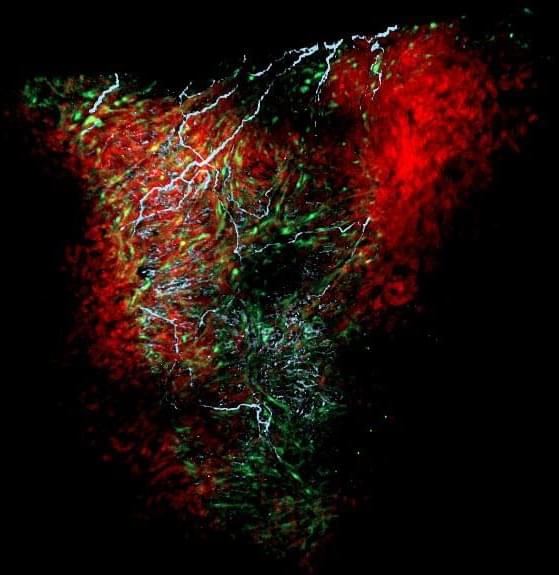

Discovery suggests glial cells may be important in other organs as well.

Glial cells in the heart help regulate heart rate and rhythm, and drive its development in the embryo, according to a new study publishing today (November 18th, 2021) in the open-access journal PLOS Biology by Nina Kikel-Coury, Cody Smith and colleagues at the University of Notre Dame. The discovery provides the most detailed portrait yet of a critical population of cells that had been previously poorly understood.

Glia are a diverse set of cell types, originally named after the Greek word for glue, and include cells that surround and nourish neurons, and others that mount immune responses within the central nervous system. In the peripheral nervous system, glia are present and presumably active in multiple organs, including the gut, pancreas, spleen, and lungs, although their function is not clear in most cases.