Immunotherapy is an increasingly powerful form of cancer treatment where the patient’s own immune system is equipped with heightened abilities to take down the disease, and one promising arm of this is known as adoptive cell therapy. This involves using altered versions of a patient’s own cells to trigger a more strong-handed response from their own immune system. Scientists at Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center are reporting an exciting advance in this area, demonstrating that engineered bone marrow cells can slow the growth of prostate and pancreatic cancers in mice.

The study builds on previous research where scientists demonstrated that a range of cancers, including melanomas, colon cancer and brain cancer, grow much more slowly in mice that are lacking a certain gene, known as p50, which seems to activate a stronger immune response. The Johns Hopkins researchers sought to further validate these earlier findings, while expanding the utility of a promising form of cancer therapy.

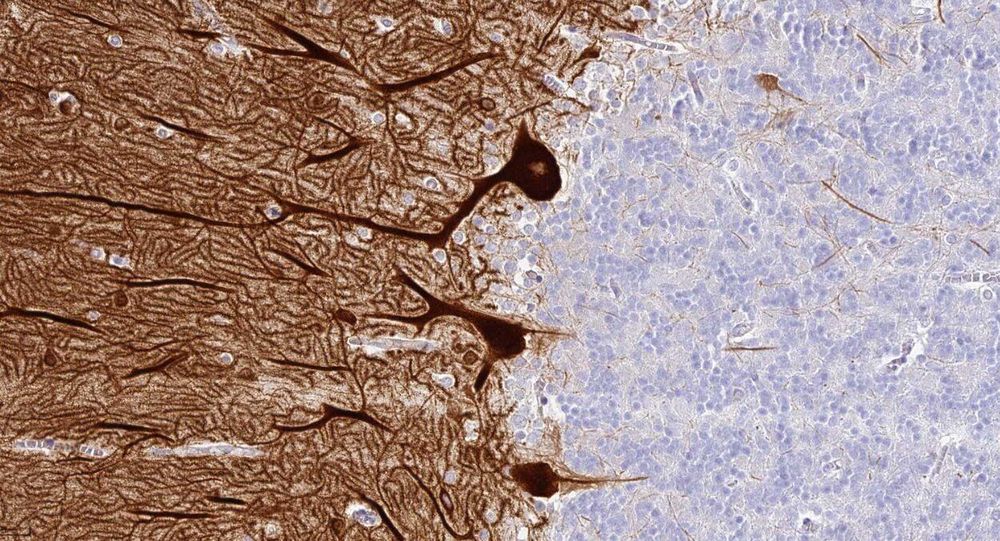

To do this, the team worked with what are known as immature myeloid cells, a type of white blood cell, which previous research had indicated could help switch on immune responses that fight tumors. In this case, the immature myeloid cells were taken from the bone marrow of mice engineered to lack the p50 gene, as a way of comparing them to the behavior of cells taken from mice who had the p50 gene in tact.