Multiple vulnerabilities have been disclosed in Hitachi Vantara’s Pentaho Business Analytics software.

But in recent years the government has signaled its intent to open up the sector to private players and last year passed a series of reforms designed to foster innovation and encourage new start ups. Earlier this month Prime Minister Narendra Modi also launched the Indian Space Association, an industry body designed to foster collaboration between public and private players.

One of the companies that has been quick to pounce on these new opportunities is Agnikul, which is being incubated at the Indian Institute of Technology Madras in Chennai. This February, the company successfully test fired its 3D-printed Agnilet rocket engine, just four years after its founding.

While other private space companies like Relativity Space and Rocket Lab also use 3D printing to build their rockets, Agnikul is the first to print an entire rocket engine as a single piece. IEEE Spectrum spoke to co-founder and chief operating officer Moin SPM to find out why the company thinks this gives them an edge in the burgeoning “launch on-demand” market for small satellites. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

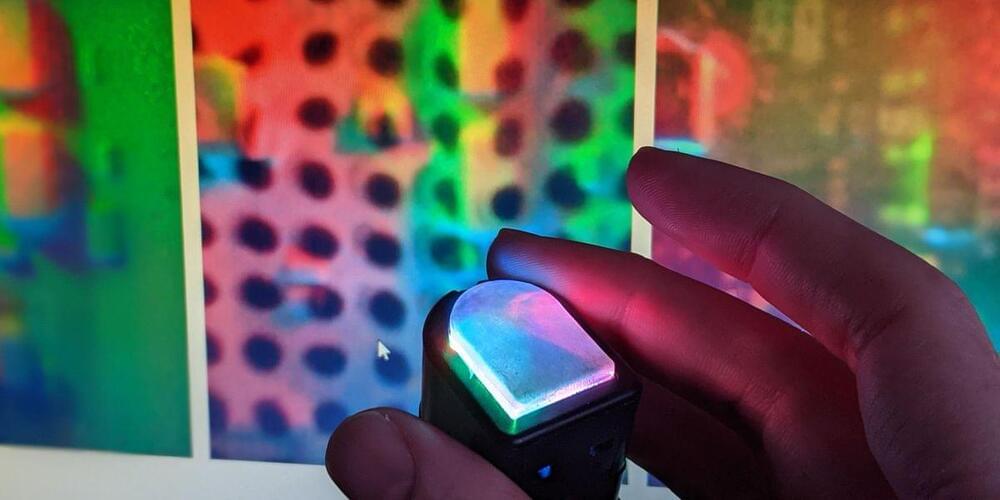

A team of physicists has discovered how DNA molecules self-organize into adhesive patches between particles in response to assembly instructions. Its findings offer a “proof of concept” for an innovative way to produce materials with a well-defined connectivity between the particles.

The work is reported in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“We show that one can program particles to make tailored structures with customized properties,” explains Jasna Brujic, a professor in New York University’s Department of Physics and one of the researchers. “While cranes, drills, and hammers must be controlled by humans in constructing buildings, this work reveals how one can use physics to make smart materials that ‘know’ how to assemble themselves.”

The device you are currently reading this article on was born from the silicon revolution. To build modern electrical circuits, researchers control silicon’s current-conducting capabilities via doping, which is a process that introduces either negatively charged electrons or positively charged “holes” where electrons used to be. This allows the flow of electricity to be controlled and for silicon involves injecting other atomic elements that can adjust electrons—known as dopants—into its three-dimensional (3D) atomic lattice.

Silicon’s 3D lattice, however, is too big for next-generation electronics, which include ultra-thin transistors, new devices for optical communication, and flexible bio-sensors that can be worn or implanted in the human body. To slim things down, researchers are experimenting with materials no thicker than a single sheet of atoms, such as graphene. But the tried-and-true method for doping 3D silicon doesn’t work with 2D graphene, which consists of a single layer of carbon atoms that doesn’t normally conduct a current.

Rather than injecting dopants, researchers have tried layering on a “charge-transfer layer” intended to add or pull away electrons from the graphene. However, previous methods used “dirty” materials in their charge-transfer layers; impurities in these would leave the graphene unevenly doped and impede its ability to conduct electricity.

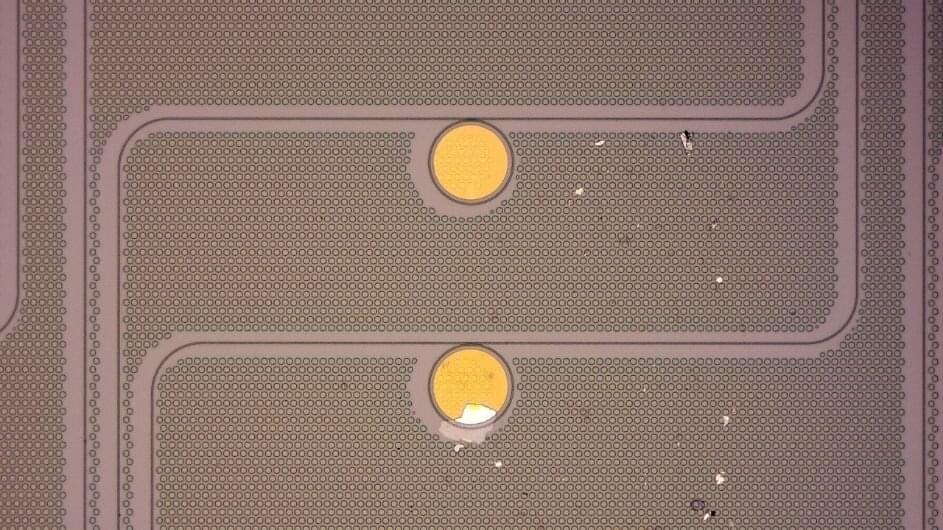

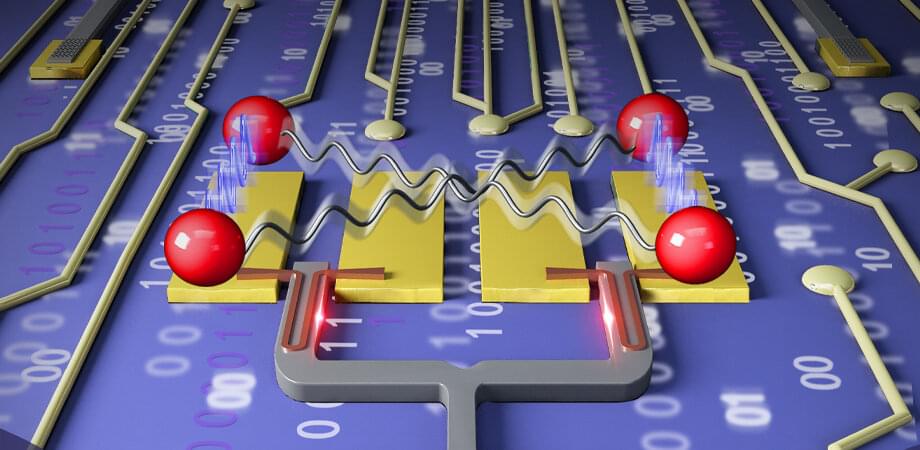

Integrated quantum photonics (IQP) is a promising platform for realizing scalable and practical quantum information processing. Up to now, most of the demonstrations with IQP focus on improving the stability, quality, and complexity of experiments for traditional platforms based on bulk and fiber optical elements. A more demanding question is: “Are there experiments possible with IQP that are impossible with traditional technology?”

This question is answered affirmatively by a team led jointly by Xiao-Song Ma and Labao Zhang from Nanjing University, and Xinlun Cai from Sun Yat-sen University, China. As reported in Advanced Photonics, the team realizes quantum communication using a chip based on silicon photonics with a superconducting nanowire single-photon detector (SNSPD). The excellent performance of this chip allows them to realize optimal time-bin Bell state measurement and to significantly enhance the key rate in quantum communication.

The single photon detector is a key element for quantum key distribution (QKD) and highly desirable for photonic chip integration to realize practical and scalable quantum networks. By harnessing the unique high-speed feature of the optical waveguide-integrated SNSPD, the dead time of single-photon detection is reduced by more than an order of magnitude compared to the traditional normal-incidence SNSPD. This in turn allows the team to resolve one of the long-standing challenges in quantum optics: Optimal Bell-state measurement of time-bin encoded qubits.

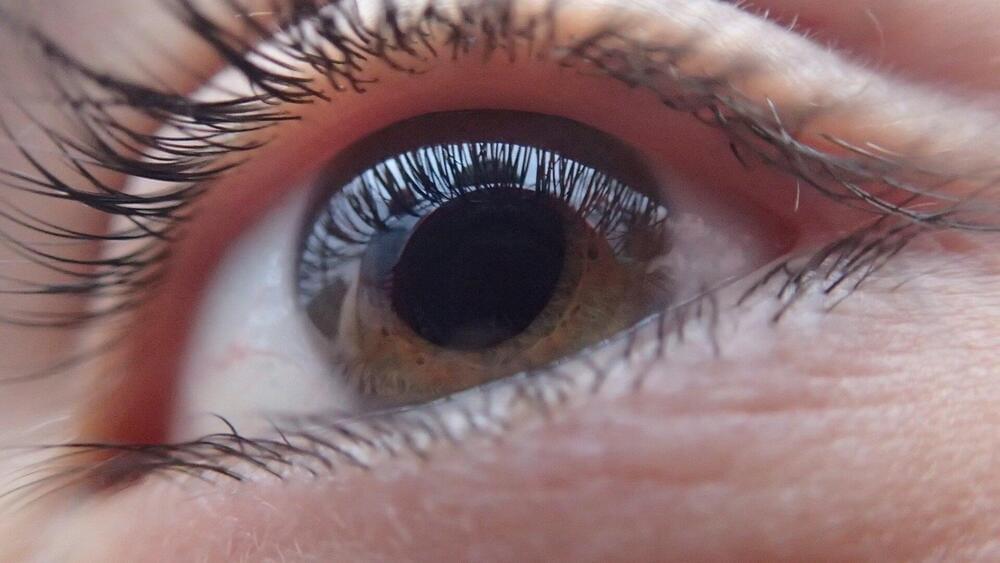

Scientists at the John A. Moran Eye Center at the University of Utah have discovered a new type of nerve cell, or neuron, in the retina.

In the central nervous system, a complex circuitry of neurons communicate with each other to relay sensory and motor information; so-called interneurons serve as intermediaries in the chain of communication. Publishing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, a research team led by Ning Tian, Ph.D., identifies a previously unknown type of interneuron in the mammalian retina.

The discovery marks a notable development for the field as scientists work toward a better understanding of the central nervous system by identifying all classes of neurons and their connections.

Two drugs approved decades ago not only counteract brain damage caused by Alzheimer’s disease in animal models, the same therapeutic combination may also improve cognition.

Sounds like a slam dunk in terms of a cure—but not yet. Researchers currently are concentrating on animal studies amid implications that remain explosive: If a surprising drug combination continues to destroy a key feature of the disease, then an effective treatment for Alzheimer’s may have been hiding for decades in plain sight.

A promising series of early studies is highlighting two well known medicine cabinet standbys—gemfibrosil, an old-school cholesterol-lowering drug, and retinoic acid, a vitamin A derivative. Gemfibrosil, is sold as Lopid and while it’s still used, it is not widely prescribed. Doctors now prefer to prescribe statins to lower cholesterol. Retinoic acid has been used in various formulations to treat everything from acne to psoriasis to cancer.