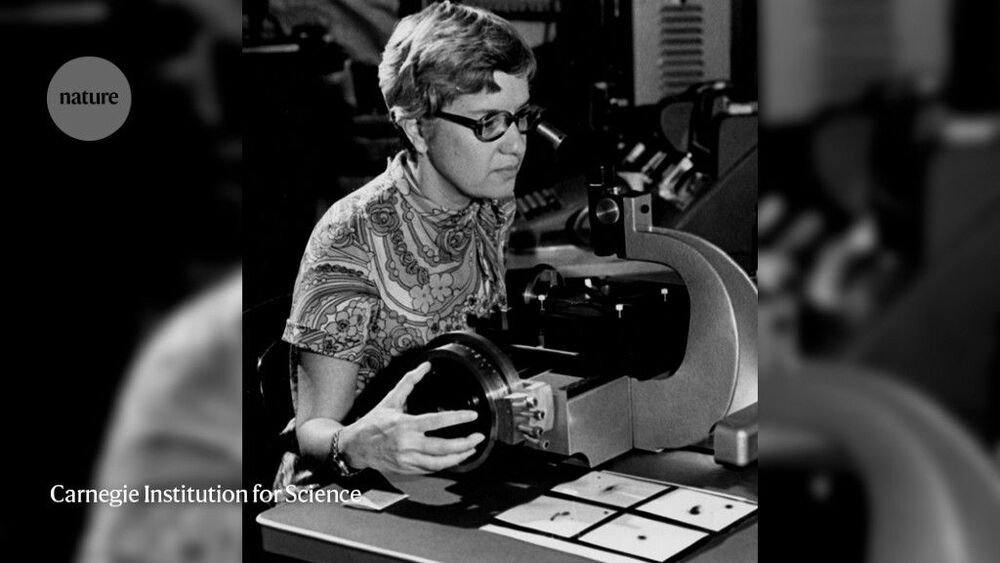

She confirmed dark matter, probed spiral galaxies and fought inequality.

LONDON (AP) — The rainbow flag flew proudly Thursday above the Bank of England in the heart of London’s financial district to commemorate World War II codebreaker Alan Turing, the new face of Britain’s 50-pound note.

The design of the bank note was unveiled before it is being formally issued to the public on June 23, Turing’s birthday. The 50-pound note is the most valuable denomination in circulation but is little used during everyday transactions, especially during the coronavirus pandemic as digital payments increasingly replaced the use of cash.

The new note, which is laden with high-level security features and is made of longer-lasting polymer, completes the bank’s rejig of its paper currencies over the past few years. Turing’s image joins that of Winston Churchill on the five-pound note, novelist Jane Austen on the 10-pound note and artist J. M. W. Turner on the 20-pound note.

“Genius Makers” and “Futureproof,” both by experienced technology reporters now at The New York Times, are part of a rapidly growing literature attempting to make sense of the A.I. hurricane we are living through. These are very different kinds of books — Cade Metz’s is mainly reportorial, about how we got here; Kevin Roose’s is a casual-toned but carefully constructed set of guidelines about where individuals and societies should go next. But each valuably suggests a framework for the right questions to ask now about A.I. and its use.

Two new books — “Genius Makers,” by Cade Metz, and “Futureproof,” by Kevin Roose — examine how artificial intelligence will change humanity.

In response to an independent range test, Tesla has reportedly claimed that the EPA range on its vehicles can be achieved by draining the battery pack beyond the zero-mile displayed range.

Last month, we reported on Edmunds conducting independent range tests on a bunch of electric vehicles to compare them to their EPA estimates.

The results showed that Tesla is using the most optimistic versions of its EPA estimated range in its advertising compared to other automakers.

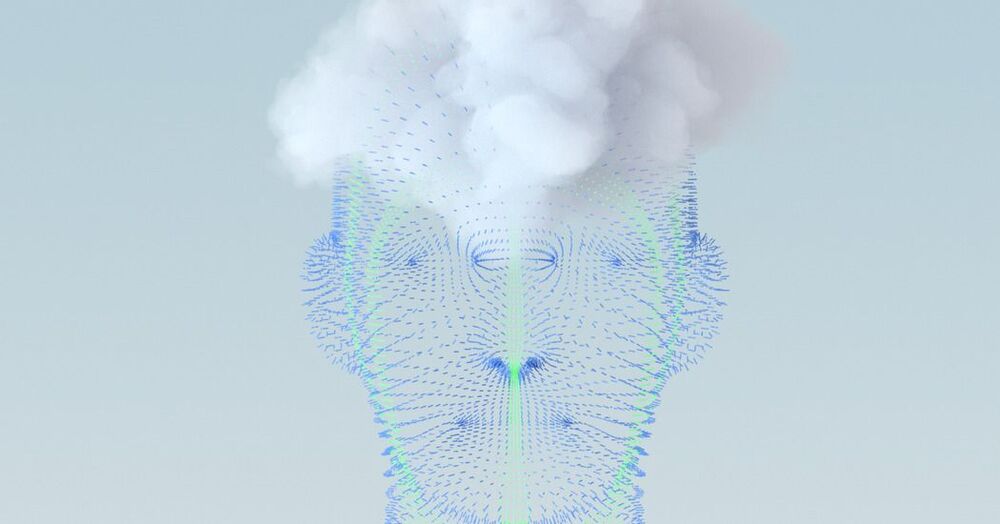

About half of the relatively small portion of the universe that is not dark matter or energy is in fact a mixture of gases that may connect galaxies in a kind of loose cosmic web, according to new research illuminating vast areas that were previously unknown.

Until now, this sizable chunk of “baryonic matter,” which makes up 5% of the universe, had been unaccounted for. Researchers from institutions in Spain and the Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois detailed their findings in a study published March 25 in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

While the other 95% of the universe is made up of dark matter and dark energy, baryonic matter comprises stars, planets, galaxies and everything they contain, including living things. Astronomers knew it was there, but didn’t know if it was more stars, planets or anything else that wasn’t dark matter or energy.

For many Iowans, the first they heard of SpaceX Starlink Internet is when the strange lights started appearing in the night sky in Spring 2020. Long “trains” of dots, each dot being a Starlink satellite.

“There’s all these lights and what looked to me like they were jets,” said John Dunnegan a resident living in rural Des Moines County, Iowa northwest of Burlington. “I thought we were being attacked by Russia. I thought ‘what is that?’ They were all in perfect file. I got on the internet started checking around, and found out what it was. It was Elon Musk’s Starlink.

A proposed flagship in crossover form.

From the moment the Lexus brand made its debut at the North American International Auto Show in Detroit 29 years ago, the LS sedan has been the division’s flagship. But the luxury segment, just like the rest of the automobile market, increasingly is turning away from sedans and toward crossovers. So Lexus is testing the waters for what it dubs “a new flagship luxury crossover” with the debut of the LF-1 Limitless concept at this year’s Detroit auto show.

A huge container ship blocking the Suez Canal like a “beached whale” may take weeks to free, the salvage company said, as officials stopped all ships entering the channel on Thursday in a new setback for global trade. The 400 metre Ever Given, almost as long as the Empire State Building is high, is blocking transit in both directions through one of the world’s busiest shipping channels for oil and refined fuels, grain and other trade linking Asia and Europe. The Suez Canal Authority (SCA) said earlier that nine tugs were working to move the vessel, which got stuck diagonally across the single-lane southern stretch of the canal on Tuesday morning amid high winds and a dust storm.