Look at the US Airforce’s new flying car! 😃

The U.S. Air Force has shared images of its newest addition, a flying car, and it doesn’t quite fit the image that’s expected to scare off enemy lines. See for yourself.

Look at the US Airforce’s new flying car! 😃

The U.S. Air Force has shared images of its newest addition, a flying car, and it doesn’t quite fit the image that’s expected to scare off enemy lines. See for yourself.

It looks like they’re replacing news anchors with AI in South Korea.

South Korean cable channel MBN has virtually replicated one of their news anchors with the power of artificial intelligence (AI) technology.

The replacement of lost neurons is a holy grail for neuroscience. A new promising approach is the conversion of glial cells into new neurons. Improving the efficiency of this conversion or reprogramming after brain injury is an important step towards developing reliable regenerative medicine therapies. Researchers at Helmholtz Zentrum München and Ludwig Maximilians University Munich (LMU) have identified a hurdle towards an efficient conversion: the cell metabolism. By expressing neuron-enriched mitochondrial proteins at an early stage of the direct reprogramming process, the researchers achieved a four times higher conversion rate and simultaneously increased the speed of reprogramming.

Neurons (nerve cells) have very important functions in the brain such as information processing. Many brain diseases, injuries and neurodegenerative processes, are characterized by the loss of neurons that are not replaced. Approaches in regenerative medicine therefore aim to reconstitute the neurons by transplantation, stem cell differentiation or direct conversion of endogenous non-neuronal cell types into functional neurons.

Researchers at Helmholtz Zentrum München and LMU are pioneering the field of direct conversion of glial cells into neurons which they have originally discovered. Glia are the most abundant cell type in the brain and can proliferate upon injury. Currently, researchers are able to convert glia cells into neurons — but during the process many cells die. This means that only few glial cells convert into functional nerve cells, making the process inefficient.

While many of us simply flush and forget about it, our pee has the potential to be a valuable resource. As it’s currently managed, though, the world’s pee is not doing us nor the planet a service. That’s why momentum for recycling our own liquid gold is growing: upcycled pee could readily sub in for conventional fertilizers.

Researchers mapping the seafloor off the coast of Tasmania captured the moment a meteor flew through the atmosphere as a fireball and then disintegrated over the ocean.

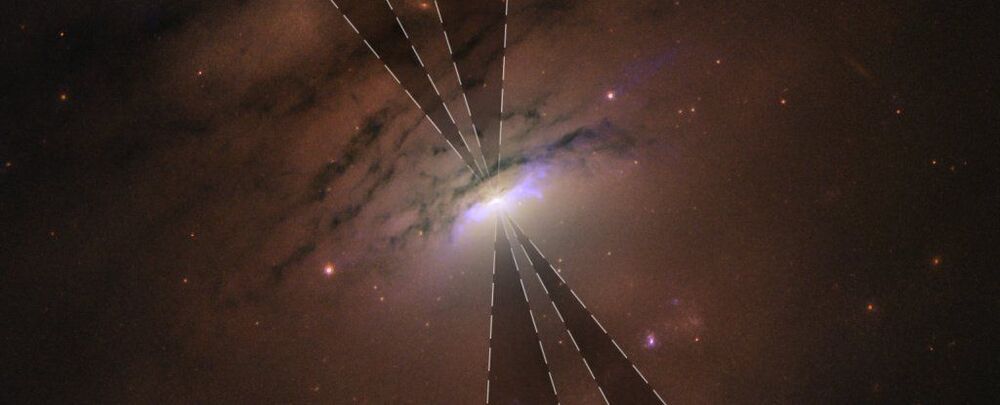

In images from the Hubble Space Telescope, scientists have spotted an entirely new phenomenon. Reaching tens of thousands of light-years into the void of space, vast shadows stretch from the centre of the galaxy IC 5063, as though something is blocking the bright light from therein.

You’ve probably seen something very like it before – bright beams from the Sun when it’s just below the horizon and clouds or mountains only partially block its light, known as crepuscular rays. According to astronomers, the shadows from IC 5063 could be something very similar. They’re just a whole lot bigger – at least 36,000 light-years in each direction.

IC 5063, a galaxy 156 million light-years away, is a Seyfert galaxy. This means it has an active nucleus; the supermassive black hole at its centre is busily guzzling down material from a dense accretion disc and torus of dust and gas around it.

A ‘golden house’ is orbiting Earth! SpaceX launched the unique spacecraft to orbit this morning. It is the Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich ocean observatory, named in honor of former Head of NASA’s Earth Science Division who passed away of cancer in August. The satellite will soon beam the most accurate information of Earth’s oceans which will help meterologists and scientists forecast weather events, like hurricanes, track climate change and rising sea levels. “At NASA, what we do is, we use the vantage point of space to get a global view of the Earth. And in this case, Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich is going to give us a global view of the sea surface height,” Karen St. Germain Director of NASA’s Earth Science Division stated. “The changing Earth processes are affecting sea level globally, but the impact on local communities varies widely. International collaboration is critical to both understanding these changes and informing coastal communities around the world,” she said. Sentinel-6 is a joint project between NASA and the European Aerospace Agency (ESA).

The house-shaped satellite was deployed to orbit atop SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket that lifted off at 9:17 a.m. PST from Space Launch Complex 4E at California’s Vandenberg Air Force Base.