(MENAFN — The Conversation) A large crack, stretching several kilometres, made a sudden appearance recently in south-western Kenya. The tear, which continues to grow, caused part of the Nairobi-Narok highway to collapse. Initially, the appearance of the crack was linked to tectonic activity along the East African Rift. But although geologists now think that this feature is most likely an erosional gully, questions remain as to why it has formed in the location that it did and whether its appearance is at all connected to the ongoing East African Rift. For example, the crack could be the result of the erosion of soft soils infilling an old rift-related fault.

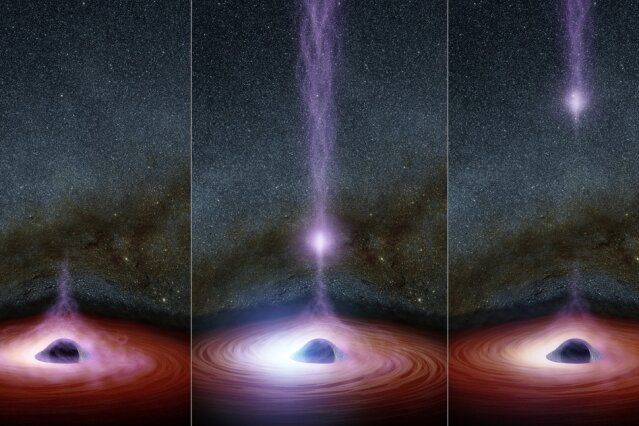

The Earth is an ever-changing planet, even though in some respects change might be almost unnoticeable to us. Plate tectonics is a good example of this. But every now and again something dramatic happens and leads to renewed questions about the African continent splitting in two.

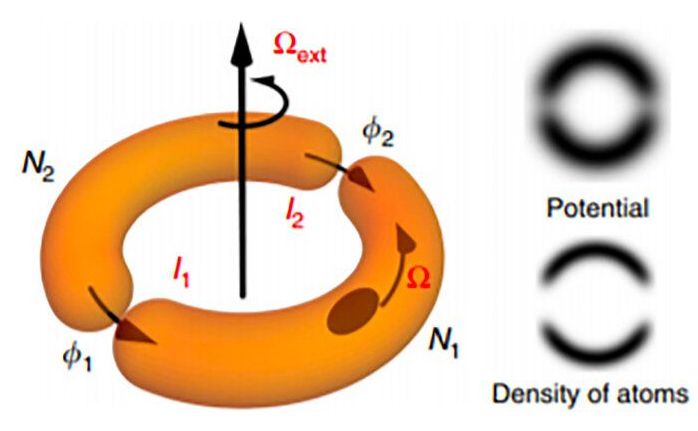

The Earth’s lithosphere (formed by the crust and the upper part of the mantle) is broken up into a number of tectonic plates. These plates are not static, but move relative to each other at varying speeds, ‘gliding’ over a viscous asthenosphere. Exactly what mechanism or mechanisms are behind their movement is still debated, but are likely to include convection currents within the asthenosphere and the forces generated at the boundaries between plates.