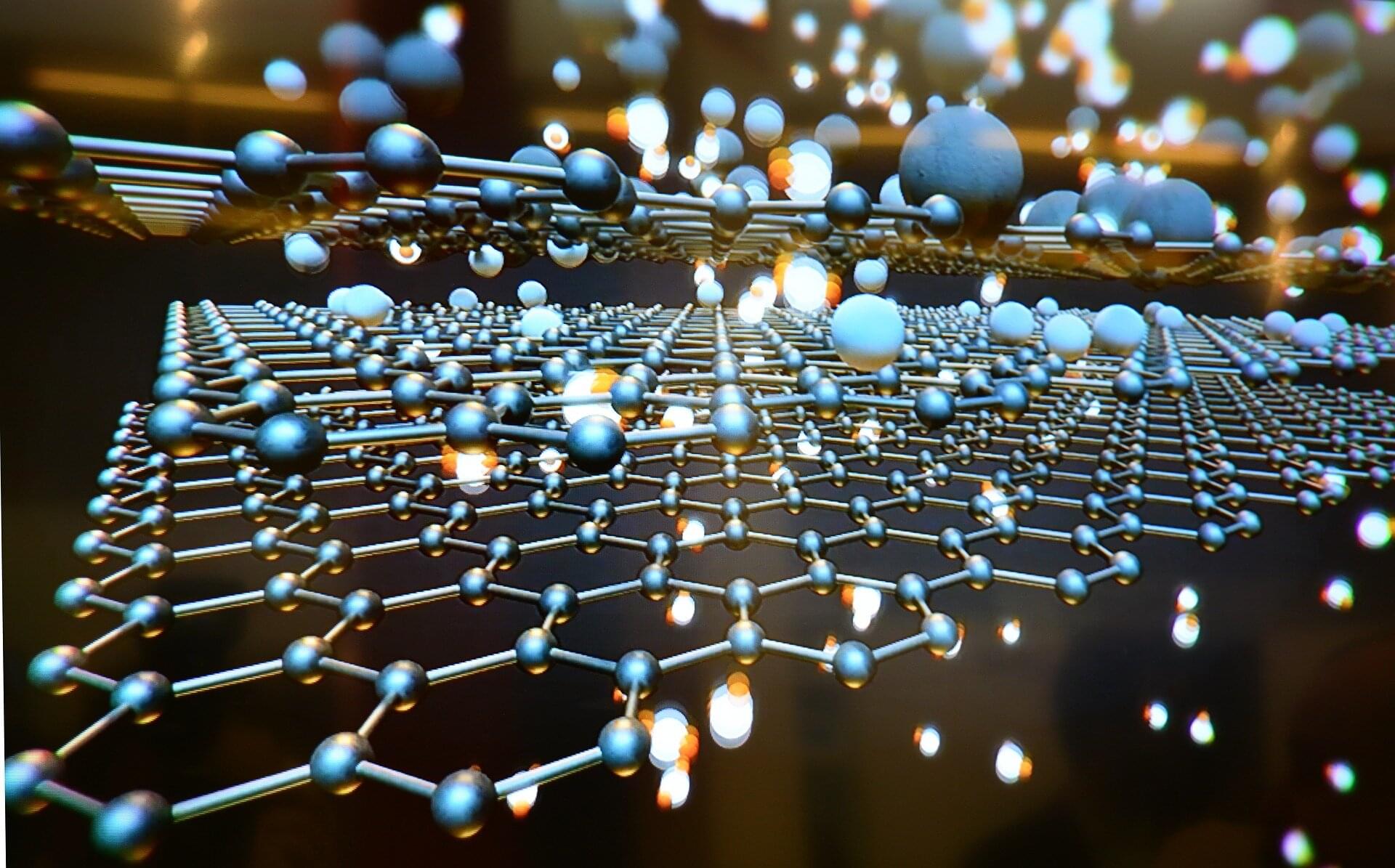

A new climate modeling study published in the journal Science Advances by researchers from the IBS Center for Climate Physics (ICCP) at Pusan National University in South Korea presents a new scenario of how climate and life on our planet would change in response to a potential future strike of a medium-sized (~500 m) asteroid.

The solar system is full of objects with near-Earth orbits. Most of them do not pose any threat to Earth, but some of them have been identified as objects of interest with non-negligible collision probabilities. Among them is the asteroid Bennu with a diameter of about 500 m, which—according to recent studies—has an estimated chance of 1 in 2700 of colliding with Earth in September 2182. This is similar to the probability of flipping a coin 11 times in a row with the same outcome.

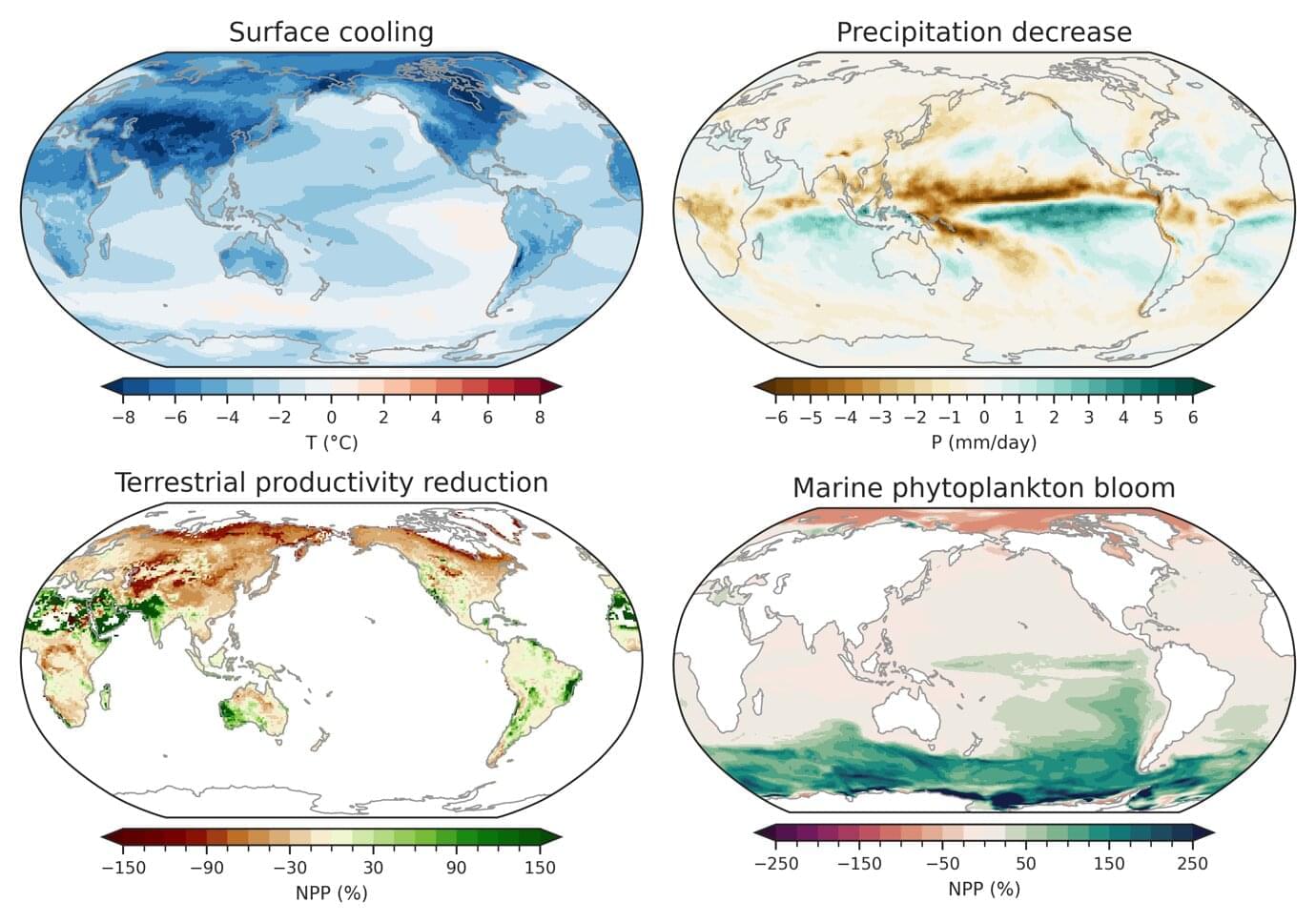

To determine the potential impacts of an asteroid strike on our climate system and on terrestrial plants and plankton in the ocean, researchers from the ICCP set out to simulate an idealized collision scenario with a medium-sized asteroid using a state-of-the-art climate model.