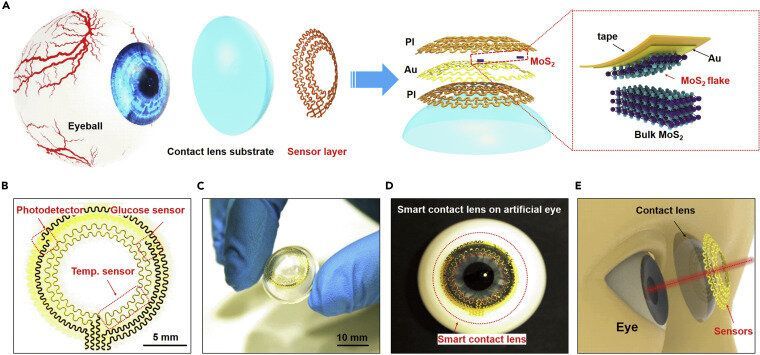

The enormous impact of the recent COVID-19 pandemic, together with other diseases or chronic health risks, has significantly prompted the development and application of bioelectronics and medical devices for real-time monitoring and diagnosing health status. Among all these devices, smart contact lenses attract extensive interests due to their capability of directly monitoring physiological and ambient information. Smart contact lenses equipped with high sensitivity sensors would open the possibility of a non-invasive method to continuously detect biomarkers in tears. They could also be equipped with application-specific integrated circuit chips to further enrich their functionality to obtain, process and transmit physiological properties, manage illnesses and health risks, and finally promote health and wellbeing. Despite significant efforts, previous demonstrations still need multistep integration processes with limited detection sensitivity and mechanical biocompatibility.

Recently, researchers from the University of Surrey, National Physical Laboratory (NPL), Harvard University, University of Science and Technology of China, Zhejiang University Ningbo Research Institute, etc. have developed a multifunctional ultrathin contact lens sensor system. The sensor systems contain a photodetector for receiving optical information, imaging and vision assistance, a temperature sensor for diagnosing potential corneal disease, and a glucose sensor for monitoring glucose level directly from the tear fluid.

Dr. Yunlong Zhao, Lecturer in Energy Storage and Bioelectronics at the Advanced Technology Institute (ATI), University of Surrey and Senior Research Scientist at the UK National Physical Laboratory (NPL), who led this research stated, “These results provide not only a novel and easy-to-make method for manufacturing advanced smart contact lenses but also a novel insight of designing other multifunctional electronics for Internet of Things, human machine interface, etc.” Dr. Zhao added, “our ultrathin transistors-based serpentine mesh sensor system and fabrication strategy allow for further incorporation of other functional components, such as electrode array for electrophysiology, antennas for wireless communication, and the power modules, e.g. thin-film batteries and enzymatic biofuel cell for future in vivo exploration and practical application. Our research team at ATI, University of Surrey and NPL are currently working on these fields.”