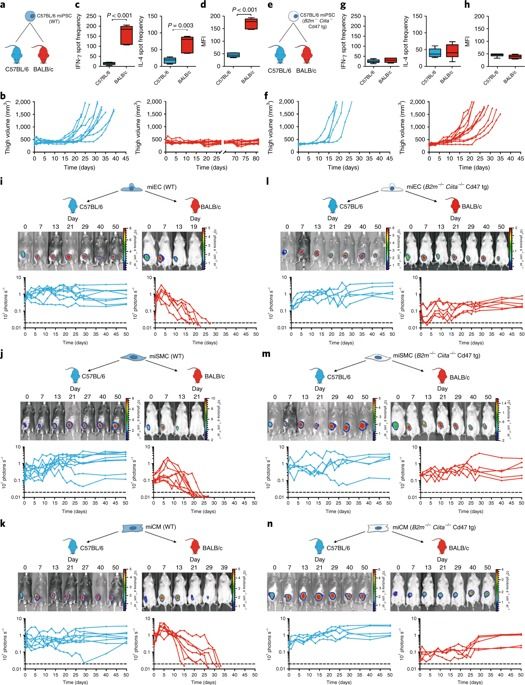

Autologous induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) constitute an unlimited cell source for patient-specific cell-based organ repair strategies. However, their generation and subsequent differentiation into specific cells or tissues entail cell line-specific manufacturing challenges and form a lengthy process that precludes acute treatment modalities. These shortcomings could be overcome by using prefabricated allogeneic cell or tissue products, but the vigorous immune response against histo-incompatible cells has prevented the successful implementation of this approach. Here we show that both mouse and human iPSCs lose their immunogenicity when major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II genes are inactivated and CD47 is over-expressed. These hypoimmunogenic iPSCs retain their pluripotent stem cell potential and differentiation capacity. Endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and cardiomyocytes derived from hypoimmunogenic mouse or human iPSCs reliably evade immune rejection in fully MHC-mismatched allogeneic recipients and survive long-term without the use of immunosuppression. These findings suggest that hypoimmunogenic cell grafts can be engineered for universal transplantation.

However, a shortage of hi-tech research capacity in the region is turning into a hindrance, according to analysts, with most of China’s top-notch science and engineering schools located in the northern and eastern provinces. Although Hong Kong has several universities in the world’s top 100, only a few of them have a science and technology focus.

China’s ‘Greater Bay Area’ plan aims to erase barriers between cities in the region in terms of policy, financing, logistics and talent.

Barely a week goes by without reports of some new mega-hack that’s exposed huge amounts of sensitive information, from people’s credit card details and health records to companies’ valuable intellectual property. The threat posed by cyberattacks is forcing governments, militaries, and businesses to explore more secure ways of transmitting information.

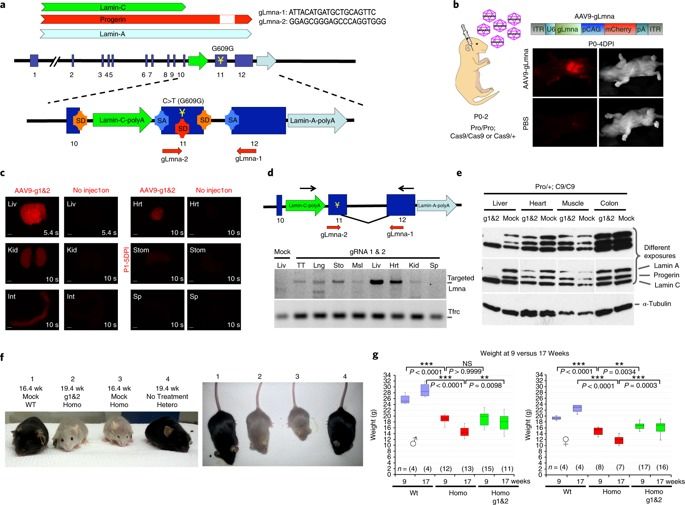

Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) is a rare lethal genetic disorder characterized by symptoms reminiscent of accelerated aging. The major underlying genetic cause is a substitution mutation in the gene coding for lamin A, causing the production of a toxic isoform called progerin. Here we show that reduction of lamin A/progerin by a single-dose systemic administration of adeno-associated virus-delivered CRISPR–Cas9 components suppresses HGPS in a mouse model.

It’s inevitable in life, but aging isn’t really something people look forward to. Researchers have been seeking ways to reduce the impact of aging, not only because of vanity but also because as we age, there is a greater risk of certain serious health conditions like cancer, heart disease and neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s disease. Salk Institute scientists have now used CRISPR/Cas9, the gene-editing tool, to slow down aging. The work, reported in Nature Medicine, showed accelerated aging can be slowed in mice modeling a rare genetic disorder called Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome.

“Aging is a complex process in which cells start to lose their functionality, so it is critical for us to find effective ways to study the molecular drivers of aging,” said the senior author of the report Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, a professor in Salk’s Gene Expression Laboratory. “Progeria is an ideal aging model because it allows us to devise an intervention, refine it and test it again quickly.”

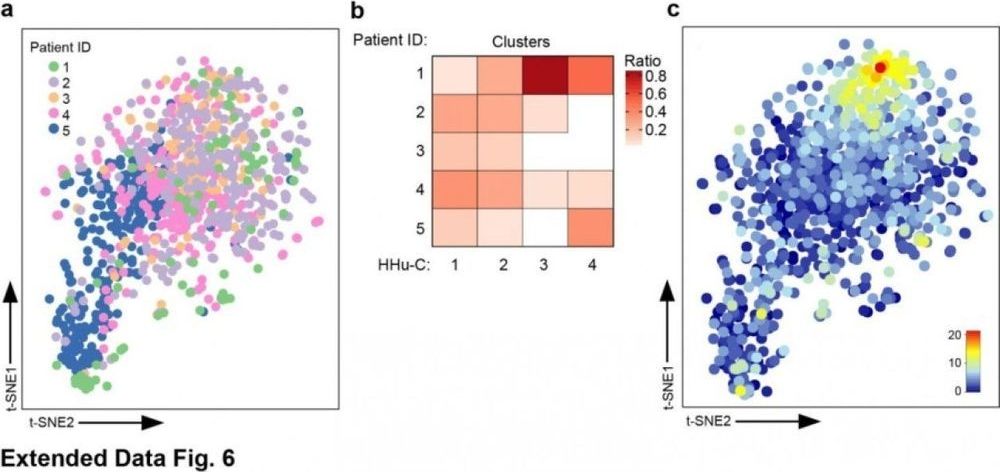

“We were able to show that there is only a single type of microglia in the brain that exist in multiple flavours,” says project head Prof. Dr. Marco Prinz, medical director of the Institute of Neuropathology at the Medical Center — University of Freiburg. “These immune cells are very versatile all-rounders, not specialists, as has been the textbook opinion up to now,” sums up Prof. Prinz.

A team of researchers under the direction of the Medical Center — University of Freiburg has created an entirely new map of the brain’s own immune system in humans and mice. The scientists succeeded in demonstrating for the first time ever that the phagocytes in the brain, the so-called microglia, all have the same core signature but adopt in different ways depending on their function. It was previously assumed that these are different types of microglia. The discovery, made by means of a new, high-resolution method for analyzing single cells, is important for the understanding of brain diseases. Furthermore, the researchers from Freiburg, Göttingen, Berlin, Bochum, Essen, and Ghent (Belgium) demonstrated in detail how the human immune system in the brain changes in the course of multiple sclerosis (MS), which is significant for future therapeutic approaches. The study was published on 14. February 2019 in the journal Nature.