The need to pivot from quaint reassurances to immersion in cosmic horror

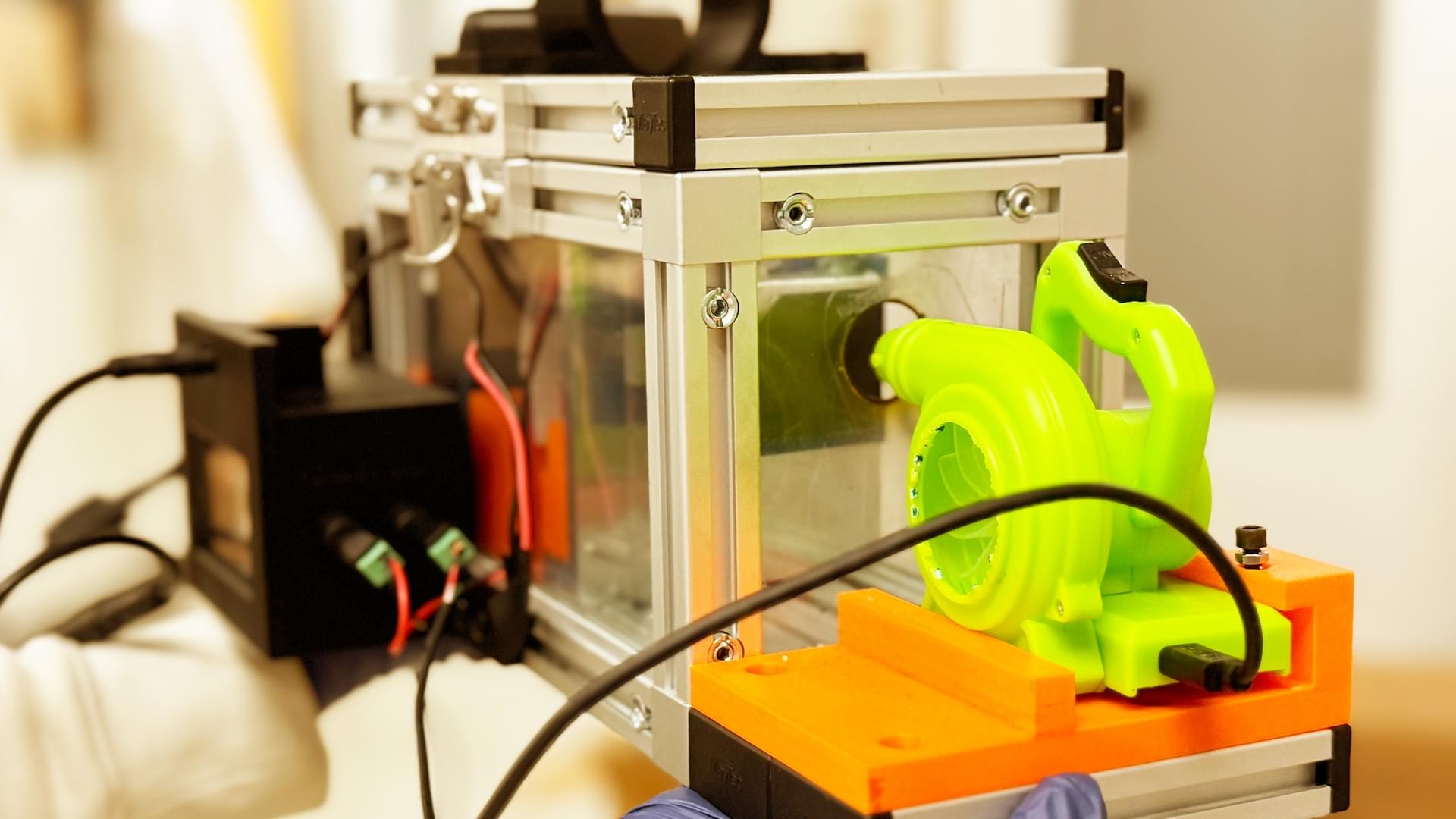

Preparation for the first EXPLORE analog mission planned for June is running on schedule in Austria.

Enthusiasm for our EXPLORE project is contagious, as students and staff at the Amadeus International School in Vienna, Austria will be happy to tell you!

This month teachers in selected schools in Austria, Greece and Portugal received EXPLORE’s physical mission toolkits.

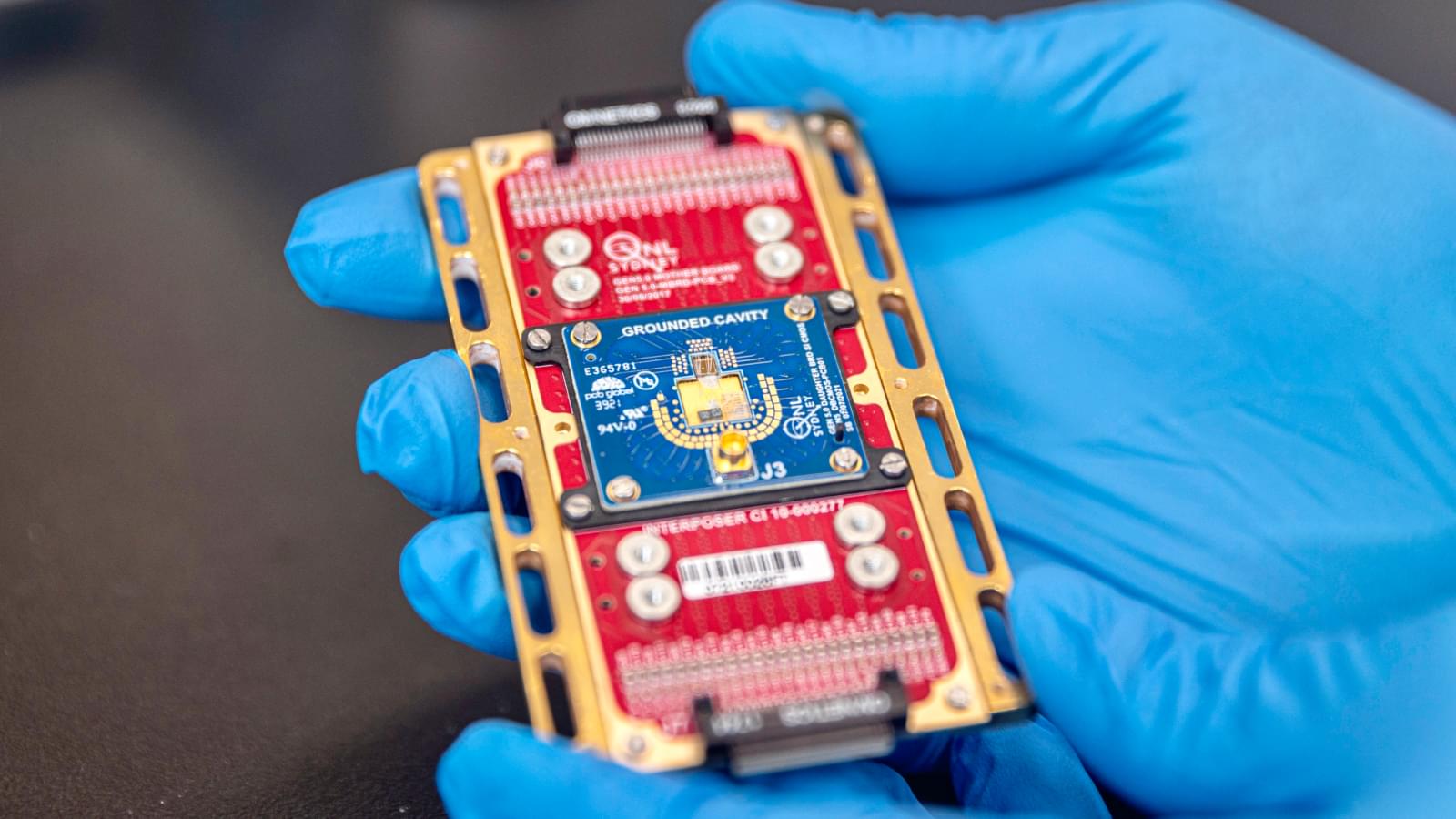

FDA-Approved Pulse Alert & Cryonics Emergency System EventUnlock the next level of biostasis monitoring and cryonics preparedness! Join us for this exclusive…

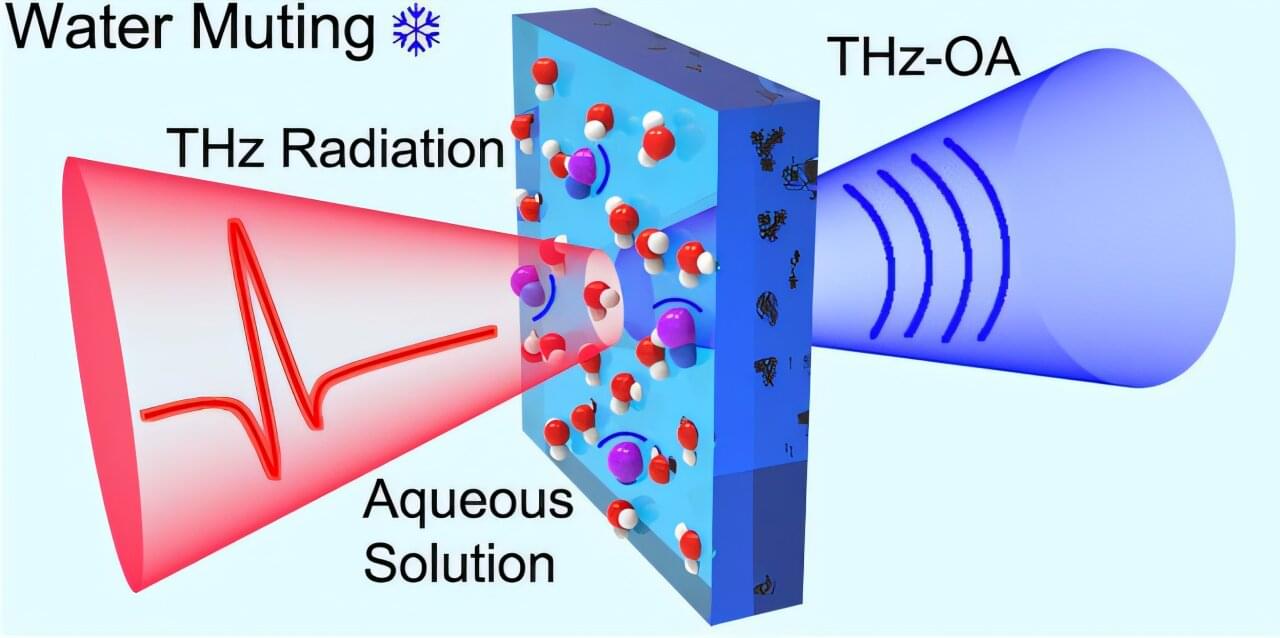

In a new study, researchers demonstrate long-term, non-invasive monitoring of blood sodium levels using a system that combines optoacoustic detection with terahertz spectroscopy. The paper is published in the journal Optica.

Accurate measurement of blood sodium is essential for diagnosing and managing conditions such as dehydration, kidney disease and certain neurological and endocrine disorders.

Terahertz radiation, which falls between microwaves and the mid-infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum, is ideal for biological applications because it is low-energy and non-harmful to tissues, scatters less than near-infrared and visible light and is sensitive to structural and functional biological changes.