“We expected that the hammer of natural selection also comes down randomly, but that is not what we found,” he said. “Rather, it does not act randomly but has a strong bias, favoring those mutations that provide the largest fitness advantage while it smashes down other less beneficial mutations, even though they also provide a benefit to the organism.”

In other words, evolution is not a multitasker when it comes to fixing problems.

“It seems that evolution is myopic,” Venkataram said. “It focuses on the most immediate problem, puts a Band-Aid on and then it moves on to the next problem, without thoroughly finishing the problem it was working on before.”

“It turns out the cells do fix their problems but not in the way we might fix them,” Kaçar added. “In a way, it’s a bit like organizing a delivery truck as it drives down a bumpy road. You can stack and organize only so many boxes at a time before they inevitably get jumbled around. You never really get the chance to make any large, orderly arrangement.”

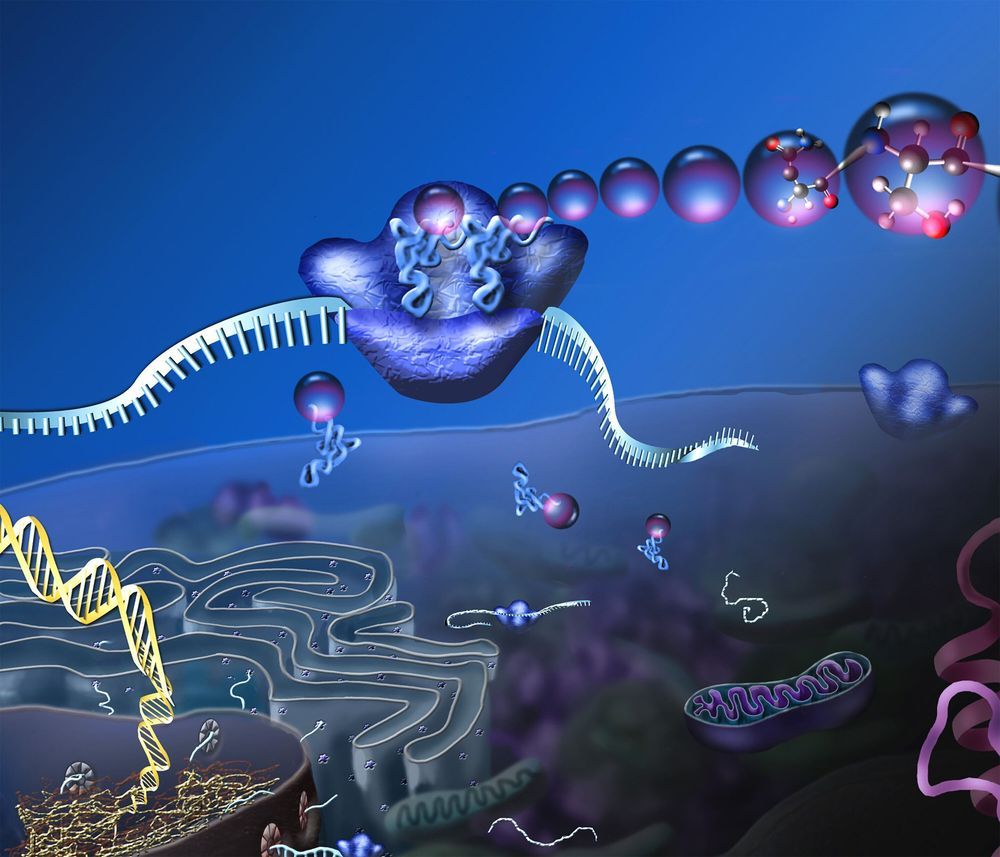

Why natural selection acts in this way remains to be studied, but what the research showed is that, overall, the process results in what the authors call “evolutionary stalling”—while evolution is busy fixing one problem, it does at the expense of all other issues that need fixing. They conclude that at least in rapidly evolving populations, such as bacteria, adaptation in some modules would stall despite the availability of beneficial mutations. This results in a situation in which organisms can never reach a fully optimized state.

“The system has to be capable of being less than optimal so that evolution has something to act on in the face of disturbance—in other words, there needs to be room for improvement,” Kaçar said.

Kaçar believes this feature of evolution may be a signature of any self-organizing system, and she suspects that this principle has counterparts at all levels of biological hierarchy, going back to life’s beginnings, possibly even to prebiotic times when life had not yet materialized.