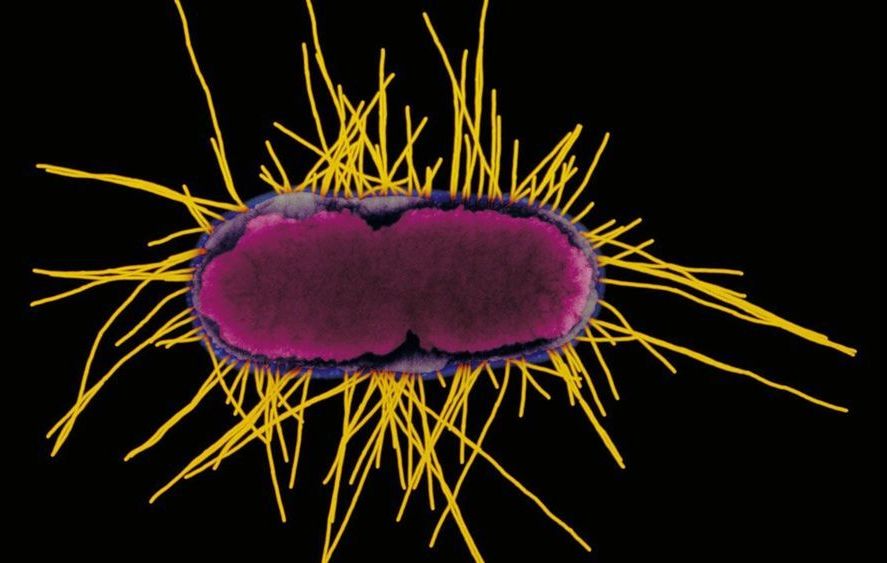

Bacteria, fungi, and viruses can enter our gut through the food we eat. Fortunately, the epithelial cells that line our intestines serve as a robust barrier to prevent these microorganisms from invading the rest of our bodies.

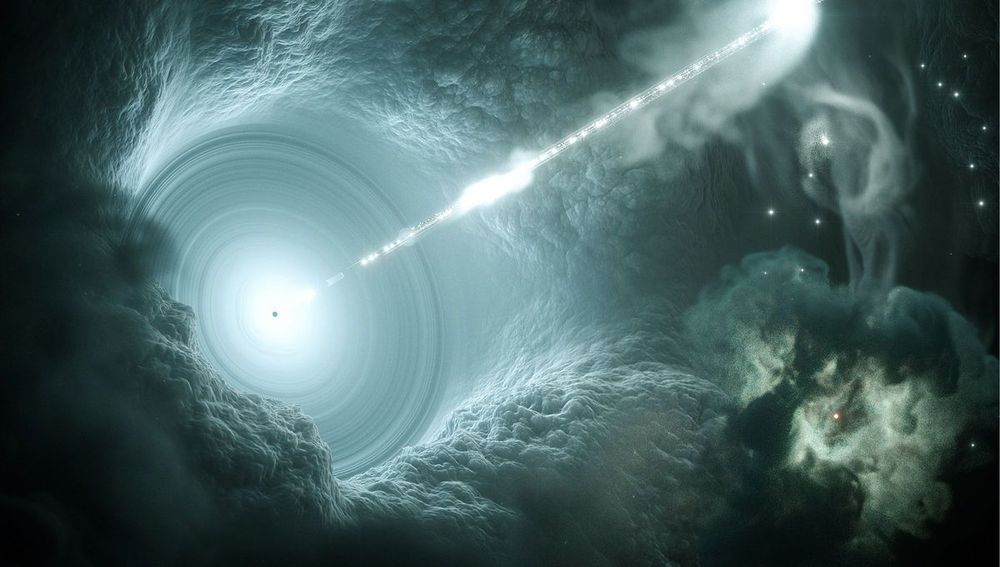

A research team led by a biomedical scientist at the University of California, Riverside, has found that simulated microgravity, such as that encountered in spaceflight, disrupts the functioning of the epithelial barrier even after removal from the microgravity environment.

“Our findings have implications for our understanding of the effects of space travel on intestinal function of astronauts in space, as well as their capability to withstand the effects of agents that compromise intestinal epithelial barrier function following their return to Earth,” said Declan McCole, a professor of biomedical sciences at the UC Riverside School of Medicine, who led the study published today in Scientific Reports.