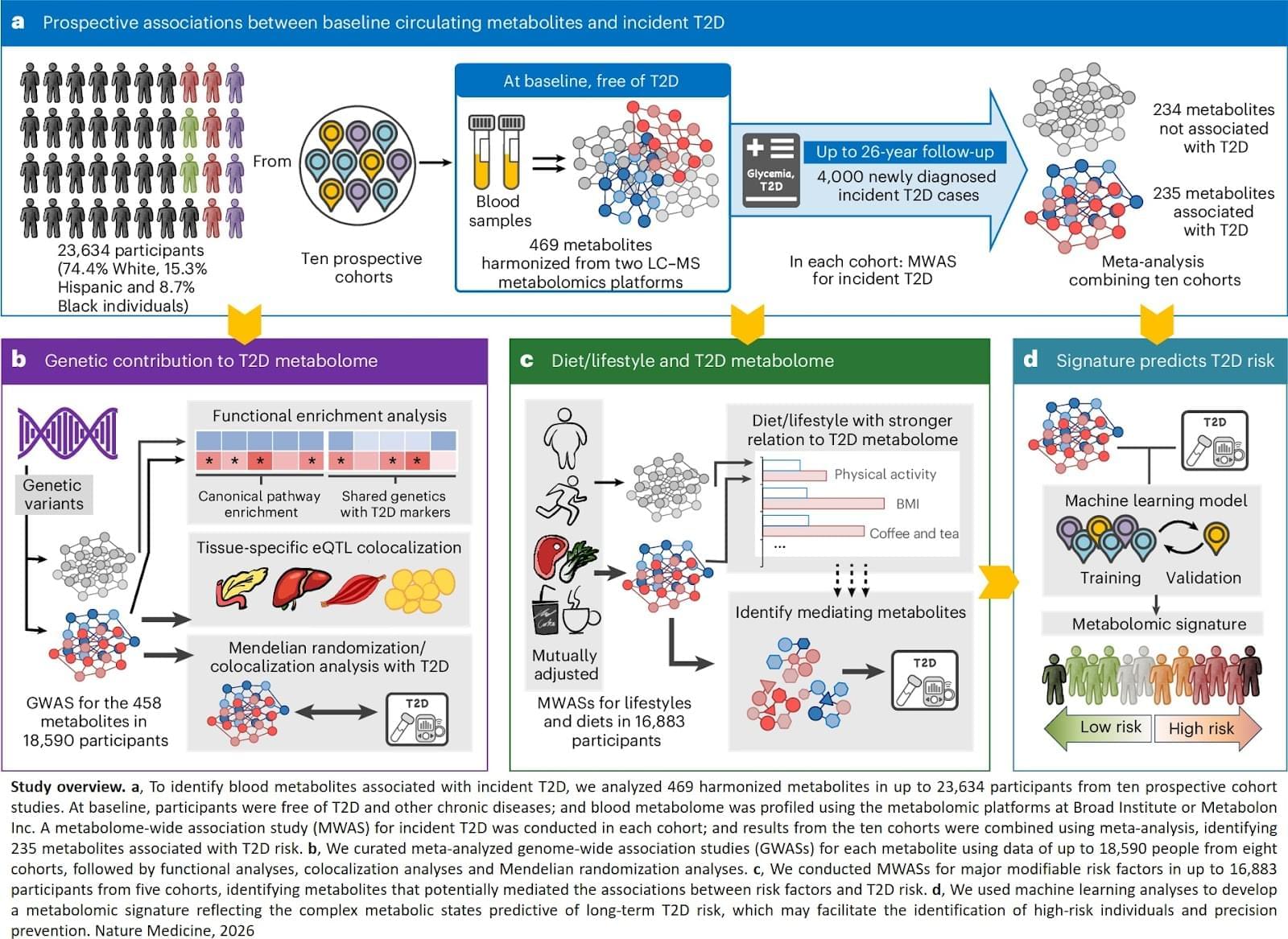

The metabolites associated with type 2 diabetes were also found to be genetically linked to clinical traits and tissue types that are relevant to the disease. Furthermore, the team developed a unique signature of 44 metabolites that improved prediction of future risk of type 2 diabetes. ScienceMission sciencenewshighlights.

Diabetes, a metabolic disease, is on the rise worldwide, and over 90 percent of cases are type 2 diabetes, where the body does not effectively respond to insulin. Researchers identified metabolites (small molecules found in blood generated through metabolism associated with risk of developing type 2 diabetes in the future and revealed genetic and lifestyle factors that may influence these metabolites. They also developed a metabolomic signature that predicts future risk of type 2 diabetes beyond traditional risk factors. Their results are published in Nature Medicine.

In this study, researchers tracked 23,634 individuals with diverse ethnic backgrounds across 10 prospective cohorts with up to 26 years of follow-up. These individuals were initially free of type 2 diabetes. The team analyzed 469 metabolites in blood samples, as well as genetic, diet, and lifestyle data, to see how they relate to risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Of the metabolites examined, 235 were found to be associated with a higher or lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes, 67 of which were new discoveries.

“Interestingly, we found that diet and lifestyle factors may have a stronger influence on metabolites linked to type 2 diabetes than on metabolites not associated with the disease,” said first and co-corresponding author. “This is especially true for obesity, physical activity, and intake of certain foods and beverages such as red meat, vegetables, sugary drinks, and coffee or tea. Increasing evidence suggests that these dietary and lifestyle factors are associated with greater or lower risk of type 2 diabetes. Our study revealed that specific metabolites may act as potential mediators, linking these factors with type 2 diabetes risk.”