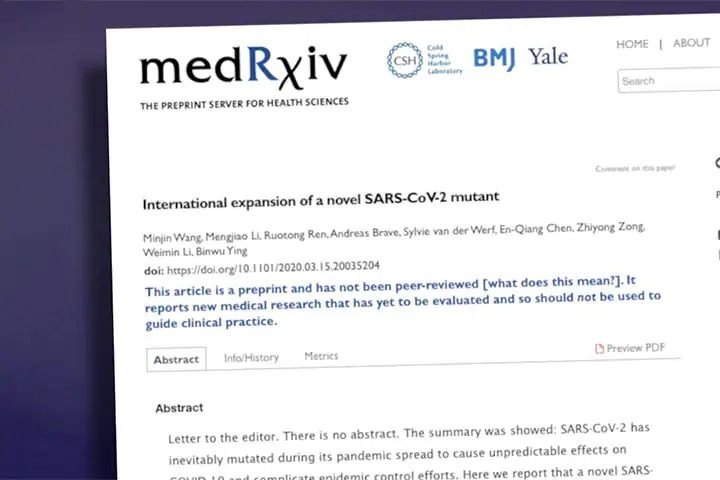

It appears that there are some effective treatments for COVID-19 rising up. These could dramatically improve/weaken the effects of the virus.

There’s also some hope that things are better than they seem anyway. There’s growing evidence that a lot of people have COVID-19 but have such mild symptoms that they aren’t being tested and counted as confirmed cases — which means the death rate and statistics about severe cases are much better than they seem. Additionally, it’s possible a larger share of the population is immune to the virus than initially thought:

There are plenty of things to consider with regards to the ongoing coronavirus COVID-19 crisis — dozens or hundreds of important matters. I am not a medical expert in any way, but like others, I’ve been compelled to obsessively read about this stuff and also see what rises to the top of social media and conventional media.

While much focus is put on the need for social distancing at this time and considering the best path forward economically (whether it’s this plan or this plan or this plan or one of these plans — I know, those are snapshots of plans or superficial ideas for plans), and while medical professionals work on vaccines that may be available in 14 months or so, other medical professionals have been focusing their attention on what works for softening the symptoms of COVID-19 or even turning a patient negative.

Again, I am not a medical professional, but a few promising stories have popped up that I thought I’d share. I look forward to responses down in the comments.