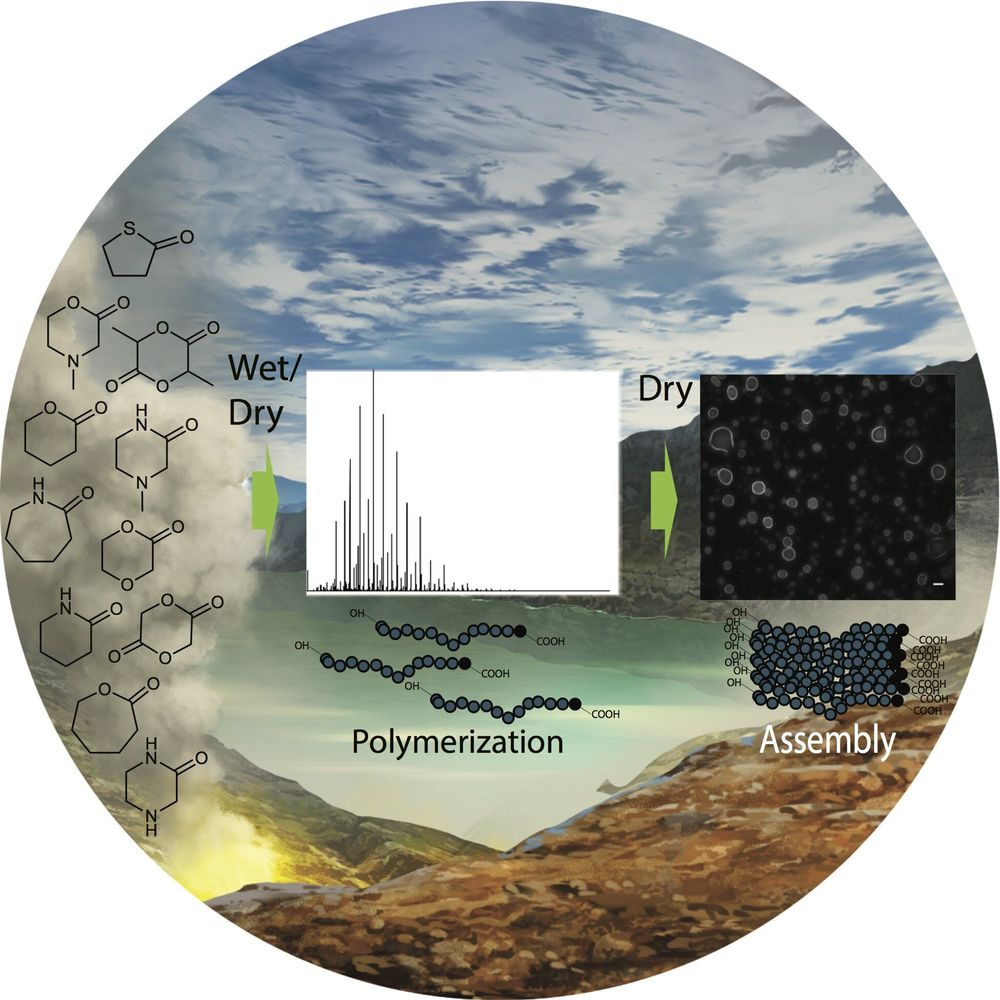

Chemists studying how life started often focus on how modern biopolymers like peptides and nucleic acids contributed, but modern biopolymers don’t form easily without help from living organisms. A possible solution to this paradox is that life started using different components, and many non-biological chemicals were likely abundant in the environment. A new survey conducted by an international team of chemists from the Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI) at Tokyo Institute of Technology and other institutes from Malaysia, the Czech Republic, the U.S. and India, has found that a diverse set of such compounds easily form polymers under primitive environmental conditions, and some even spontaneously form cell-like structures.

Understanding how life started on Earth is one of the most challenging questions modern science seeks to explain. Scientists presently study modern organisms and try to see what aspects of their biochemistry are universal, and thus were probably present in the organisms from which they descended. The best guess is that life has thrived on Earth for at least 3.5 billion of Earth’s 4.5-billion-year history since the planet formed, and most scientists would say life likely began before there is good evidence for its existence. Problematically, since Earth’s surface is dynamic, the earliest traces of life on Earth have not been preserved in the geological record. However, the earliest evidence for life on Earth tells us little about what the earliest organisms were made of, or what was going on inside their cells. “There is clearly a lot left to learn from prebiotic chemistry about how life may have arisen,” says the study’s co-author Jim Cleaves.

A hallmark of life is evolution, and the mechanisms of evolution suggest that common traits can suddenly be displaced by rare and novel mutations which allow mutant organisms to survive better and proliferate, often replacing previously common organisms very rapidly. Paleontological, ecological and laboratory evidence suggests this occurs commonly and quickly. One example is an invasive organism like the dandelion, which was introduced to the Americas from Europe and is now a commo weed causing lawn-concerned homeowners to spend countless hours of effort and dollars to eradicate.