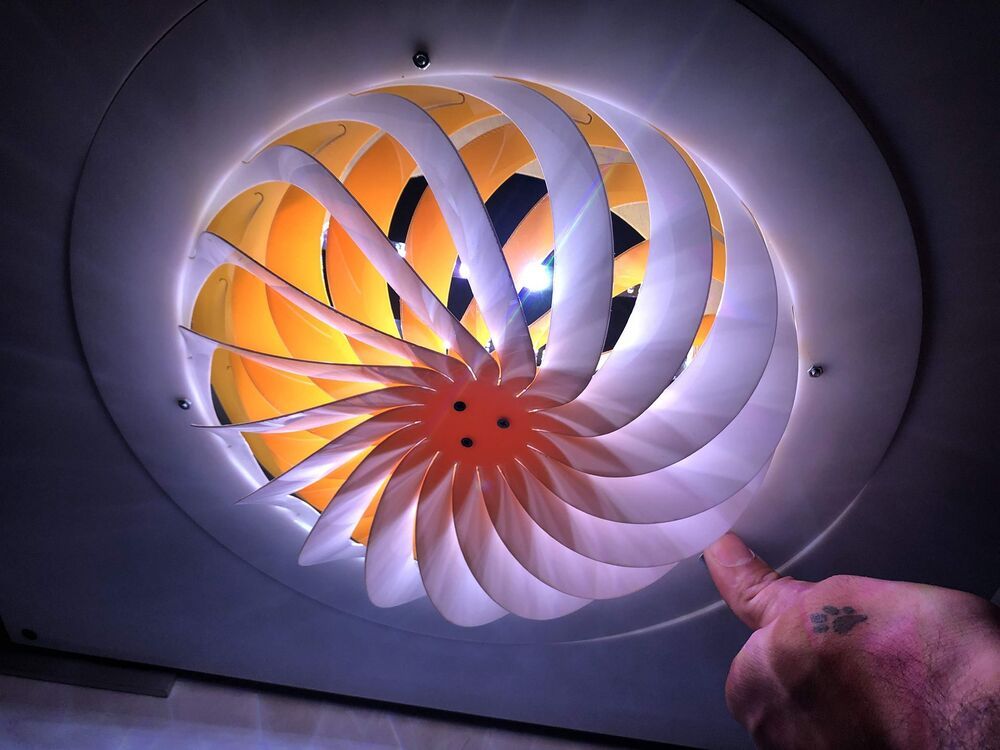

Ordinarily, if you’re building something, you don’t want the materials to buckle under pressure. In a new Harvard University-designed system, however, that buckling action allows flat-packed objects to be twisted into useful three-dimensional forms.

Most existing “buckling-induced deployable structures” consist of linked straight pieces that are popped into shape via straight linear motion, which often requires a fair bit of force to be applied by the user. Folding chairs are one frequently frustrating example.

Seeking an easier alternative, Harvard researchers instead set about building items made up of linked curved pieces. Generally speaking, curved objects (such as beams) are less mechanically stable than their straight counterparts. In most scenarios, this is an undesirable quality. In the case of pop-up devices, though, it means that they’re easier to buckle into the desired form.