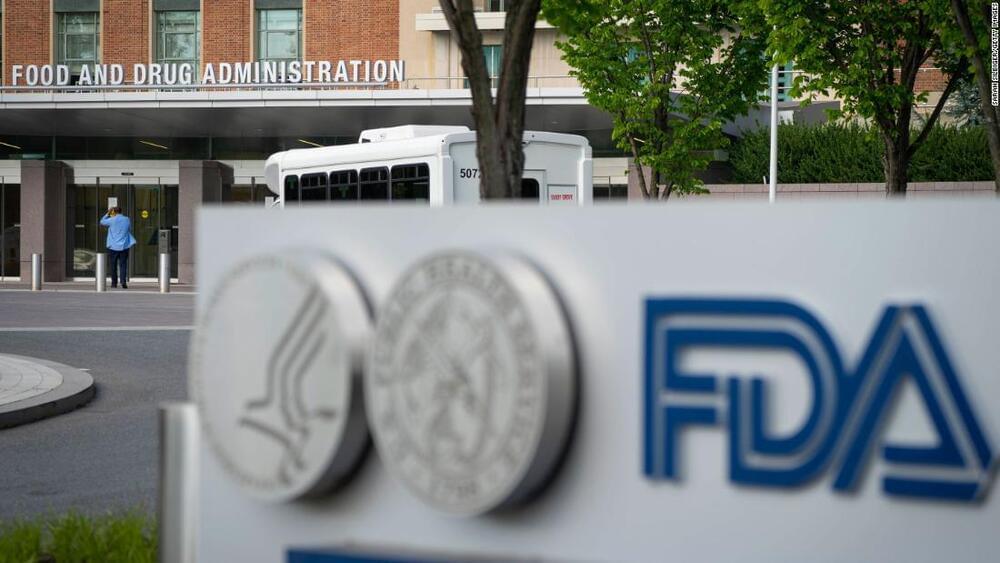

Two senior leaders in the US Food and Drug Administration’s vaccine review office are stepping down, even as the agency works toward high-profile decisions around Covid-19 vaccine approvals, authorizations for younger children and booster shots.

The retirements of Dr. Marion Gruber, director of the Office of Vaccines Research and Review at FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, and Dr. Philip Krause, deputy director of the office, were announced in an internal agency email sent on Tuesday and shared with CNN by the FDA.

In the email, CBER Director Dr. Peter Marks said Gruber will retire on October 31 and Krause is leaving in November. Marks thanked Gruber for her leadership throughout efforts to authorize and approve Covid-19 vaccines, and Krause for serving in a “key role in our interactions to address critical vaccine-related issues with our public health counterparts around the world.”