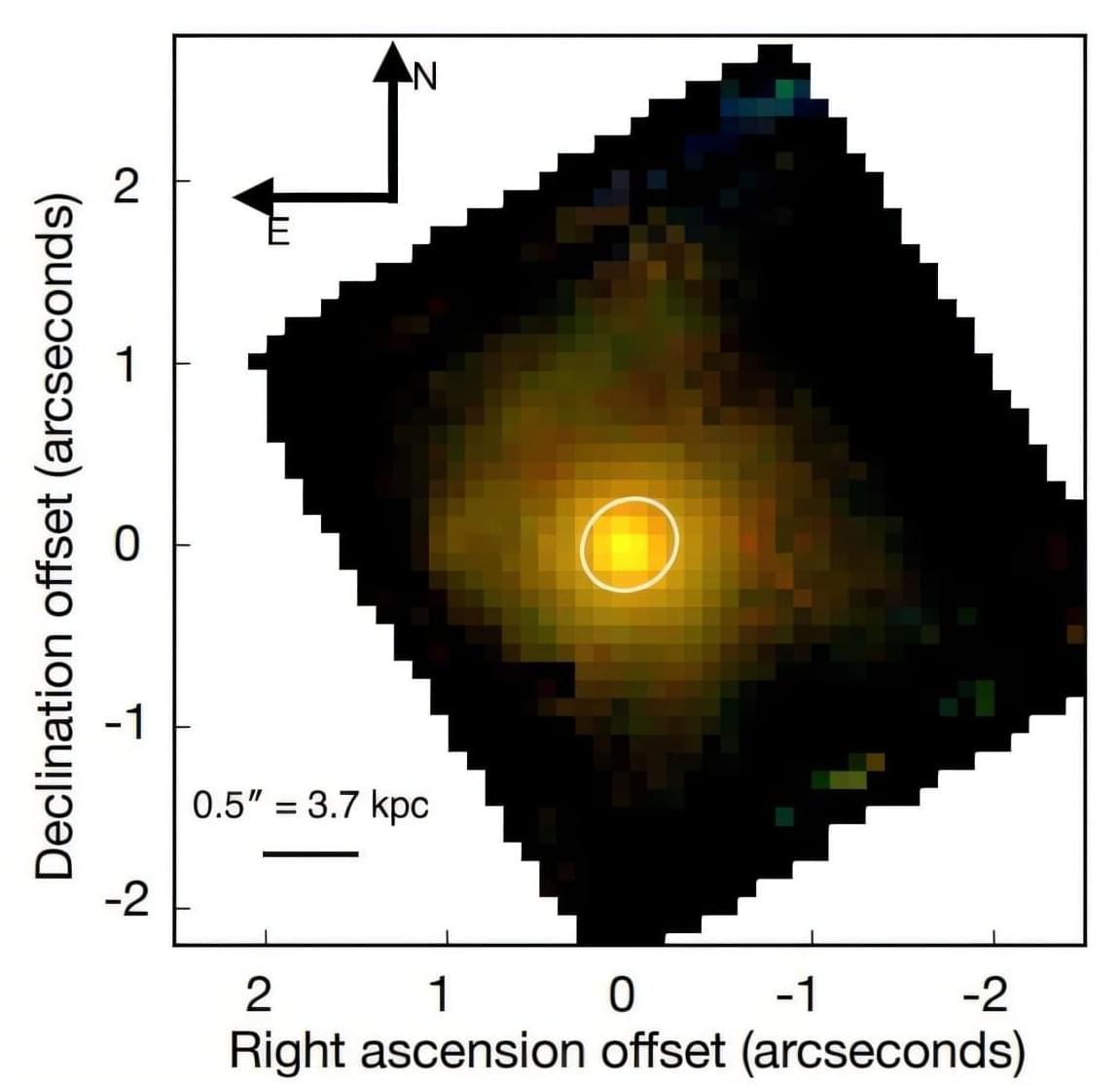

Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers have conducted spectroscopic observations of a high-redshift galaxy known as XMM-VID1-2075. Results of the observational campaign, presented August 14 on the pre-print server arXiv, suggest that XMM-VID1-2075 is a massive and evolved slow-rotator.

The so-called “slow-rotators” represent a small fraction of the most massive galaxies, which stopped forming stars and are dispersion-supported systems. Such galaxies are highly evolved and often exist in dense cluster environments.

To date, no slow-rotators have been confirmed from stellar kinematics beyond the redshift of 2.0. It is generally assumed that at high redshifts, these slow-rotating systems are predicted to be rarely found.