The journey to see future technology starts in 2022, when Elon Musk and SpaceX send the first Starship to Mars — beginning the preparations for the arrival of the first human explorers.

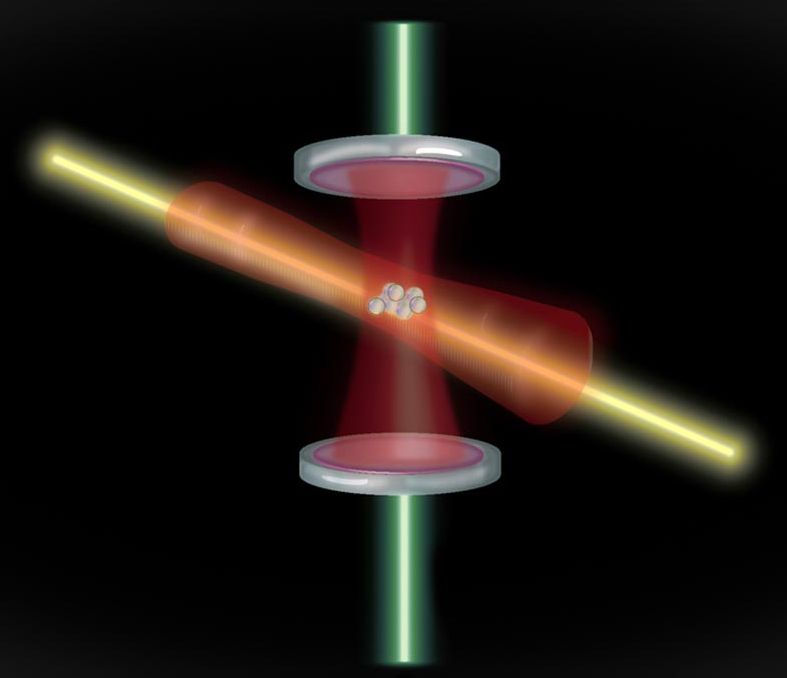

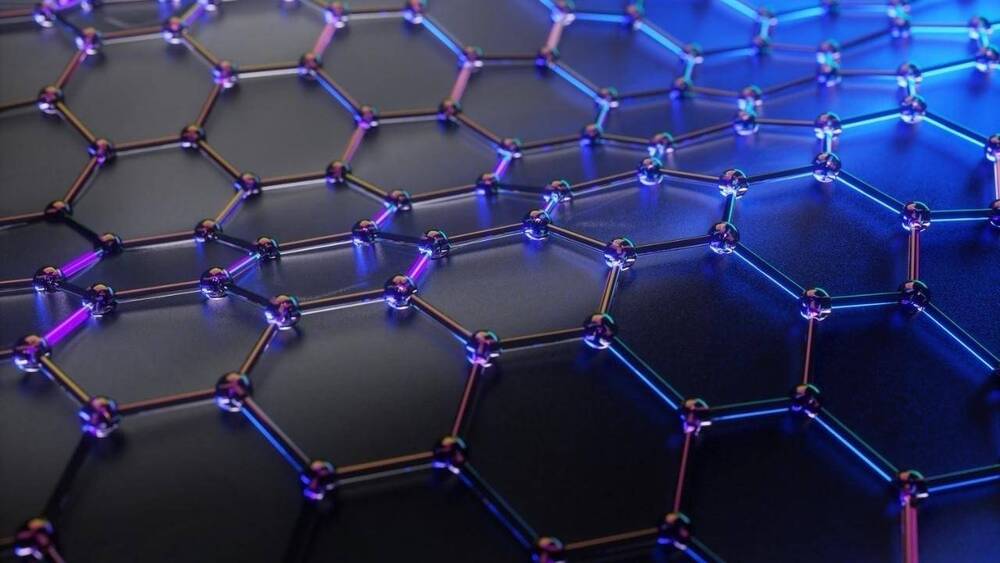

We see the evolution of space exploration, from NASA’s Artemis mission, humans landing on Mars, and the interplanetary internet system going online. To the launch of the Starshot Alpha Centauri program, and quantum computers designing plants that can survive on Mars.

On Earth, tech evolves with quantum computers and Neaulink chips. People begin living with bio-printed organs. Humans record every part of lives from birth. And inner speech recording becomes possible.

And what about predictions further out into the future, when humans become level 2 and level 3 civilizations. When NASA’s warp drive goes live, and Mars declares independence from Earth. Will there be Dyson structures built around stars to capture their energy. Will they help power computers that can take human consciousness and download it into a quantum computer core. Allowing humanity to travel further out into space.

Quotes about the future from: Arthur C. Clarke, Stephen Hawking, Albert Einstein, and Elon Musk.

Additional footage sourced from: NASA, SpaceX.