A new machine learning model shows that star-shaped brain cells may be responsible for the brain’s memory capacity, and someday, it could inspire advances in AI and Alzheimer’s research.

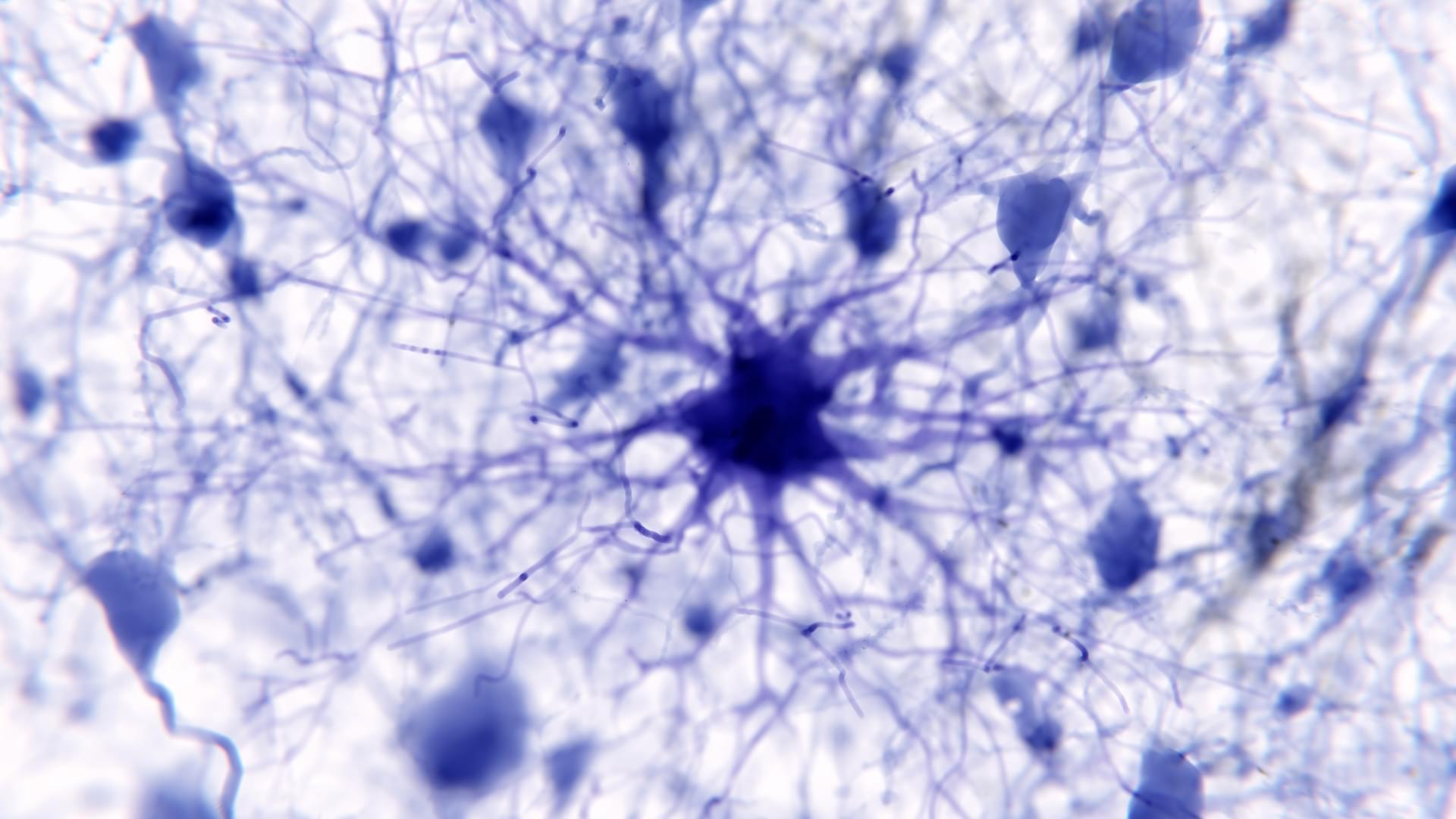

Xanadu has achieved a significant milestone in the development of scalable quantum hardware by generating error-resistant photonic qubits on an integrated chip platform. A foundational result in Xanadu’s roadmap, this first-ever demonstration of such qubits on a chip is published in Nature.

This advance builds on Xanadu’s recent announcement of the Aurora system, which demonstrated—for the first time—all key components required to build a modular, networked, and scalable photonic quantum computer. With this latest demonstration of robust qubit generation using silicon-based photonic chips, Xanadu further strengthens the scalability pillar of its architecture.

The quantum states produced in this experiment, known as Gottesman–Kitaev–Preskill (GKP) states, consist of superpositions of many photons to encode information in an error-resistant manner—an essential requirement for future fault-tolerant quantum computers. These states allow logic operations to be performed using deterministic, room-temperature-compatible techniques, and they are uniquely well-suited for networking across chips using standard fiber connections.

Some autistic traits related to challenges with social interaction, mental flexibility and visual perception could be alleviated through a new, noninvasive therapy. A team of researchers, including those from the University of Tokyo, found that stimulating nerve cells when the brain becomes “stuck” in a certain state improves flexibility and relieves some autistic behaviors. The procedure utilized transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), which is already used to treat certain mood disorders, in a novel manner.

The study is published in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

Over 40 adults with a mild form of autism participated, and the therapeutic effects lasted for up to two months after the last session. This study could contribute toward projects enabling new treatments.

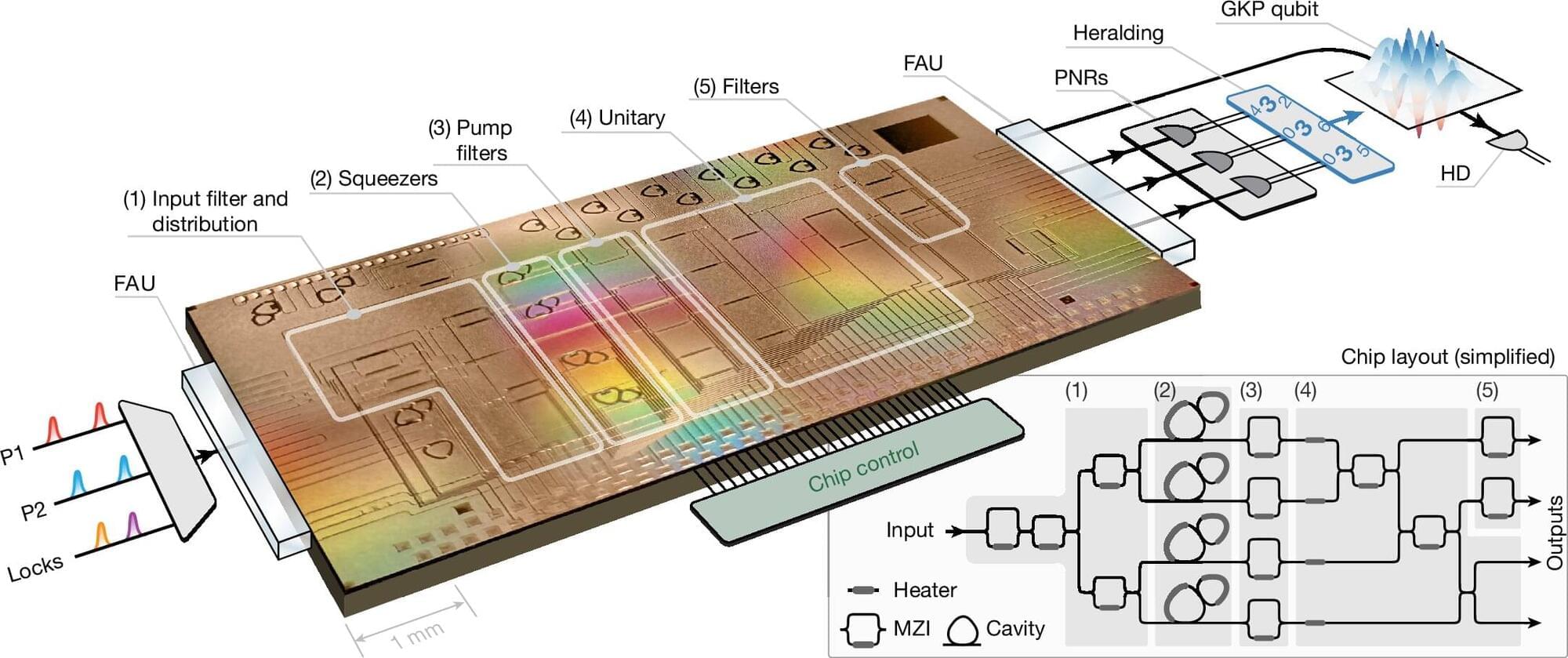

Serotonin signaling and gut-immune crosstalk: the microbiome’s role in antitumor immunity.

“…Serotonin transporter inhibits cytotoxic CD8-positive T lymphocyte antitumor immunity by depleting serotonin within the tumor microenvironment…”

“…Serotonin transporter-blocking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants enhance cytotoxic CD8-positive T lymphocyte antitumor immunity and act synergistically with programmed cell death protein 1 immune checkpoint blockade therapy…”

To this end, here…

“…Tumor-infiltrating cytotoxic CD8-positive T lymphocytes were identified as the primary producers and mediators of a local, immunomodulatory serotonin signaling pathway independent of the gastrointestinal tract…”

“…Upon recognition of tumor antigens, tumor-infiltrating cytotoxic CD8-positive T lymphocytes upregulate tryptophan hydroxylase 1, which synthesizes serotonin followed by its release into the tumor microenvironment to enhance T lymphocyte activation via serotonin signaling…”

In short…

At Phobio, well-implemented AI hasn’t just made us faster—it’s made us sharper, more creative and more strategic. When routine tasks are streamlined, people have time to think deeply about customers, competition and innovation.

Closing Thoughts

AI isn’t coming to take your job. But someone who knows how to use it might.

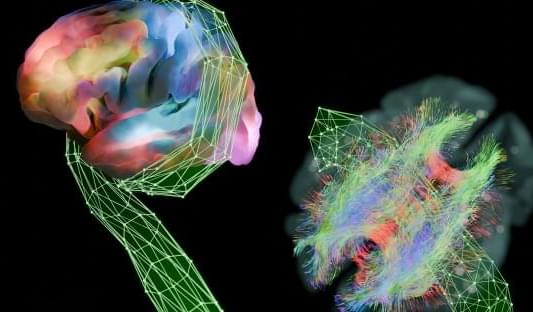

Using an algorithm they call the Krakencoder, researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine are a step closer to unraveling how the brain’s wiring supports the way we think and act. The study, published June 5 in Nature Methods, used imaging data from the Human Connectome Project to align neural activity with its underlying circuitry.

Mapping how the brain’s anatomical connections and activity patterns relate to behavior is crucial not only for understanding how the brain works generally but also for identifying biomarkers of disease, predicting outcomes in neurological disorders and designing personalized interventions.

The brain consists of a complex network of interconnected neurons whose collective activity drives our behavior. The structural connectome represents the physical wiring of the brain, the map of how different regions are anatomically connected.

Get ready for GENIUS… I’m with STARGATE Genius! Join me and Dominic Dirkx, aeropspace engineer and assistant professor at @tudelft as we discuss distant m…